To celebrate Hoodline's new Castro connection, we're taking a closer look at the literal union between our neighborhoods: where Divisadero Street turns into Castro Street.

It wasn't always this way. If you look at a map from the turn of the 20th century, you'll notice that Divisadero (at the time called "Devisadero"), just... ends.

The story of how the two streets joined isn't just about a little neighborhood paving, though. It's an early chapter in the development of the city's freeways, the Freeway Revolts of the 1950s and 60s, and the ongoing debates about transit and city planning today.

Divisadero and Castro, 1904:

(Image: David Rumsey)

Divisadero and Castro, 2014:

(Image: Google)

Most of the Western Addition and Castro neighborhoods were spared destruction from the 1906 earthquake, and prospered in the next couple of decades. Meanwhile, by the 1930s, cars had become common on local streets. Traffic was getting snarled, and the city was trying to figure out what to do.

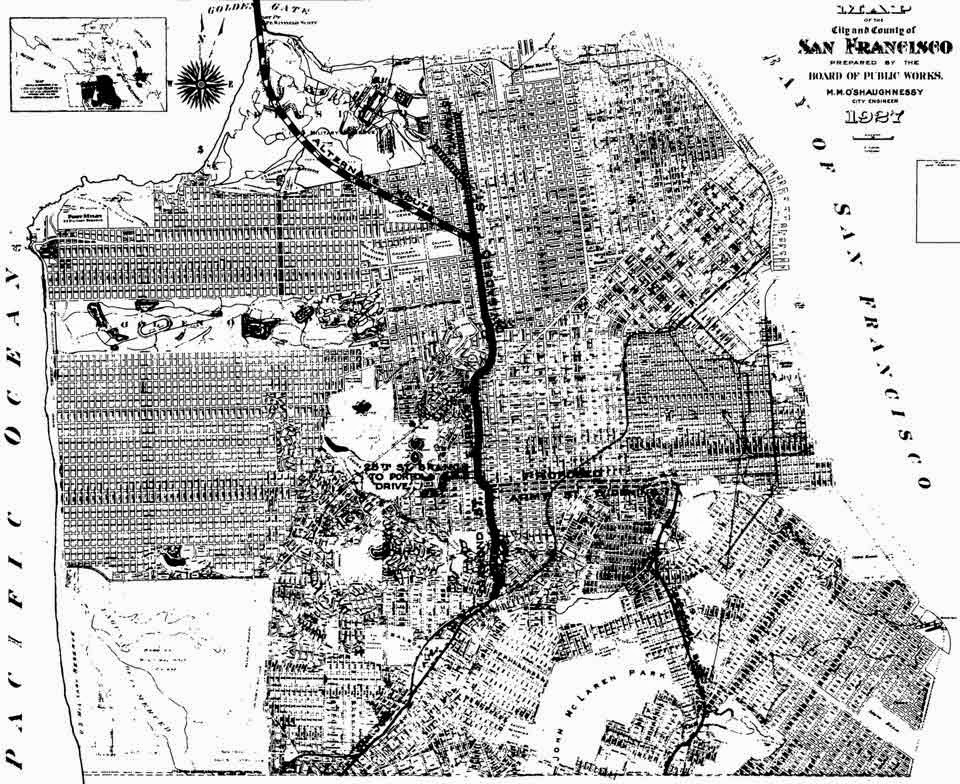

A leading idea was to build a "Castro-Divisadero Divisional Highway" up the middle of the city, from Alemany Boulevard to Lombard Street, where it would connect with the proposed Golden Gate Bridge. The concept first seems to have surfaced in the 1920s, based on our research in the archives of the San Francisco Public Library. Here's a proposed map from 1927, via Walking SF:

The route was staunchly supported by the Eureka Valley Promotion Association, a local neighborhood group found in 1881. It represented the Castro area, and saw the highway as a new way to ease local traffic and help get more customers to area businesses.

Remember, this was decades before the federal highway system, back when today's 101 was still a section of Bayshore Boulevard, and before the Central Freeway gave cars direct access to the middle of the city.

If you look through the EVPA meeting minutes from the late 20s and early 30s, you'll find a long-running set of discussions about the highway's progress, supporting the Castro-Divisadero connection at the most local level, the broader Alemany-to-Lombard highway concept, and the notion of the Golden Gate Bridge itself.

At one meeting in late 1929, “Congressman [Richard J.] Welch reported that the proposed Cross Town Divisional Highway and Golden Gate Bridge were badly need by San Francisco, but stressed the necessity of making the highway wide enough to accommodate future traffic. The association went on record as declaring the Golden Gate Bridge a vital need of San Francisco.”

Although few may realize this now, the bridge was a controversial project at the time, and its supporters had to fight hard to raise the bond money needed for it.

But the EVPA could not be put off from the local highway concept. In a 1932 meeting, the year before Bay Area voters approved Bridge funding, member and city engineer George S. Hill told his colleagues that "we should not wait for the favorable dicisdion [sic] on the Golden Gate Bridge as the Divisional Highway is necessary whether the bridge is built or not."

Working closely with the Castro Improvement Club (another neighborhood group), the EVPA raised money and rallied political support – with the priority being the Castro-Divisadero street connection.

By 1934 the city had purchased $50,000 worth of lots in the Castro and Divisadero area with the intention of buying up $55,000 more to clear for a new cross-city highway. Another $70,000 was budgeted for construction purposes, such as widening the road to 60'. Plans were put into place to reroute cable cars to side roads, and a tunnel was planned in the northern Marina-end of Divisadero to expedite traffic to the bridge. (Calculated for inflation, this adds up to around $3 million in 2014 dollars.)

Writing in a 1938 edition of Architect & Engineer, Hill praised the plan he had been supporting for years.

"The evolution of a network of major streets is the key to the solution of the transportation and traffic problems in San Francisco... San Francisco is a city of many hills and valleys which should be made accessible not only from the business center but from one another. Only in this way will it be possible to secure a well balanced development of all sections of the city."

Convenience and connectivity aside, not all residents were fans of creating a central freeway that would cut San Francisco in half, including at least one property owner who owned a lot on the proposed route. A city report from late 1934 concluded that all required lots had been purchased, and "The City Attorney has been requested to prepare a condemnation suit for the acquisition of the remaining lot required for the Castro-Divisadero Divisional Highway."

The lot owner lost the fight, and construction between Castro and Divisadero finally began in 1937, four years after the Golden Gate Bridge began to rise. Divisadero Street was widened, graded and linked, but the tunnel, cable car re-routing and other major infrastructure changes never happened along the other parts of the proposed route. Although information is scant about the plans in this era, it seems that local opposition made extensive road development difficult, in addition to the distractions of the Great Depression and World War II.

But the Divisional Highway dream lived on at least until the mid-1940s. In 1944, the city published this map of possible developments (from Walking SF, via SF Mission):

However, in 1945, with the war over, city planners quickly embraced a grander vision. It was the so-called Master Plan, which would outline a network of freeways, as well as new housing developments and other infrastructure improvements, to be realized throughout the city. Although the Castro-Divisadero connection was already in place, the Divisional Highway overall was sidelined to be nothing more than a local north-south artery in favor of a big route up Van Ness.

SF Department of City Planning

Today, we have a road that feels almost indistinguishable as it goes from Divisadero to Castro Street. Passersby are usually more interested in an elaborate Santa Claus display that pops up on the front of a residential house every winter than questioning why the two roads merge into one.

But this small connection from decades ago marked the start of our current era of city development. Neighborhood associations were popping up around the city, and the power of democracy and community engagement was just beginning to make a huge play on city construction and infrastructure (whether for or against major projects).

In the following decades, as the city began building freeways up the Embarcadero and through SoMa, citizens were able to block the more extensive plans. Today, Van Ness is still a surface street even though it's officially part of the 101, and the Panhandle is still a park. But those stories are for another time.

And there you have it, Hoodline readers. Thanks to a small neighborhood association and some rallying of residents in the 1930s, you can now bike, skate, stroll or drive all the way from The Mill to Hot Cookie without leaving Divisadero or Castro Streets. And that is something to be grateful for – even though we may also be glad these erstwhile neighbors didn't get the full Divisional Highway built.

(Image: torbakhopper)