[Editor's note: Central City Extra, our newspaper partner in the Tenderloin area, has begun a series covering the people that make up the neighborhood. Here's the first installment, by writer Tom Carter with photos by Paul Dunn. You can find The Extra's April issue at locations around the neighborhood, or in PDF form here.]

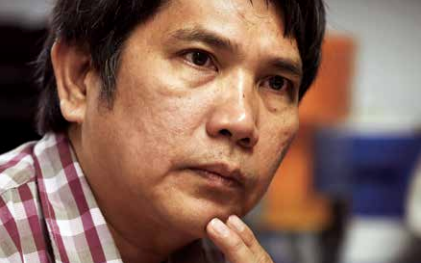

Lorenzo Listana can tell you something about changing fortunes. Thirty-five years ago, he was being tortured in a Manila prison, struggling to stay sane. It was near the end of the 10-year martial law era of Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos. A curfew stopped everyone at night and civil rights were nonexistent. Listana and 18 fellow student activists protesting the conditions were arrested and jailed.

"Yes, tortured, some of us every day for a month,” Listana says. “Physically and mentally. It was hard. We were rounded up without charges."

“They let us go after six months, ya, ya,” Listana says, emitting his characteristic punctuation, as a dismissive laugh that said good riddance to rotten times. Marcos fled to Hawaii in 1986 and Listana, with others, persevered. “I was one of 10,000 people who filed a suit against him there. And we won.”

Lorenzo Listana, a Curran House resident since 2005, is the community outreach coordinator for the TNDC, which owns the building.

Reviled by his victims, beset by illness, Marcos died in exile in Hawaii in 1989, enduring as Listana’s dark memory of what a dictatorship can bring.

Now, at 54, Listana enjoys life in the country of his dreams with his very active family — his wife and four children — in a three-bedroom apartment on the eighth floor of Curran House, while working as a community organizer, a job he loves. “And I have a community here,” he says with satisfaction.

The community is Curran House, a picture of diversity. According to the Tenderloin Neighborhood Development Corporation's 2014 figures on Curran households, Latinos, Asians and African Americans are each 26.5 percent of the resident population that totals 150 to 200. Whites are 4.6 percent, “other” 14 percent and 1.5 percent are “unknown.”

Curran’s polyglot scene keeps evolving.

Listana said that just recently, he met a new family from Honduras in the complex’s communal laundry room. Listana works with his Curran House neighbors and, by extension, the 3,400 residents in TNDC’s 31 buildings of low-income housing, mostly poor folks whose annual incomes typically range from $5,000 to $20,000. At Curran House, rent is based on income, allowing up to $70,000 for large families. The Listanas pay $1,222 a month.

'We Feel Safe'

The modern building has 14 facade balconies and has won 10 architectural and affordable housing awards. Designed by San Francisco firm David Baker Architects, Curran House sits a half-block north of Taylor Street Center, a four-story halfway house for 210 men and women, former state prisoners working toward their eventual release. The neighborhood is rife with drug-dealing, too. But the Listanas are unfazed. “We feel safe,” he says.

He supervises two staffers who work with TNDC residents in group meetings and one-on-ones, encouraging them to stand up for their rights, pursue a better quality of life and to form or join community organizations that seek social improvements. In other words, engage well and evolve positively.

The first TNDC group that Listana played a major role in creating was the East Tenderloin-TNDC Resident Council, sworn in last year at City Hall by District 6 Supervisor Jane Kim (see The Extra, July 2014 PDF). Two more resident councils have been formed since. Listana supervises a third staffer who identifies residents to train for leadership roles.

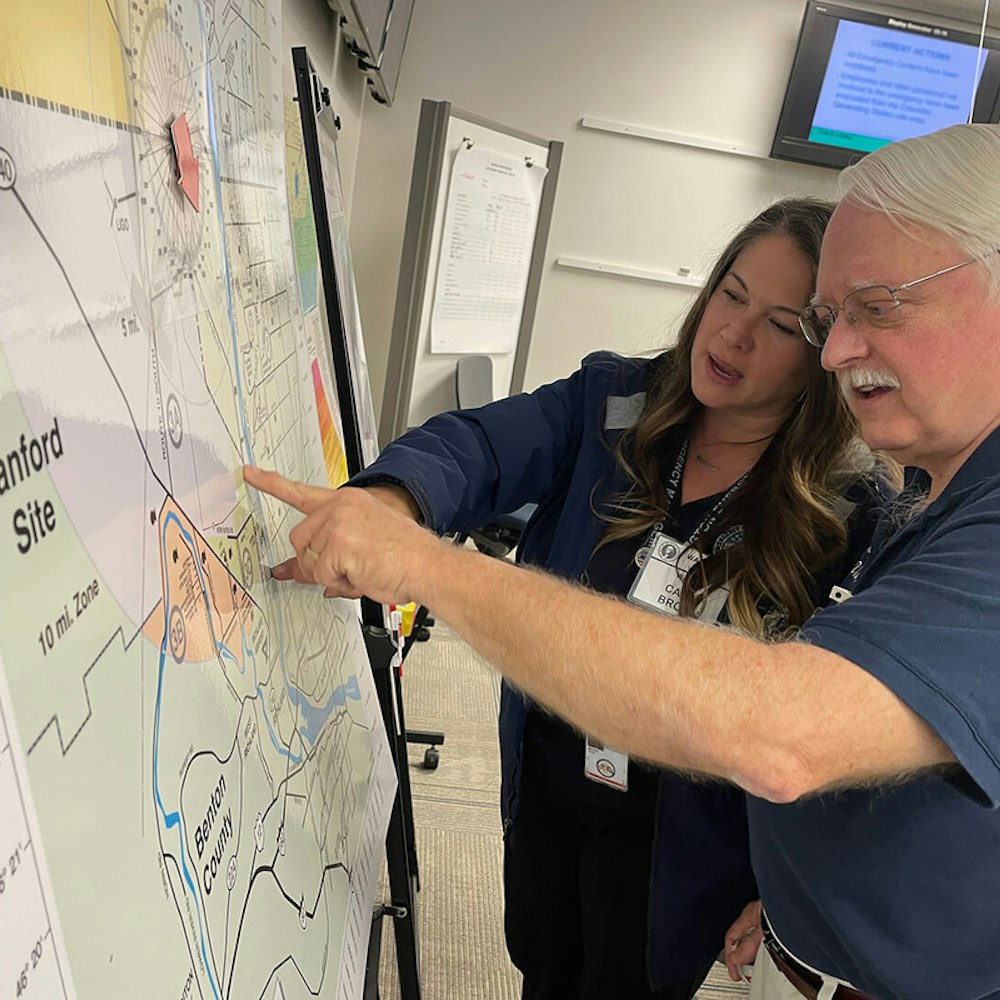

Listana, left, meets with TNDC staff Guled Muse, center, and Siu Cheung.

Devoted to his tasks and always cheerful, Listana seems a natural for the job. “TNDC is a catalyst, a proactive organization,” he says. “They don’t just wait. They act when they see a need.” What gratifies him most about mobilizing people is when they feel empowered. “They get to express their feelings. It makes a difference in their daily lives — if we are organized, then we can improve the community.”

Listana also coordinates the cultivation of the 3,500-square-foot Tenderloin People’s Garden at McAllister and Larkin streets, a city-owned power station plot that TNDC leased and transformed to raise their residents’ healthy-food consciousness. In the middle of a concrete jungle, a cadre of 380 volunteers have tilled its tidy rows since 2010, and the emerald patch has responded, bearing tons of picture-perfect vegetables for volunteers and other TNDC residents.

In his free time, Listana takes on a traditional Filipino activity. As a founding member of the Tenderloin Filipino-American Community Association, he organizes workshops for the residents and TNDC staff to make Parol lanterns to be carried in an annual parade South of Market before Christmas.

Each large, boxy lantern symbolizes a different theme. For example, one wrapped in rope indicates a community bound together. Competing with up to 32 other Filipino organizations at Yerba Buena Park in the Parol Lantern Festival, Listana’s group won the best-lantern contest in 2010 and 2012 and finished third last year.

The American Dream

As a young man, Listana imagined the United States as a land of opportunity where he could get a fine education for his children, education having been in his father’s dreams, too.

Listana grew up in Daraga in Albay Province, a 10-hour bus ride south of Manila. It’s a hot, sticky, farming community of 115,000, average temperature 81 degrees, rain year-round. The community had large populations of Filipino, Chinese, Spanish, some Koreans and Indians, and many intermarried, Listana says.

He knew diversity and pockets of poverty. His father, an imaginative man of action, was an inspiration. “My father was the first of eight children to graduate from high school,” Listana says. “He became an entrepreneur. He opened a shop and sold crafted goods made from abaca fiber. We were the first to export out of Daraga in the late 1960s.

“He sent all of his nine children to school and he helped his siblings, too.”

Listana went away to Manila to college. Democracy, affordable education and human rights weighed heavily on his mind. Eventually, after marrying Cecilia, his wife of 25 years, and starting a family, he envisioned a better life in the U.S. where his children could benefit from good schools, and he planned for it.

Cecilia came to the U.S. first. She got a job in SoMa with Aeroskin California Inc., a wet suit maker, and had an apartment there. In 2005, Listana arrived with their two boys and daughter. He immediately had a stroke of luck that has enhanced his family’s well-being.

“It was like I won the lottery,” he says, still wide-eyed at the memory.

He did, in fact, win the lottery. But it was for low-income families applying to live at Curran House. His was the eighth name drawn for one of the 14 studios, 15 one-bedrooms, 14 two-bedrooms and 24 three-bedroom units. Ten of these are for formerly homeless families, and 10 are subsidized by the federal government as Section 8 housing.

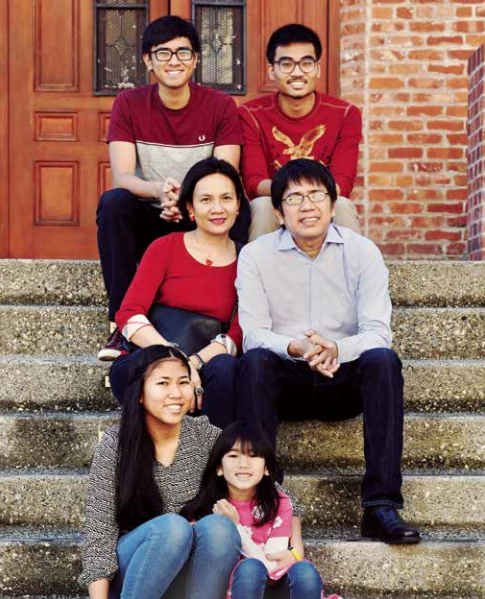

Cecilia and Lorenzo Listana, center, with sons, above, Joseverino Paolo, 23, left, and Nicu, 21, and daughters Precious, 18, and Gabrielle, 7, below.

“I got to choose our unit,” he says. “Otherwise, we couldn’t live in San Francisco, or we’d have to live with relatives.” He has four family members in the city. “I have a nice place compared to people who have been here (San Francisco) a long time and can’t find their way out of poverty.”

At the time, he worked part-time at Aeroskin, as a youth counselor at Burrell Place and as an administrator at another group home for disabled children. Getting hired to help with the 2010 census led to another piece of luck. Steve Woo, then coordinator of TNDC’s Community Organizing Department, became his supervisor. Listana and six other Filipinos traversed the neighborhood, knocking on an estimated 5,000 doors, encouraging residents to fill out the census questionnaire.

“I didn’t know that there were a lot of Filipinos here,” Listana recalls. “I went to different SROs and saw their situations. Some were not fit for human beings. Some didn’t have electricity. I was shocked. It wasn’t my idea of America, that poverty was a part of the city, and rich people just a block away. I knew about poverty. And here it was the same!”

At one place he saw 10 people living in one room. The grandmother had to sleep across four straight chairs. That experience led him to organize the neighborhood Filipino American group. Woo was impressed and hired him as a TNDC community organizer.

“He was in charge of the canvassers and he was a hard worker, a good organizer,” said Woo, now a senior planner at Chinese Community Development Center. ”He’s a good guy, smart, passionate about helping the community. He’s a good father, too. Four children? I don’t know how he balances it all.”

Busy Schedules

The Listana kids are realizing the family’s education goals. Paolo, 22, the oldest, just graduated from San Jose State with a degree in business administration. Niku, 21, is majoring in computer programming at San Francisco State. Precious, 18, the oldest girl, is valedictorian at Sacred Heart Preparatory where she’s a three-year veteran of the debate team and on the Student Council. Gabrielle, 7, attends Presidio Knolls, a Chinese immersion school in SoMa, which Precious also attended.

Schedules are so tight that the family doesn’t have much time for outings together. Both girls are involved with the Tenderloin Boys and Girls Club, and Precious has a host of other commitments. But Sundays find them all walking to SoMa’s St. Patrick’s Catholic Church across from Yerba Buena Park to attend 12:15p.m. Mass.

Precious has been an altar server since 2007 and reads Prayers of the Faithful and parish announcements from the lectern. Afterward they go to lunch, often to Inay, a Filipino restaurant in the Metreon food court.

“But my concern is more profound and deep than just for Filipinos, it’s about social justice,” Listana was saying at the table one Saturday after lunch in their apartment. He is for the entire neighborhood. As he has said before, “We would like this community improved, but with us in it. We want to be included in making the community better.”

Joseverino Paolo Listana, 23, left, and brother Nicu, 21, attend Mass at St. Patrick Church on Mission Street on a recent Sunday.

Cecilia and Paolo were out somewhere. Precious was listening, and Gabby was curled up on the sofa she uses as a bed at night, her nose in her dad’s iPad, a birthday present from Cecilia. When everyone’s home, the family speaks mostly Tagalog. “She (Gabby) likes Brainpop,” Niku offered from the sink, where he was washing the lunch dishes. “Anything basic that has to do with science or math.”

Precious had delivered a speech the week before at the Don Fisher Boys and Girls Club on Fulton Street as she vied to become the citywide club’s Youth of the Year. She was interviewed by five judges.

“The speech was about my challenges as an immigrant and how the (TL) clubhouse helped me see the Tenderloin as my home,” she says, her half-inch-over- 5-foot frame perched on the sofa’s arm. “If I can take advantage of my opportunities, I can step up and be a leader. I have developed into that kind of person, and I am positive that they (the judges) got that message.”

She didn’t win, but as a finalist she picked up a $2,000 scholarship to further her education. Her leadership is a matter of record, and where it will lead is anybody’s guess.

She is on the San Francisco Youth Commission, representing District 6, chosen over other candidates by Supervisor Kim after interviews and written testing. The commission advises the mayor and the supervisors of the needs of young people throughout the city. The day before, she had helped organize and host a Youth Commission meeting at Boeddeker Park with about 60 in attendance.

‘I was intimidated at first’

Precious now awaits a result that could complicate her commission commitment. In October, she was one of 160 students chosen from around the world to read their papers written on food security at a four-day Global Youth Conference in Iowa. Standing in front of the predominantly white crowd, she realized she was the only Filipino.

“I was intimidated at first,” she says, “But I got through it.” She paused. “I decided not to take it as a problem. And I could start conversations on my own. It was an opportunity to represent myself and get to know people.”

That “value,” she says, is something her parents promote. The paper was entitled “Gender Inequality in Somalia Prevents Food Security,” one of 19 topics covering 50 countries that the organization offered to interested students.

“We were all connected by the subject,” Precious says. “I did have help from my teachers.”

While there, she applied for a two month, all-expenses-paid Borlaug Ruan internship. It’s a World Food Prize program that places high school students in 31 of the world’s agricultural research centers from Bangladesh to Brazil to expand their study and inspire careers in science, agriculture and global development. Precious thinks she did well and, if selected, would choose India or Ethiopia to go to study.

District 6 Youth Commissioner Precious Listana, center, helps facilitate a youth forum at Boeddeker Park with Curran House residents’ representative Sharen Hewitt, left, and Treasure Island resident Aquarius Porter.

Getting the internship would mean District 6 wouldn’t be represented on the Youth Commission for two months. And that, she says, could be a problem. But her year on the commission would be up before college starts in the fall. She dreams of attending Harvard, but would gladly settle for UC Berkeley.

Her father’s deep-seated feelings for inclusion seem to have influenced his daughter’s attitude about track at her high school. She was on the track team for three years and the cross country team four years, forgoing her senior year of track because of her growing organization obligations. (Precious is also vice president of the Keystone Club of the TL Boys and Girls Club whose high school members research and report on social topics such as teenage suicide and Internet addiction.)

“Cross country is more team-oriented,” she says. “That’s the way we made it (so) to strive a little harder. There’s no ‘I’ in cross country. It’s more of a family. Every person counted. It’s more my sport.”

There are dozens of activities that bring the mix of Curran House residents together periodically, from tending the rooftop’s 22 fruit- and vegetable-bearing planter boxes to celebrating an array of ethnic holidays.

But it can’t be taken for granted that bias doesn’t show up someplace, sometime.

Precious recalls that when she arrived in the United States at age 9, “it was a cultural shock.” She was used to being surrounded by Filipinos. At the Chinese immersion school she was “bullied” for her accent, which she has since lost.

“I had a lot to learn,” she says, “and it was a blessing in a way. It made me more understanding of different lifestyles. Riding the elevator (here) people always acknowledge each other and say, ‘Have a nice day.’ My friends are shocked at that. But it’s very beautiful. And I love the diversity of this place.”

“It’s the microcosm of the Tenderloin,” her father said.

Afterward From Central City Extra

TL’s diversity emerges in Extra’s new neighborhood series In the heart of San Francisco, amid its 195 U.S. census tracts, the gritty Tenderloin, disparagingly known as the city’s armpit, is nonetheless a paragon of diversity. As data from the four census tracts (122-125) that comprise the neighborhood show, diversity is more than race, though that’s the common perception.

A good guess why the TL is blessed this way is because it’s our poorest neighborhood. If you’re impoverished or low-income, the Tenderloin, with its chorus of nonprofits bolstering the city’s social safety net, is the place to go for a helping hand. The middle class and wealthy, of course, settle comfortably in other enclaves.

Central City Extra went looking for a microcosm of the Tenderloin’s diversity, to visit the residents and ask how they get along in the cauldron, hear their stories, learn of their experiences, see if there’s a lesson there.

Resident tending one of the rooftop garden plots. Photo by Brian Rose/David Baker Architects

We found our prize in census tract 125.01, the third most congested area in San Francisco, home to 5,335 people. The most congested is just across Taylor, and next is tract 122, near the hood’s northwest corner. Our microcosm is Curran House within the tract bounded by Taylor, Turk, Leavenworth and Ellis streets. It’s on Taylor, just up the block from a blue, five-story halfway house for ex-cons. A half-block away is the notorious intersection of Turk and Taylor that the cops call “ground zero for drugs and violence.

The eight-story Curran House is one of Tenderloin Neighborhood Development Corp.’s 31 low-income hotels and apartment buildings in the central city. Built in 2005, it is named after Sister Patrick Curran, a Franciscan nun who was executive director of St. Anthony Foundation in the late 1990s. It has won 10 architectural awards for the design sensibility that it’s brought to the concept of affordable housing.

The Extra begins its series with the story of Lorenzo Listana and his Filipino family. They live in one of 67 apartments housing people from five continents and dozens of countries. Sharen Hewitt, the building’s former tenant foreman, describes them all simply as “beautiful people.” She provided introductions to enable the series undertaken by The Extra’s longtime community reporter, Tom Carter, and award-winning photographer Paul Dunn.