The water still flows down from the shrinking shores of Hetch Hetchy to the sprinkler-fed lawns of San Francisco city parks. But after the fourth year of little rain and almost no snow, California is going into a state of emergency.

Governor Jerry Brown has ordered a mandatory 25 percent statewide reduction in residential water use.

Snowpack in the Sierras, which feeds California's surface water for the remainder of the year, was this April at an all-time low in recorded history, lower even than the faltering snowpack concurrent with the 1977 drought in California.

In fact, there is no longer a pack. According to the state Department of Water Resources, "The California Department found no snow whatsoever today during its manual survey for the media at 6,800 feet in the Sierra Nevada. This was the first time in 75 years of early-April measurements at the Phillips snow course that no snow was found there." The ensuing headlines have been dire.

How does San Francisco measure up? What is its impact on the water shortage?

As part of an effort to follow the drought and its effects, we're taking a closer look at local water use, conservation efforts being made around the city, and what changes you're likely to see over the next couple of years.

"Some Of The Cleanest Drinking Water In The Country"

California has a messy history with water, and puzzling out its water rights, obligations, agencies, uses and responsibilities takes time. The media explosion surrounding the current drought isn't just a result of its prominence in the popular imagination, it's a result of logistical difficulties in seeing the whole picture.

Hetch Hetchy in 1939, via San Francisco Public Library

San Francisco is unusual among California's cities in two respects: it is relatively dense and cold, thus hostile to water-guzzling residential lawns and swimming pools; and its water is fed almost exclusively by a reservoir 180 miles away, in the Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite.

Already, then, San Francisco is an anomaly in the story of California's water use. Add to that the fact that the city is one of the state's most temperate, which further eases the burden of its water use.

By the numbers, San Francisco's residential per capita water consumption ranks among the lowest five in the state: around 45 gallons per person per day. Compare that to districts like Coachella Valley or the Santa Fe Irrigation District (282 and 345 gallons per person per day, respectively) and San Francisco appears to be exemplary.

Indeed, over the past six years, the water level in Hetch Hetchy has undergone regular, predictable oscillations in water level while delivering a stable water supply to the South Bay and San Francisco County.

"The Hetch Hetchy Valley, California," late 19th century, painting by Albert Bierstadt. Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, MA

"What's key to understand," explains Charles Sheehan, the communications manager for San Francisco's Public Utilities Commission, the agency that sells and manages water in the county, "is that we are among the lowest water users in the state. We do a very good job of conserving and of using as little water as possible."

But this is only part of the picture. The fact that San Francisco's water comes safely from Hetch Hetchy, famously "pristine," among the cleanest in the country, and "unfiltered," is deeply typical of California as a whole: we don't see where our water comes from. The valley was on par with Yosemite Valley itself for picturesque natural beauty, and the construction of the dam nearly one hundred years ago became one of the country's formative environmental controversies.

Drought Mitigation

Over the past couple of years San Francisco has made some steps to stabilize and conserve its water, and not simply by asking its residents to curb water use. (In fact, because of the city's population growth in recent years, the drop in per capita water consumption has resulted in a near-zero net difference in citywide water use.)

A view of the Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct, parts of which will be getting repairs. Photo by Margaret Lukens/Preparation Nation.

In an April 1 press release, Mayor Edwin Lee's office acknowledged the governor's statewide call to conserve water. The announcement was largely a commendation of conservation efforts in the city that have already taken place: a mayor-requested 10 percent reduction in water use by city buildings and departments, which was exceeded by an additional 4 percent last year, and a 20 percent reduction in residential per capita water use over ten years.

There are other water-saving efforts being implemented by different agencies in San Francisco that bear mentioning, although not all of them are designed to conserve water.

Last year, Supervisor London Breed put forward unanimously-approved resolutions that called for the state to fund San Francisco for specific drought mitigation measures—"drought mitigation measures" meaning not simply conservation, or use reduction, but securing a continued water supply.

The measures included the toilet buy-back program, a $22 million aqueduct rehabilitation in Yosemite that would repair damaged pipelines and allow San Francisco to access more water from Hetch Hetchy, and an effort to diversify San Francisco's water by mixing groundwater into the drinking water supply.

A sample high-efficiency toilet, photo courtesy American Standard.

Note that of the three, only the toilet buy-back program is aimed at changing end-use consumption.

According to Breed's legislative aide Conor Johnston, Breed "is also now working with Supervisor Wiener on legislation to require large new buildings to incorporate greywater collection and recycling," another measure that would contribute to conservation.

Brown Is The New Green

The city's Rec & Parks Department, the agency who decides when and how much to water the city's parks, did achieve changes in water use last year. According to a directive from the RPD's general manager, dated January 2014, when RPD opted into the SFPUC's requested voluntary 10 percent reduction in water use, strategies for conservation included turning off certain decorative water displays, reducing the duration of irrigation, irrigating at night, and increasing irrigation monitoring, with the stipulated penalty that violation of the voluntary reduction was a fireable offense.

Connie Chan, Rec & Parks' deputy director of public affairs, said that goal had been exceeded. According to Charles Sheehan, most of these and other municipal savings were achieved by "simple conservation": fixing leaks, replacing old fixtures, and cutting back on irrigation.

At the same time, as you might notice, the city continues to water its parks prominently, many of them even in the middle of the day when the amount of water lost to evaporation through sprinkler irrigation (already the least efficient common method of irrigation) is highest.

Sprinkler irrigation in May in Golden Gate Park. Photo by Camden Avery/Hoodline.

This is another interesting water fact: according to another memo from the Director of Operations of Rec & Parks to Phil Ginsburg, the reason the city continues to water Golden Gate Park and Alamo Square and the Marina Green and Civic Center Plaza and Dolores Park in the face of a years-long drought is because these parks were planted with non-drought tolerant grass, because the city's department of the environment banned the invasive, drought tolerant alternative species, which means the Marina Green alone would take an estimated $450K to re-sod if and when the drought ends.

The continued watering of San Francisco's parks might spark some questions particularly in light of the city's "brown is the new green" anti-watering campaign, and in the context of the Governor-issued mandate that bans, among other things, watering with potable water.

According to Chan, water used by Rec & Parks is bought from the Public Utilities Commission and paid for out of the RPD's annual operating budget. For the fiscal year ending in 2015, the total budget was set at $164 million, roughly 50 percent of which was earmarked for operating costs.

We asked Charles Sheehan from the Public Utilities Commission where the water used to water San Francisco's parks comes from. The answer is complicated.

"The parks in San Francisco get their water from different sources," Sheehan said. "Sharp Park and Harding Park here in San Francisco use recycled water. We recently completed a recycled water project last year and a couple of years ago we completed another recycled water project, so that we could water Harding with recycled water. Those are relatively new but completed."

Harding Park Golf Course on a winter afternoon. Photo via Wikimedia.

Golden Gate Park, on the other hand, is watered from the city's groundwater supply.

The PUC is also developing efforts to diversify the city's water supply and in fact is in the middle of a major transition to incorporate 4 million gallons a day of groundwater into the drinking water supply.

"This is all supply diversification," Sheehan said.

One project currently in environmental review is the Westside Recycled Water Project, he said, which will take recycled water to Golden Gate Park, Lincoln Park, and parts of the Presidio. That project will start construction in a year, at which point the groundwater used to supply those parks will be used to supplement the drinking water supply.

This will also involve a new recycling facility on the site of the Oceanside Wastewater Treatment Plant, which currently handles about a fifth of the city's waste and stormwater runoff.

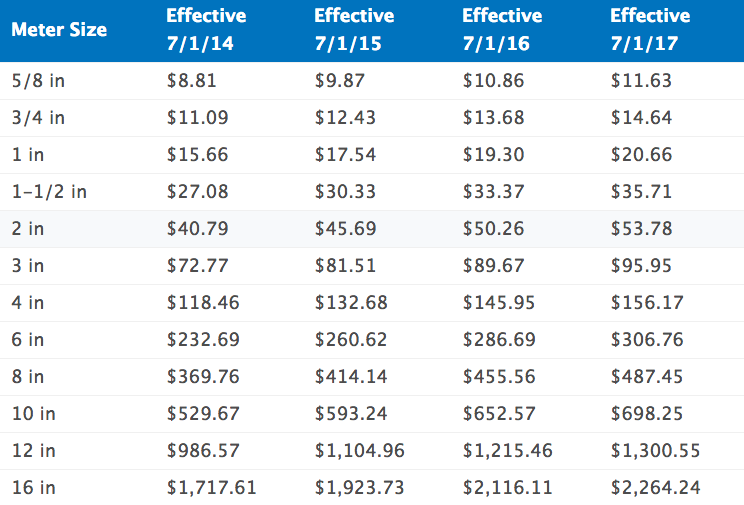

Despite a recent announcement that it would begin raising wholesale rates that neighboring municipalities would likely be forced to pass on to its retail customers, Sheehan said the SFPUC would not be changing the details of the tiered retail pricing for San Francisco customers, which is already scheduled through 2017.

Excerpt of the rate schedule for single-family homes from the SFPUC.

Sheehan said that like other counties, San Francisco had found a tiered pricing schedule helpful in encouraging more conservative end-use consumption, but that it was expected to remain stable.

"We have a reserved contingency fund for just these tough years," he said, "and we're doing some belt tightening and we're also dipping into our reserves so that we don't have to change our price package."

San Francisco retail water users, in other words, are likely not to be made to feel the cost of water scarcity, which might raise questions about the extent to which further conservation is actually going to happen.

Watermelons In The Desert

Part of the difficulty in assessing San Francisco's water use is exactly the same isolation that allows it to look so good on paper: residents may use only 45 gallons per person per day for drinking, bathing, cooking and gardening but none of the meat or produce consumed in San Francisco is grown there.

The reason San Francisco has such a low average water use is, in part, because it is allowed to distribute the water burden its food requires into other parts of the state, like the Central Valley.

It's this agricultural burden, in part, that in light of the current drought raises questions about the efficacy of what is, essentially, growing strawberries and watermelons in the desert, three seasons a year.

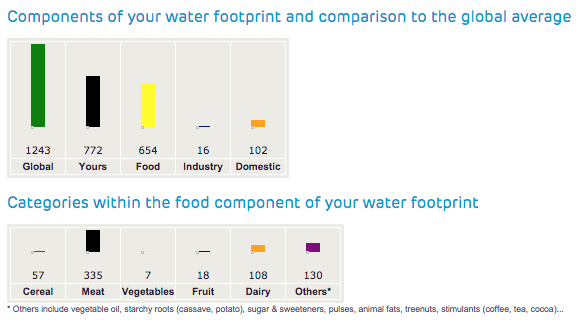

If you're curious what the real impact of your gastronomical behavior is, there are use calculators that paint a fuller, more complete picture of how many thousands of gallons of water a year you're using in Bakersfield. The primary factor that tips the scales for most consumers is being carnivorous.

Sample use calculation for a meat-eating Californian, via the Water Footprint Network.

Of course the fact that agriculture in California is, in essence, providing food for the rest of the country in a naturally arid landscape also contributes to the state's water shortage.

Actually much of this shortage has yet to be realized, because Central Valley agriculture is watered using the valley's underground aquifer system. The aquifers, which fill and re-charge over centuries and millenia, are currently in "overdraft," a situation that occurs when more water is being removed than is being recharged by rainfall.

So much water was pumped out of the ground in Salinas during the 20th century that the ground level fell in some places as much as 30 feet; once that happens, the aquifer below takes longer to recharge, because the sediment is compressed.

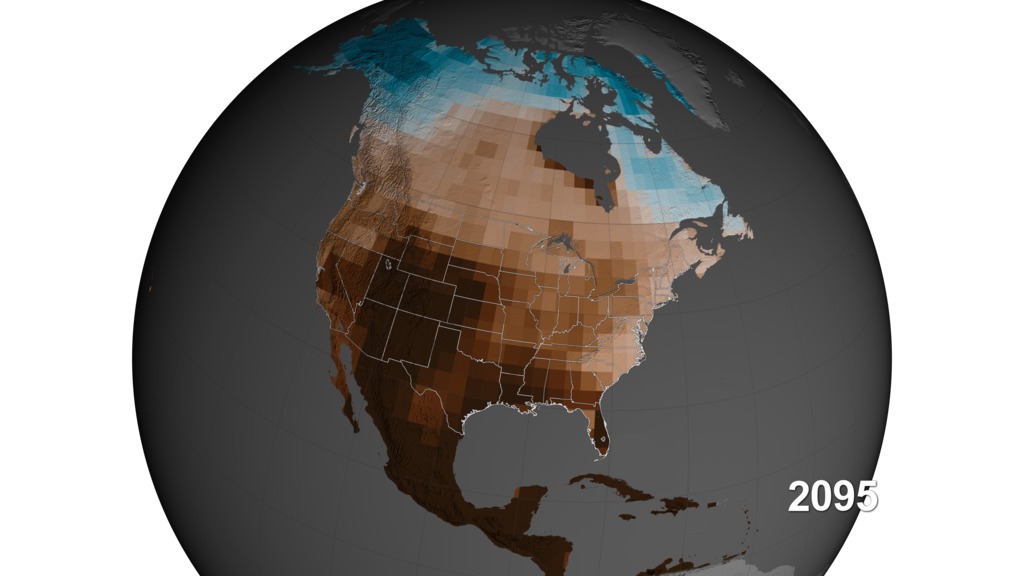

Earlier this year, NASA predicted that the United States would soon begin to see droughts lasting not two or three years, like California's worst and most recent similar drought, not 10 or 12 years, like the Dustbowl, but more than three decades.

A dire visualization of the new long-term drought conditions predicted by NASA.

The last time California endured a prolonged drought this severe was in the late 1970s. Cars went unwashed, people skipped showers, toilets went unflushed. People made do. The drought and its effects were continuous with and, ironically, subsumed by the following energy crisis.

Writing from that last drought, in an essay called "Holy Water," Joan Didion said: "A certain external reality remains, and resists interpretation. The West begins where the average annual rainfall drops below twenty inches. Water is important to people who do not have it."

What remains unclear, apart from the details of the future of water scarcity in California, is what role, if any, San Francisco will decide to play in redefining the state's water politics.