On the corner of Eighth and Folsom, after bending down to press a call box and speaking to a crackly voice on the other side, and after riding up a freight elevator with a mirrored ceiling hovering disconcertingly above, and passing several nondescript offices, as well as a dance studio, you will find what may be the most unique library in San Francisco.

“When we started this, I didn’t know how many other people would be interested,” said Megan Prelinger, who, along with her husband, Rick, founded the Prelinger Library 11 years ago. “My initial assessment of the number of people who might be interested was like five to ten to 25 people a year. By year three we were at 700 visitors a year, and by year four we were at a thousand visitors. It was a bit of a shock to the system.”

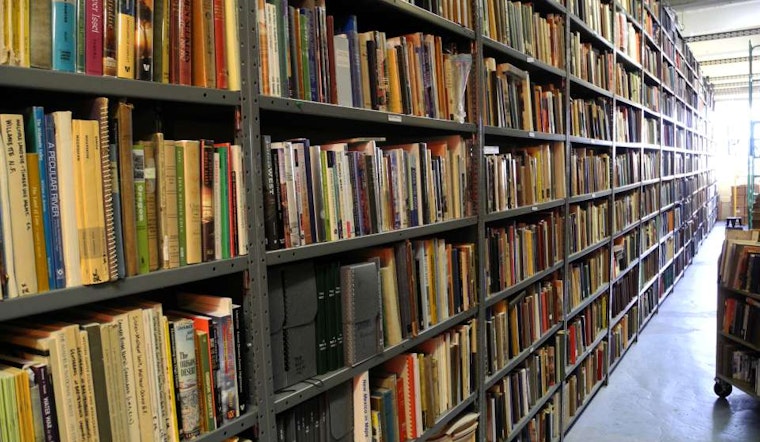

By the standards of most other libraries, the Prelinger Library is small. Consisting of just three aisles of books, plus a stack of boxes for odds and ends in the back, what the library lacks in comprehensiveness it makes up for in content.

On its website, the library is billed as a collection of “historical ephemera, periodicals, maps, and books,” which is to say that it is an attempt to collect and catalogue items not meant for posterity, that were created only for a particular month or week. A quick browse through the shelves reveals the artifacts of this quest: vintage TV Guides, old trade periodicals with names like "Retail Lumberman" and "Missiles and Rockets", forgotten books like Milton Wend’s How to Live in the Country Without Farming, various maps and monographs, and government studies of different stripes. All of this, the Prelingers claim, was inspired by their curiosity around what kind of historical picture one could get from simply looking at the archival evidence that nobody else noticed.

Rick Prelinger

Rick Prelinger

“We’re both document-driven people,” said Rick Prelinger. “We do a lot of work based on what we find and uncover, so a lot of the books and the films and public projects that we’ve done have their genesis in material and evidence that grabs our attention.”

“It’s been 25 years since I first started thinking about what would you get if you looked at evidence in this way and what kinds of patterns are there to be found,” added Megan. “And really there are so many that there’s a lifetime of projects, not just for me, but for the rest of the world.”

Punk rock

Rick and Megan met in 1998. At the time, Megan was a self-described “zinester with a day job and big ideas.” Rick, meanwhile, was living in New York and was working as a moving-image archivist and filmmaker. When he came across an article Megan had written one day, he was enamored enough to send her a fan letter, which blossomed into a correspondence, which in turn grew into a courtship that eventually resulted in Rick moving out west. Soon, they began taking road trips together, leaving their home for days at a time to explore the landscapes around them and to visit small towns. It was during these excursions, Megan explained, that they would stumble across “book barns and reading corners of rural gas stations” and wonder about the value that this literature contained.

Equally as important were their youthful encounters with what they described as San Francisco's and New York’s “punk rock culture” — the independent businesses and meeting spots that were as much about exchanging ideas as they were about anything else. “I had a lot of experience in places like book stores, record stores, and punk rock hangout zones, like Epicenter Zone, that used to be on Valencia Street,” said Megan. “You could just go and spend time around a common interest, and there would be piles of stuff lying around. You could look at the stuff, talk to other people who shared your interests, and you could have any of a million kinds of transactions, from intellectual to musical to poetic, that were not based on a commercial transaction.”

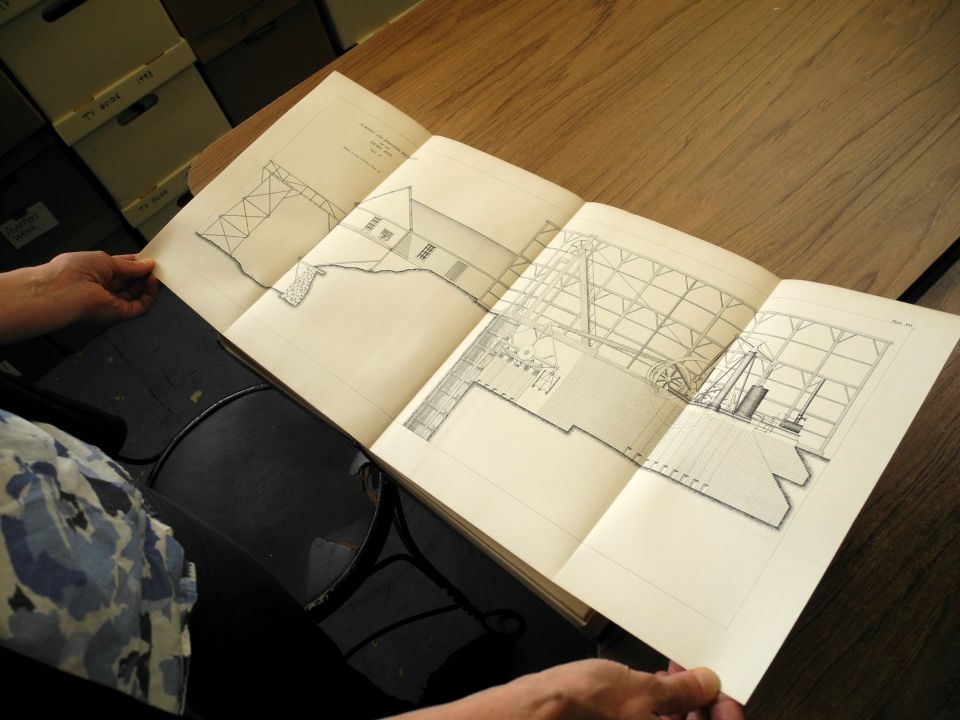

At the same time, both Rick and Megan were collectors who had independently amassed substantial amounts of material. To supplement the Prelinger Archives, a collection of “ephemeral” films that he had helmed since 1982, Rick had been gathering books and periodicals and other printed texts that would help contextualize his thousands of amateur movies and reels. Megan, who had studied anthropology, had herself put together a collection of ephemera in order to “apply anthropology to modern 20th-century American cultural history and try to map out patterns of relationships between people through looking at overlooked evidence.” The result was nine storage rooms full of books.

Megan Prelinger with Annegret Spranger, a volunteer

Megan Prelinger with Annegret Spranger, a volunteer

Fueled by the idea of creating a community center, a place where people could meet to work on projects and inspire one another, as well as answering the question they had posed to themselves while on their road trips — what could all this overlooked evidence teach us about both our history and ourselves? — they decided to start their library. By 2004, thanks to the dot-com bust, they had found a cheap spot. And, after 60 friends came into town to help with an informal “barn raising,” the Prelinger Library was born.

A taxonomy of serendipity

The front door of the library is on the left side of the room. This means that when you walk inside, you will immediately be facing the first of the three aisles, with its tall shelves and carefully arranged rows. Snake your way through the first, around through the middle, and finish off in the third, and you will not only discover the uniqueness of the collection, but the originality of its arrangement. The library is not alphabetized, nor does it adhere to the Dewey decimal or any other traditional scheme. Instead, it uses a “geospatial taxonomy.”

“The leading idea was that this collection should be organized according to an internal logic that was internally consistent,” explained Megan Prelinger, who thought up the design. “We’re not trying to make a picture of the world, but there are through lines that connect the different things that we’re interested in, and so I felt that a taxonomy should express those through lines. It seemed best to start where the feet meet the ground.”

Appropriately, then, the archive begins in San Francisco, before moving onto books about California and the other western states, then through the plains toward the East Coast, particularly New York. Then it broadens, expanding outward to materials more generally about the physical environment, such as geography and geology, then onto natural history, land use, and rural life.

The progression continues on to texts about transportation, crafts, and culture, before shifting to urban planning, which segues to architecture and art. Media follows and includes subjects such as radio, telephone, and film. Next, you’ll find books about science and gender, then family, state, and politics. Before you know it, the shift has been made, finally, to outer space.

“It made sense to extend this idea of a library as a space for exploration, as a landscape to be explored, and to reformulate the whole practice of browsing as a physical process,” Megan said. “That harmonized with our interest in offering a counterpoint to query-based modes of access.”

Even more, this arrangement aligned with their desire to create a space that facilitated serendipitous encounters. “These shelves are a really great forum for discovery of things people didn’t know existed,” Megan went on. “We have scholars who come in here, and they’ll browse for a day, a week, and then they’ll make a pull list and go back to their closed-stack institution and request things that they never could have discovered, because query-based access doesn’t facilitate random discovery, or semi-random discovery, which is what we specialize in here.”

Unexpected art

This approach, fittingly, has led to some surprising results. Although the library has become a predictable haven for likeminded scholars of ephemera, as well as librarians and library tourists, by far its most frequent and active guests have been artists. “We discovered in the first few years that it wasn’t just a repository, it was a workshop,” said Rick. “People come here to make things. And on top of that, it’s also become a place where projects are conceived, discussed, traded, where people come to talk.”

Vanessa Renwick's "Patriot Act" hangs above the front door.

Vanessa Renwick's "Patriot Act" hangs above the front door.

Although they did not initially anticipate this reaction, Rick and Megan have embraced the artistic community and incorporated them into the library’s design. For instance, they now have an artist-in-residence program, where someone can come in for an entire week, rather than the one day per week the library is typically open, to work on a project. Their current artist, Nicole Lavelle, is hosting a monthly performance series called “Place Talks,” which invites half a dozen other artists to present landscape-based interpretive new works. They have also begun offering expanded hours on additional days through the efforts of guest hosts, such as Charlie Macquerie of the Greenhorns, and Carolee Gilligan Wheeler of the Elsewhere Philatelic Society.

Unexpected and unanticipated, all of this nevertheless aligns with what Rick and Megan envisioned for their library — the sense, as Rick likened it, that it is a type of “salon.”

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter to them why you come in, as long as you do. “There are some people for whom a visit to a library is absolutely essential, and there are some people for whom a visit to a library is something that happens when they need it,” Rick said. “We’re agnostic. We don’t care why anybody comes. We just love people.”

The Prelinger Library at 301 8th St. is open from 1pm to 8pm every Wednesday, as well as 11am to 4pm on the second and fourth Saturday of the month. “Place Talks” will next take place on Thursday, October 22nd, from 5pm to 9pm.