[This article from Central City Extra's April 2012 issue is part of a series of excerpts, edited by Marjorie Beggs, from the Neighborhood Oral History Project interviews. Conducted in 1977-78 under a federal CETA contract by Study Center, the publisher of Central City Extra, the interviews help show what life was like across city neighborhoods in this formative era .

The nonprofit has a large original collection of additional oral histories and photos in print form. They (and Hoodline) are looking for people to help digitize and publish stories from the collection. If interested, please contact editor (at) hoodline (dot) com.]

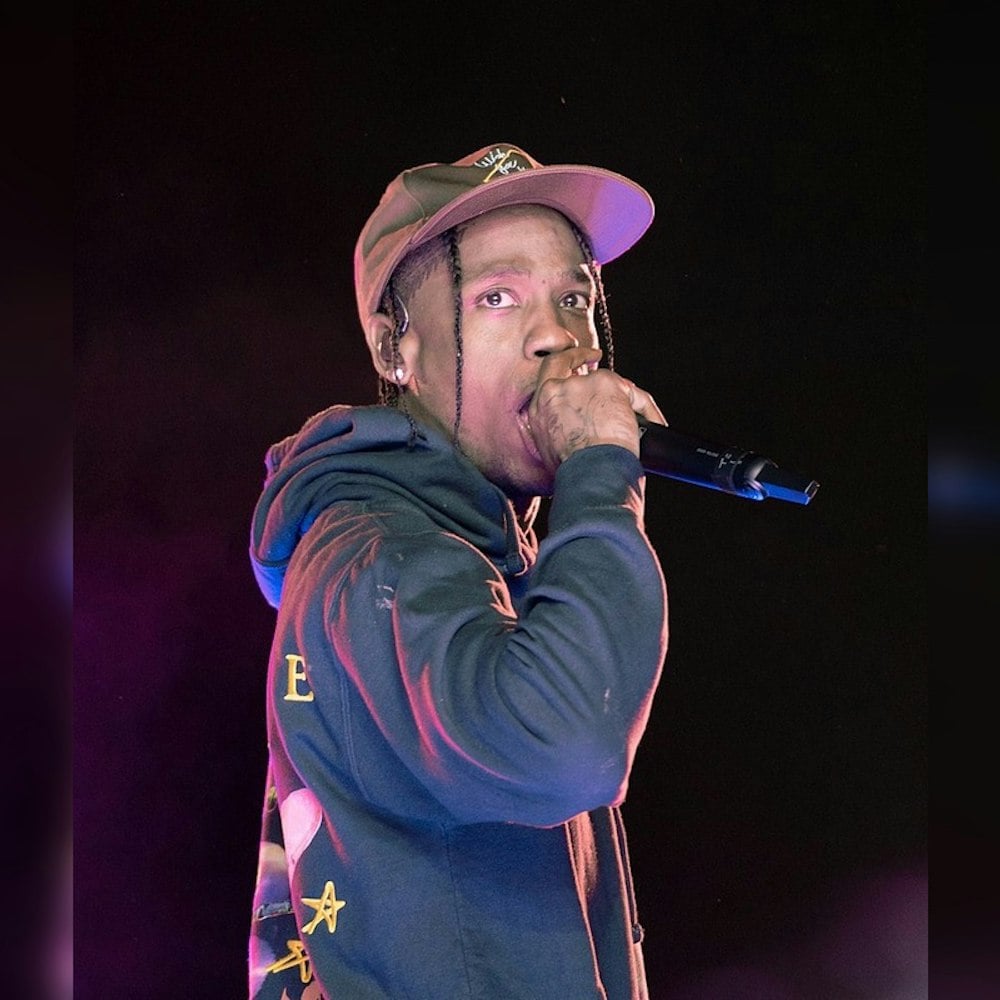

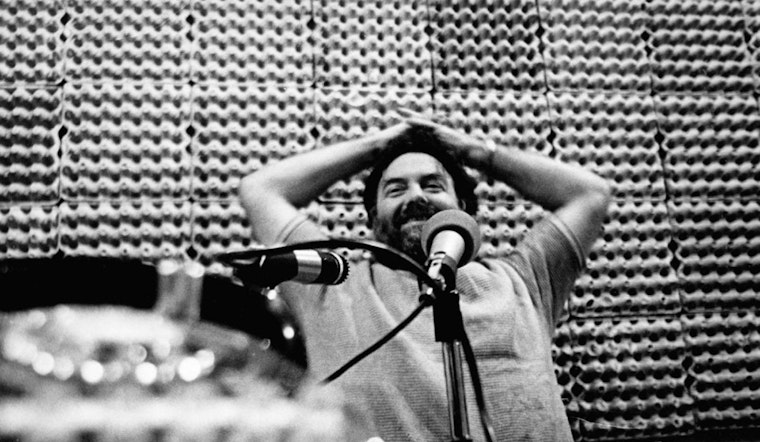

Leland (Lee) Meyerzove, longtime SoMa resident, journalist and activist, was a radio programmer and host of the weekly radio broadcast of Board of Supervisors meetings on KPOO. In the mid-1960s. He was friends with the last of the Beat poets and at S.F. State edited “Transfer,” the campus literary magazine. In the later 1960s, Meyerzove headed up the San Francisco Economic Opportunity Council’s Anti-Poverty Program.

A regular at Canon Kip, a SoMa community resource, he was honored in 1998 by nonprofit housing developer TODCO, which named its new 24-unit building for people with disabilities and their families at 980 Howard St. the Leland Apartments.

Meyerzove was on the board of directors of the Legal Aid Association of California in 2004 and 2005. He died in October 2006.

Following are excerpts from an interview with Meyerzove conducted by Oral History staffers Isabel Maldonado and Lenny Limjoco that was broadcast live on KPOO in 1978.

Study Center: You’re a native San Franciscan?

I was born in San Francisco in 1934 — the year of the big longshoremen’s strike. My mother was having labor pains while the laborers were having their march. At the time, my parents were living where San Jose Avenue and Mission Street meet. I’m a first-generation American.

My mother came to San Francisco because her father was here — he’d come from Eastern Europe before World War I on a “black” passport, which meant that he had no homeland because he wouldn’t go back to Poland to fight the Bolsheviks after the war was over. He’d had enough of war. When my grandfather was 13, someone had marched into his school in St. Petersburg and he was drafted into the Tsar’s army. He’d gotten into that school, though he was a Jew, because he had a relative without children who rose to some minor rank.

My father came to San Francisco as a visitor. He had been in the army in Palestine in 1916 and got malaria there. Later, when he was living in Los Angeles, a doctor told him the weather there was bad for him, so he came to San Francisco but also to visit a friend from Europe who was in silent films here. People thought San Francisco was going to be in competition with Hollywood.

My mother and father met when he went to a theater to meet a date with another woman, but met my mother instead. My mother settled South of Market and here’s an interesting story: When I became chairman of the city’s anti-poverty program, I went to look at some office space on Howard between Sixth and Seventh streets. When I walked in, the lady looked at me and asked if my last name was Drawere [sic]. I said no, but that was my grandfather’s name. With my beard, she said, I looked just like him when he first came over from Europe with my uncle. She’d met them 40 years before when they were rooming at her mother’s and father’s place, which they’d left to her and that she was now managing.

SC: Where did you grow up?

I grew up on McAllister and Divisadero. My first impressions — I was 6 or 7 — were playing at Fremont grammar school and watching my father go off to the Kaiser shipyards during World War II. We lived there until 1944, then moved to Hayes Valley, at Laguna and Fell. What happened was the landlords on McAllister wanted to take our five-room apartment and turn it into two apartments and have us share the kitchen — there were a lot of people coming into San Francisco because of the war industry. There actually was a court battle about the eviction: The owners, to get us out, accused me of urinating out the window. I’m serious — I had to go to court and testify that I knew my way to the bathroom. We won the case, but we moved anyway. A year later, I remember the day all the bells and sirens went off. It wasn’t noon, so we knew the war was over.

SC: What was the city like in the 1940s?

Out in the Sunset there was mostly sand dunes, and Richmond was just starting to get built up. There was a graveyard and church [near Masonic and Turk streets] where we used to play at night, and that helped us get over our feelings about ghosts. The city was small then. Hunters Point was a place you went for picnics and to go fishing. Sutro Forest was the first place I slept outside overnight. You could walk everywhere, from one place to another.

SC: Were there ethnic divisions in the neighborhoods?

At my [elementary] school I had black, Chicano, Native American, Irish and Italian friends. My father spoke nine languages — he was especially fluent in Italian — and he worked for Italian grocers. I grew up thinking I was almost Italian, but I came from a strictly kosher house. Still, my mother used to go around and visit Chinese restaurants and Spanish restaurants in North Beach and learn how to cook different styles. The whole city was very ethnic and multicultural — and many people didn’t consider themselves “white.” They were Italians or Sicilians or Greeks.

When it was time for me to go to junior high, in 1948, we lived in Hayes Valley and it was essentially a Jewish and black neighborhood. There were de facto segregation lines set up — certain people knew that the neighborhoods were going to change — but I quickly found that education in San Francisco was based on class lines. When I went to Presidio Junior High in the lower eighth grade I was doing algebra. When I was moved over to Everett Junior High I was only learning how to add fractions. They felt that those of us living in workingclass neighborhoods didn’t need anything else because we weren’t going anyplace anyway.

SC: Did you keep your friends when you moved?

Yes, I was going to Hebrew School, which is now the Center for the Blind on Buchanan and Grove, and a lot of us used to play basketball at what had been Notre Dame Church. The city bought the church, took out all the pews and turned it into a basketball court. My closest friend Henry Espinoza was taking Confirmation classes at Sacred Heart nearby so we played in the old neighborhood, which we knew really well, even though we lived blocks and blocks away.

San Francisco was a very, very small city. We were used to taking streetcars and we felt quite independent and didn’t feel far apart unless someone moved to the outskirts of the city. For me, the most disastrous was when my friend Eddie moved from McAllister and Divis out to the Excelsior. I remember that going out to see him was just as bad as going out to the country.

Later on, going to high school, it was harder to maintain contact with friends. When I was going to Lowell High School, we had to walk through miles of sand dunes to get out to the soccer field at San Francisco State. People just don’t understand that not long ago, you could walk all over many neighborhoods, but when the city began expanding into the real western areas, the Richmond and Sunset, we became lost.