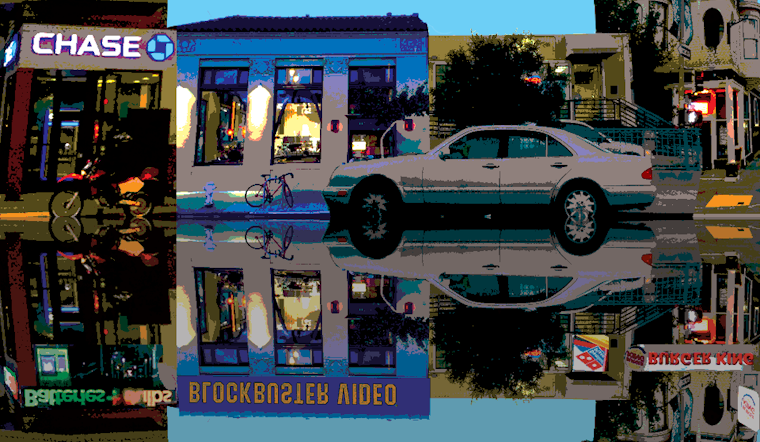

Divisadero is known for its small, locally-owned restaurants and shops. If you didn’t know better, you would think that there was a ban on formula retail in the neighborhood—chains, such as Popeyes and Chase, are rare occurrences along the corridor.

But as neighborhood activists from the '90s will tell you, things could have gone differently. Madrone Art Bar could have been a Burger King, Nopa could have been a Blockbuster Video, BASA could have been a Domino’s, and Chase could have been a Batteries Plus.

In response to the rezoning of Divisadero and Fillmore, which allows for higher-density developments, and the announcement of two large Divisadero condo plans ranging from 60 to 158 units, there's been a lot of talk over what shape housing development should take along Divisadero. As people debate what’s best for the future of the neighborhood, it’s interesting to look back at past decisions that have contributed to Divisadero’s character.

Madrone Art Bar is a designated landmark that was slated to become a Burger King.

Madrone Art Bar is a designated landmark that was slated to become a Burger King.

Richard Kay and Marc Lorenzen, leaders of the Haight-Divisadero Neighbors and Merchants (HDNM), say that they and their neighbors once had to fight to keep chain stores from lining Divisadero. The economic recession of the early '90s had shuttered many shops along the street, but at the turn of the millennium, things were starting to change. Kay described the neighborhood as at a tipping point. “The area was ripe for development,” he said.

Kay and Lorenzen lived in between Alamo Square and Duboce Park in a four-block area with no neighborhood association. “So we had to create some sort of neighborhood group to challenge builders who were just building at will,” said Kay. And so the HDNM was born.

One of the chains the newly minted HDNM took on was Burger King, which intended to move into the space which Madrone now occupies. The building is a designated landmark—once the Theodore Green Apothecary, it was designed by Samuel Newsom, the so-called king of the Bay Area Victorians. But after serving a stint as a falafel shop, the first floor of the Victorian was boarded up and no longer up to code. That's when Burger King decided to move in.

Many neighbors believed that chain restaurants like Burger King would increase traffic, create hazards for pedestrian safety, generate trash and smells, and push mom-and-pop businesses out of the area. So Kay and Lorenzen posted flyers calling for a meeting in the back room of the Ebenezer Baptist Church.

Lorenzen called the turnout “a big cross-section” of the people living in the neighborhood at that time. “Old hippies, homeowners from the black community, older neighbors (like Richard), and me, the new guy. It was interesting because it was a real Haight meeting, you know,” he said, laughing. “People were just yelling out and carrying on.”

But the diverse crowd found common cause in preventing Burger King from moving in. (They also organized to prevent Touchless Car Wash from removing two Victorians to expand.)

“It was great to see the power of an idea with a group of people who coalesced on a challenge,” said Kay. He was quick to give credit to everyone who assembled in Ebenezer Baptist Church that day. “It wasn't just us, but the neighbors who showed up at the meetings and put time in and pursued the projects and goals to make the neighborhood.”

Those neighbors attended numerous hearings in City Hall and organized dozens of people from the community to speak out against Burger King occupying the historic pharmacy. At the hearings, they brought up issues such as the parking and traffic—an argument that got a boost when Burger King, embroiled in its french-fry war against McDonald’s, decided to have a free french-fry giveaway, creating traffic jams across the country right before the hearing.

In the end, parking was the issue that sunk the Burger King. “It was one of the first times that a chain store had been defeated in the city,” said Kay. Soon after, the property became Madrone Art Bar.

The work that went into keeping Burger King out would be repeated each time a chain store the neighborhood opposed tried to open a location along Divisadero. Blockbuster Video considered the location Nopa now occupies, and Domino’s Pizza applied for a permit to open a location at Divisadero and Grove in 2004.

Dean Preston, a neighborhood activist who helped petition against Domino’s and now spearheads Affordable Divis, described it as “wildly unpopular.” Many of the concerns about Domino's were the same as those that had previously felled Burger King: It was an international chain that would drive local businesses out and cause traffic and pedestrian issues. (It didn't help that Domino’s was also viewed as right-wing and anti-choice.)

Preston vividly remembers a packed neighborhood meeting at Club Waziema that the Domino’s franchisee, Wally Wilcox, attended. A woman raised her hand to contribute to the debate, and began by rhapsodizing over the pizza that was already—and still is—in the neighborhood.

“She’s like, ‘Look. We’ve got Tony over at Stelladoro Pizza. He’s got these wonderful, crisp crusts. And we’ve got Panhandle Pizza, with its cornmeal crusts and this great sauce. And [Sam Heng] at Bus Stop Pizza, who has been there forever. What are you going to add to the neighborhood?’

Preston, who described the interaction in an article that September, still recounts the franchisee's response in disbelief. "He stood up and said, 'Shitty pizza that gets there fast.'”

“[The franchisee's] position was, ‘Small businesses aren’t going to move to Divisadero. You guys should be welcoming chain stores if they want to move into this unattractive urban street,’” said Preston. But Preston and many others felt that if chains were kept out, locally-owned businesses would have a shot—a theory that has been proven over time.

Within a month of Domino’s permit application, opponents of the project had gathered over 1,500 signatures calling for its denial. But despite the widespread support, Preston said, “It was a really long shot to win.”

At that point, any project that met code was usually approved; the Planning Commission reserved the power to deny an application, but only if there were “exceptional and extraordinary circumstances associated with the proposed project”—a long shot, indeed. However, after hundreds of residents and the nearby neighborhood groups expressed their disapproval, the franchisee withdrew his application.

“It was after that that we really made the case and said, ‘Look, we shouldn’t have to do this to weigh in on a chain store. We as a community should be entitled to a hearing when a major corporate chain is moving into our neighborhood,’” said Preston.

In 2005, the following year, legislation was passed to require a conditional use hearing for any chain store that wanted to open along Divisadero. That meant that people and groups that felt strongly about a chain would always have a chance to make their case before the Planning Commission—not just in exceptional circumstances.

In 2007, Proposition G was approved by voters, making conditional use hearings required throughout the city. Some districts go even further, banning chain stores completely. In the rest of the city, chain stores can open locations if they fill a need and maintain the character of the neighborhood. Over 70 percent of formula retail applications do eventually get approved, but Preston suggests that the law has deterred the types of chain stores that are not likely to make it past neighborhood opposition, such as shitty pizza.

Batteries Plus tried to move into the building where Chase stands today.

In 2007, Proposition G was tested when Wisconsin-based Batteries Plus tried to move into the location on Divisadero between Oak and Fell that's currently home to Chase stands today. Many residents took a stand against it in the hearing, so Batteries Plus decided to opt for a different location on Bush Street off of Van Ness, where it was able to win approval.

“For the Domino’s case, we were fighting to even be heard at all. Once we changed the law, then in the Batteries Plus case, we had a right to be heard,” said Preston. He called it an amazing example of the power of community organizing. Later, when Chase took over the location, it was not subject to conditional use because financial services were considered exempt—a loophole that's since been closed.

Looking back, Lorenzen and Kay agreed that living on Divis is not a question of whether things will change, but how. “It took a communal effort, but I think a lot of the work we put in early on made the neighborhood what it is,” said Kay. “We surprised ourselves at the success we had against corporations that wanted to build chain stores here. But it’s an ongoing effort.”