This article, written by Jonathan Newman, was originally published in Central City Extra's April 2016 issue (pdf). You can find the newspaper distributed around area cafes, nonprofits, City Hall offices, SROs and other residences, as well as in the periodicals section on the fifth floor of the Main Library.

Despite city efforts to regulate the short-term rentals of San Francisco’s estimated 8,000 residential units that are posted on Internet-hosting venues—spaces once viewed as a cornerstone of long-term housing—thousands of property holders continue to ignore the new rules.

Only 1,680 applicants have sought city approval to rent their residential spaces short-term, according to the Office of Short-Term Rentals. Of those, 1,118 have been approved and 365 rejected, with 197 pending.

Just two of the 210 Airbnb rentals listed in Tenderloin ZiP codes are registered with the city.

In October 2014, scrambling to address the raging housing crisis, the Board of Supervisors, led by then-President David Chiu, acknowledged the erosion of housing stock unleashed by property holders using Internet-hosting platforms like Airbnb, HomeAway and its subsidiary, VRBO, to book their available spaces as short-term rentals — a process dubbed “hotelization.”

Rather than punish the thousands of scofflaws who were profiting by violating the decades-old Residential Rent Stabilization and Arbitration ordinance, which prohibited short-term rentals without strict review and licensing, the board chose instead to regulate the conversion practice, widening the pipeline of revenue flowing to the city's General Fund. Better to offer property holders—both landlords and tenants —a chance to come in out of the cold, the board reasoned.

Chiu’s legislation allowed a permanent city resident to offer some or all of a primary residence as a short-term rental under certain conditions: the permanent resident occupies the primary residence for at least 275 days in the calendar year in which the space is rented short-term, collects and remits to the city the required transient occupancy tax of 14 percent of the rent charged, and obtains a registration number from City Planning, which must be listed on any Internet platform used to book temporary guests. No one had to account for past transgressions, just come on board.

The city’s proffered carrot of compliance isn’t drawing large numbers. On March 22nd, the OSTR held an all-day registration drive at City Hall, and fewer than 10 people showed up. “The event was lightly attended," Kevin Guy, the agency’s director, diplomatically noted. Still, the outreach efforts will continue. Another open house application drive is scheduled during the Earthquake Retrofit Fair on April 18th.

The Office of Short-Term Rentals might be forgiven its growing pains. It has only been operating for eight months, and is just starting to wade into the three-year rolling surf of city Airbnb policy and politics.

Supervisor Mark Farrell and Mayor Lee introduced the idea for the new office last April, a month after Farrell hosted hearings about how to enforce the just-passed rental regulations. He got an earful from housing and tenant activists, home sharers, private developers and city staff, then put together amendments to the new rental laws. One was to create “a single location” where the public could get help meeting the regulations and staff could identify and pursue hosting violators.

It opened on July 30th, three months after it was approved, with a staff of six—three each from the Planning Department and the City Administrator’s Office. Its budget for this fiscal year—$306,351—is less money than the city's allotment for sign code enforcement.

Last year, master’s students in the Department of City and Regional Planning at UC Berkeley reviewed the major Internet-hosting platforms, and estimated that 8,000 short-term rentals in San Francisco were listed on Airbnb and other venues. The students also found, in plain view, 550 property holders offering multiple rental sites—an apparent flouting of the law’s primary residence provision.

Airbnb, known for a cultivated deafness of tone in replying to public concerns, now seems ready to acknowledge there are hosts listing multiple properties on its platform. In early April, Airbnb issued partial data from a self-review that identified more than 670 suspicious listings controlled by nearly 290 hosts. Airbnb told the Chronicle it intends to axe these apparent law violators from its site.

Airbnb won’t release any information on the suspicious hosts, nor does it currently plan to block site access to hosts who don’t display a city-issued registration number. The hosting giant claims it has privately removed more than 215 listings from its San Francisco site in the past 15 months.

A recent informal review of Airbnb listings by The Extra revealed that in the two main Tenderloin ZiP codes, there was a range of offerings, from studios, condos and full homes to standard hotel rooms. (Airbnb's neighborhood site offers the disclaimer that “the Tenderloin is not the most savory cut of meat.”)

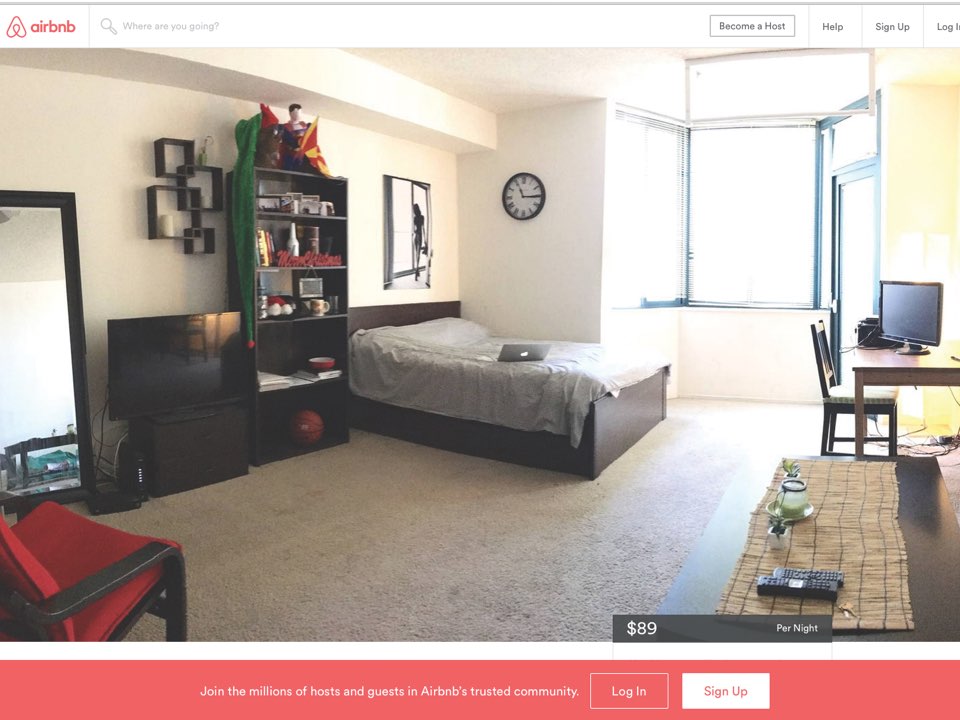

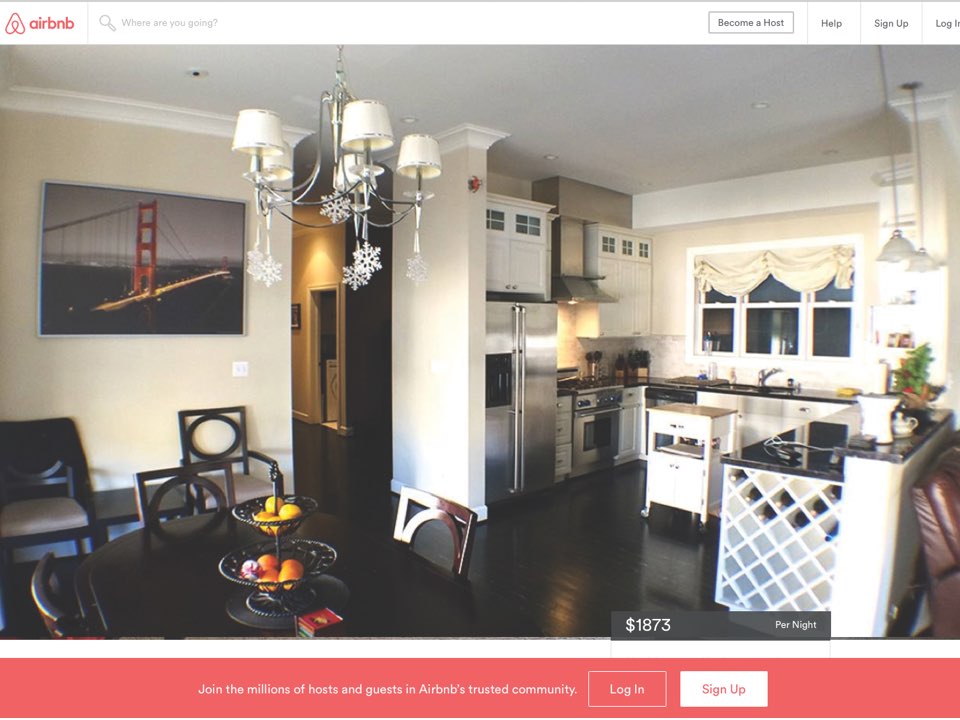

Of the 210 listings, only two displayed registration numbers, while more than 25 listings were standard hotel offerings. The cheapest listing was a studio on O’Farrell Street with a rooftop pool, available at $89 a night. The priciest was a three bedroom in Russian Hill, for $1,878 a day.

The cheapest room The Extra found, above, offered “pool+fitness downtown” for $89 a night. The priciest, below, is a “modern 3bd near Super Bowl City” for $1,873 per night.

The cheapest room The Extra found, above, offered “pool+fitness downtown” for $89 a night. The priciest, below, is a “modern 3bd near Super Bowl City” for $1,873 per night.

The city has initiated 349 short-term rental enforcement cases; nearly half remain open investigations. The office has closed 141 cases with a multitude of results: 46 cases involving 76 dwelling units were concluded with the imposition of fines. OSTR reports that it has assessed penalties of $692,728, but it has collected only $156,816. More than $535,000 in penalties remain unpaid, with half of that now in the hands of the Bureau of Delinquent Revenue, awaiting collection.

One major violator, Lumi Worldwide Inc., a Nevada corporation, was fined $191,000. Planning, acting on an anonymous tip, opened an investigation last year into the corporation’s renting of apartments at the Wilson Building on Market Street, where it holds leases on nine apartments. It was found to be renting them short-term to tourists and visiting executives from Fitbit, BMW and other corporations. (The Wilson Building offered five affordable housing units out of a total of 67 apartments when it opened for business in July 2014.)

Lumi Worldwide hasn’t paid the fine. Instead, it filed a lawsuit against the city, claiming a list of constitutional and evidentiary violations, including a lack of due process, in the city’s investigations. How an out- of-state corporation snagged multiple leases at the wilson in a city parched for housing remains unanswered. Raintree Partners, the Southern California developer that owns The Wilson, has not responded to the Extra’s inquiry on its relationship with Lumi Worldwide.

Guy is concerned about the low numbers of property holders seeking registration, but he’s not hesitant about using the powers conferred on his office. “We’ll continue our outreach efforts, and we’re looking to bring more traffic to our website, but at some point, we may have to concentrate more attention to enforcement,” he said. The vigor of enforcement efforts may be tempered by a political reading of the mood of the voters, who defeated Proposition F, a measure drawn up to tighten short-term rental laws, in November.

Guy’s office learns of possible violations of the short-term rental rules from a number of sources: homeowners' associations, neighbor complaints, Department of Building Inspection reviews, even call-ins to the Mayor’s Office of Housing. Some of the investigations have been opened as a result of his staff trolling the Internet and unearthing open violations of the law.

Short-term rental hosts operating without approval and registration can be fined up to $484 a day, from the date the city’s notice of violation is served to the date the unlawful rental is abated.

While the city proceeds slowly and methodically to bring seemingly reluctant hosts into compliance, others are clamoring for more immediate action.

The San Francisco Apartment Association, a nonprofit advocate for tenants and landlords, thinks short-term rentals are a “terrible idea,” citing a list of safety, building code, insurance and health concerns in recent notice to its members.

“We’re in a rent-controlled city,” said Charlie Goss, the association’s manager of government affairs. “Many people who are using this Airbnb opt-out are contributing to the serious housing shortage we now face. Why would any forward-thinking landlord want to hand the keys to his property to a stranger he knows only from the Internet? A good landlord wants to protect his tenants and his property.”

Goss was direct in placing responsibility squarely on the city. “I’m not surprised that so few have registered. Most of them can’t register. They’re not renting their primary residences, or they’re renting multiple units, or they’re corporations holding leases on many units—none of them could qualify. I think the absolute lack of strong enforcement by the city against illegal rentals is the real problem.”

Charisma Tompkins contributed to the research for this report.