When you go to the Contemporary Jewish Museum, located in what can now be considered the museum district (Yerba Buena Center for the Arts across the street, SFMOMA about to reopen, MoAD a block away, and the Mexican Museum relocating here in 2019), linger for a moment in the CJM’s spacious lobby before continuing on to the main exhibits.

There, in the lobby’s southwest corner, an installation, “Pour Crever,” stands, tall and quiet. Created by the German-born kinetic sculptor known simply as Trimpin, it is assembled partly of elements that resemble railroad tracks. The artist created this “fountain of memories” to memorialize the deportation of the Jews in his hometown, Efringen-Kirchen, to the detention camp Gurs in France.

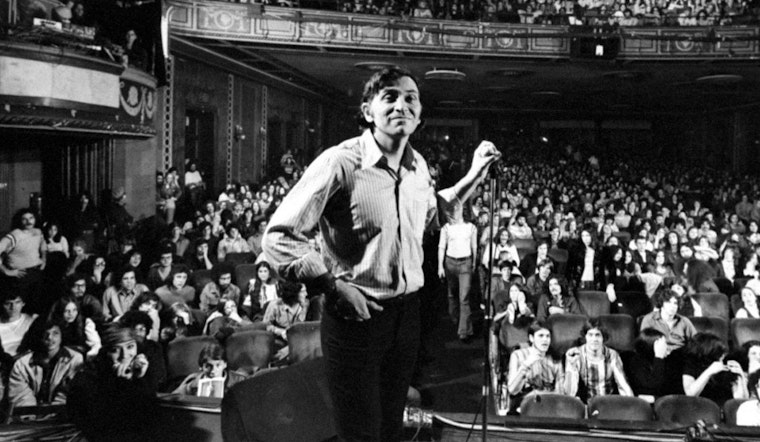

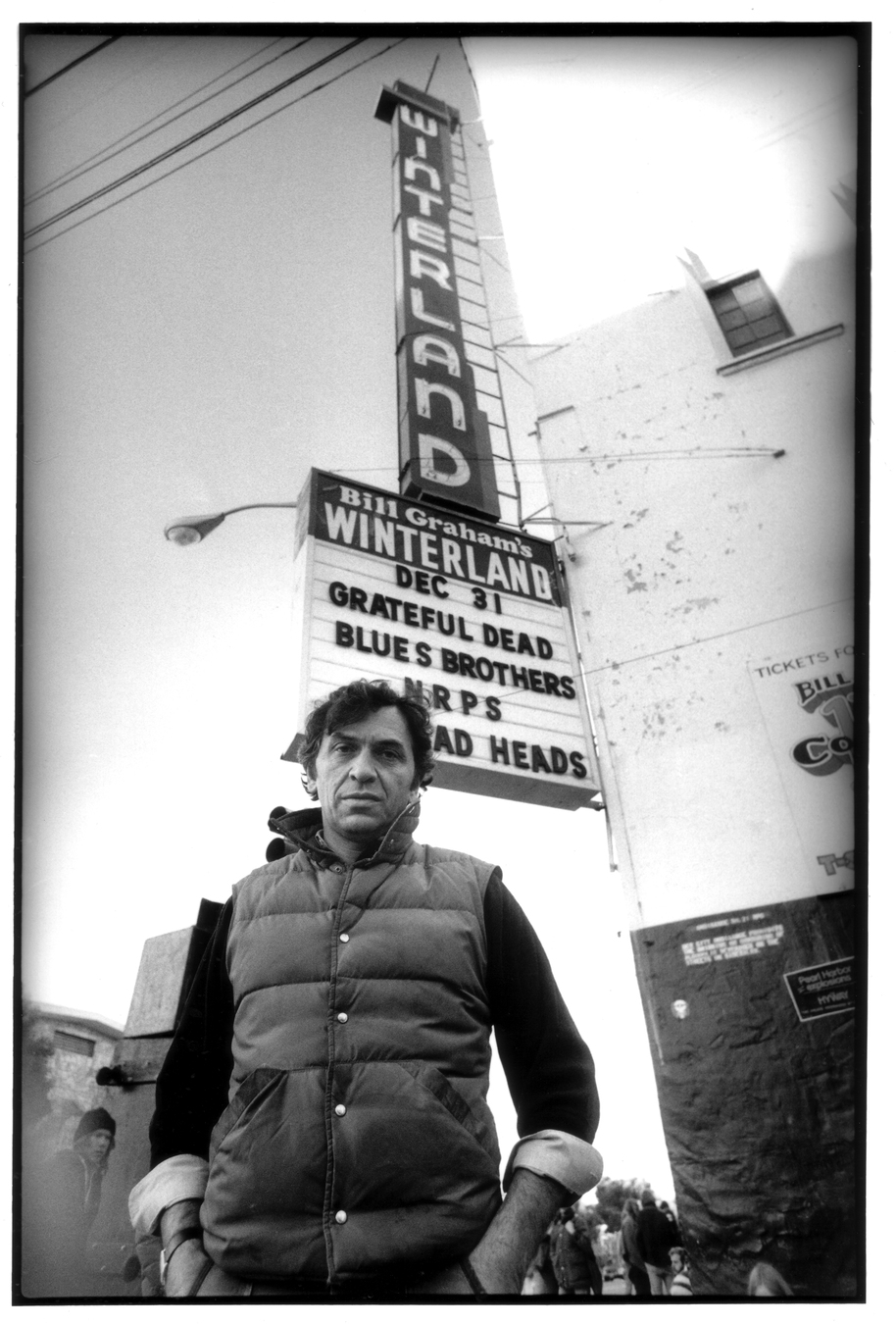

Photo: Michael Zagaris, Closing Winterland, December 31, 1978. Gelatin silver print, frame: 26 3/8 x 20 1/8 in. Courtesy of Skirball Cultural Center via CJM

Photo: Michael Zagaris, Closing Winterland, December 31, 1978. Gelatin silver print, frame: 26 3/8 x 20 1/8 in. Courtesy of Skirball Cultural Center via CJM

Each time you step onto a platform facing the sculpture, you are cueing a hidden computer to activate a tank of water at the top, which then releases a single, shimmering cascade that slowly spells out the name of a Jewish family of deportees. One by one, you can read the family names of all 300 residents as they fall, illuminated, through space and are swallowed up again in a tank at the bottom, fleeting and effervescent. Trimpin has said, “I cannot tell the whole story of Gurs, but I can tell a fragment.”

From Shtetls To Bill Graham

Since its founding in 1984, the CJM itself has been dedicated to telling fragments of the story of Jewish culture, ideas, and heritage. The museum has been housed since 2008 in an unusual building, designed by renowned architect Daniel Libeskind; it’s an “adapted re-use” of the red-brick-walled, 1907 PG&E substation that originally existed here.

Libeskind’s soaring extension to the building is based on Hebrew letters representing the phrase l’chaim (to life). Seen from the outside, the museum, with its blue metallic steel “skin,” is a unique blend of the old and the new, both physically and metaphorically. It fits with the CJM’s mission: “to bring together tradition and innovation in an exploration of the Jewish experience in the twenty-first century.”

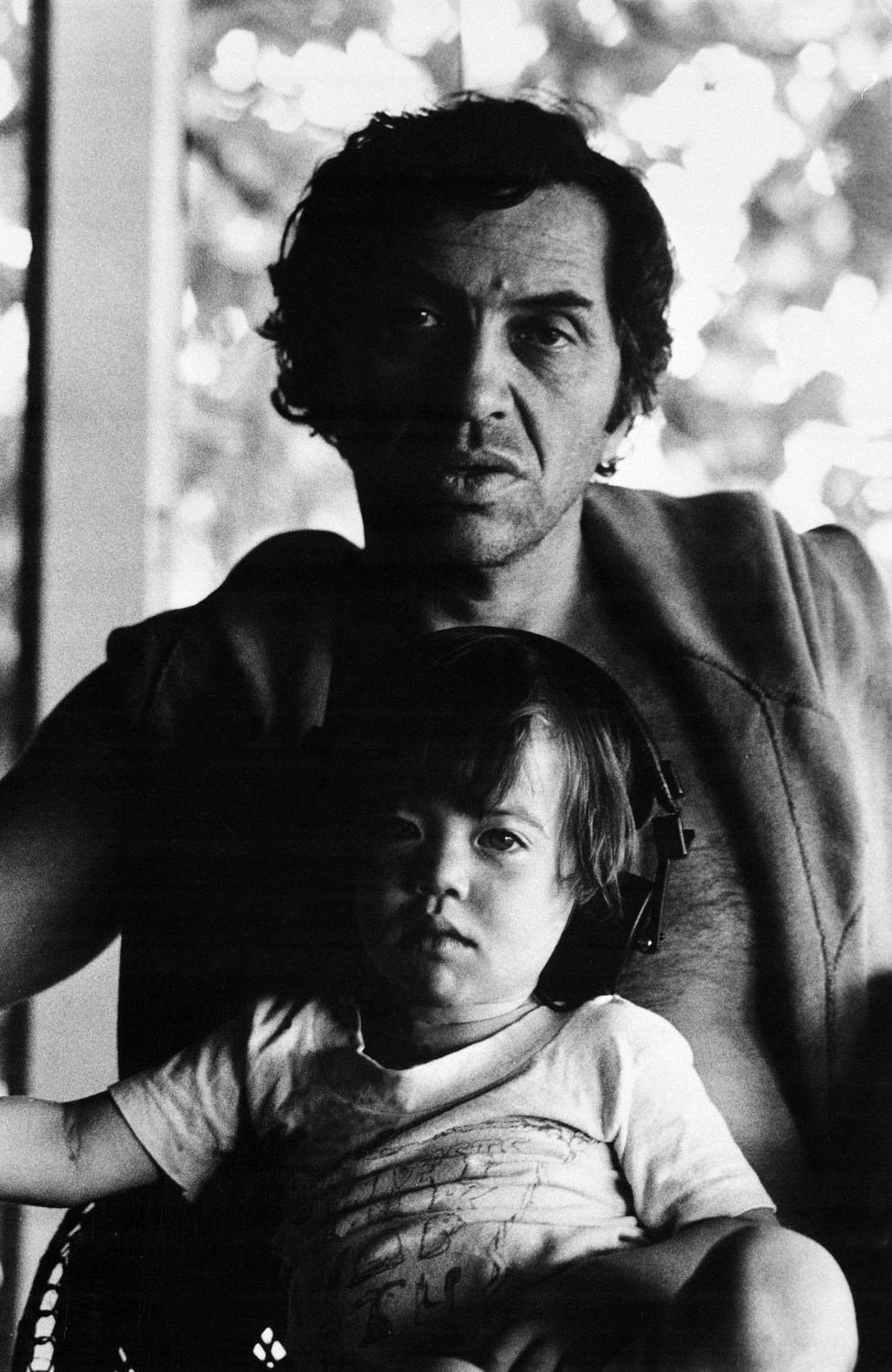

Photo: Marcia Sult Godinez, Bill Graham relaxes at home with son Alex., Marin County, CA, 1978. Gelatin silver print. Collection of David and Alex Graham via CJM

Photo: Marcia Sult Godinez, Bill Graham relaxes at home with son Alex., Marin County, CA, 1978. Gelatin silver print. Collection of David and Alex Graham via CJM

However, the CJM is not just for Jews. In fact, according to the museum’s demographics, half of its visitors are non-Jewish. Says executive director Lori Starr, “As a contemporary Jewish museum, the only one with this name, ‘Contemporary,’ we want to grapple with complexities of identity and diversity of the Jewish experience. . . . Because we’re a cultural institution we’re looking at Jewish culture and the things it has a common with other cultures—how it’s different, but more so the commonalities.”

Chief curator Renny Pritikin adds, “We are developing a strategy to address the spectrum of Jewish content in our exhibitions. Some are no brainers—a graphic history of shtetl life in Poland and Eastern Europe before World War II [as seen in the recently opened “Roman Vishniac Rediscovered”]. Then there are shows by artists who happen to be Jewish, which affords us the chance to interpret the Judaism in their work.

Or pop figures who are Jewish [a recent Amy Winehouse exhibit]. . . . The Bill Graham show [“Bill Graham and the Rock & Roll Revolution,” which opened March 17] is perfect. It gives us everything: popular appeal; it continues our music programming [which includes the ongoing “Hardly Strictly Warren Hellman”] . . . and it tells a Holocaust story which is certainly a part of the saga.”

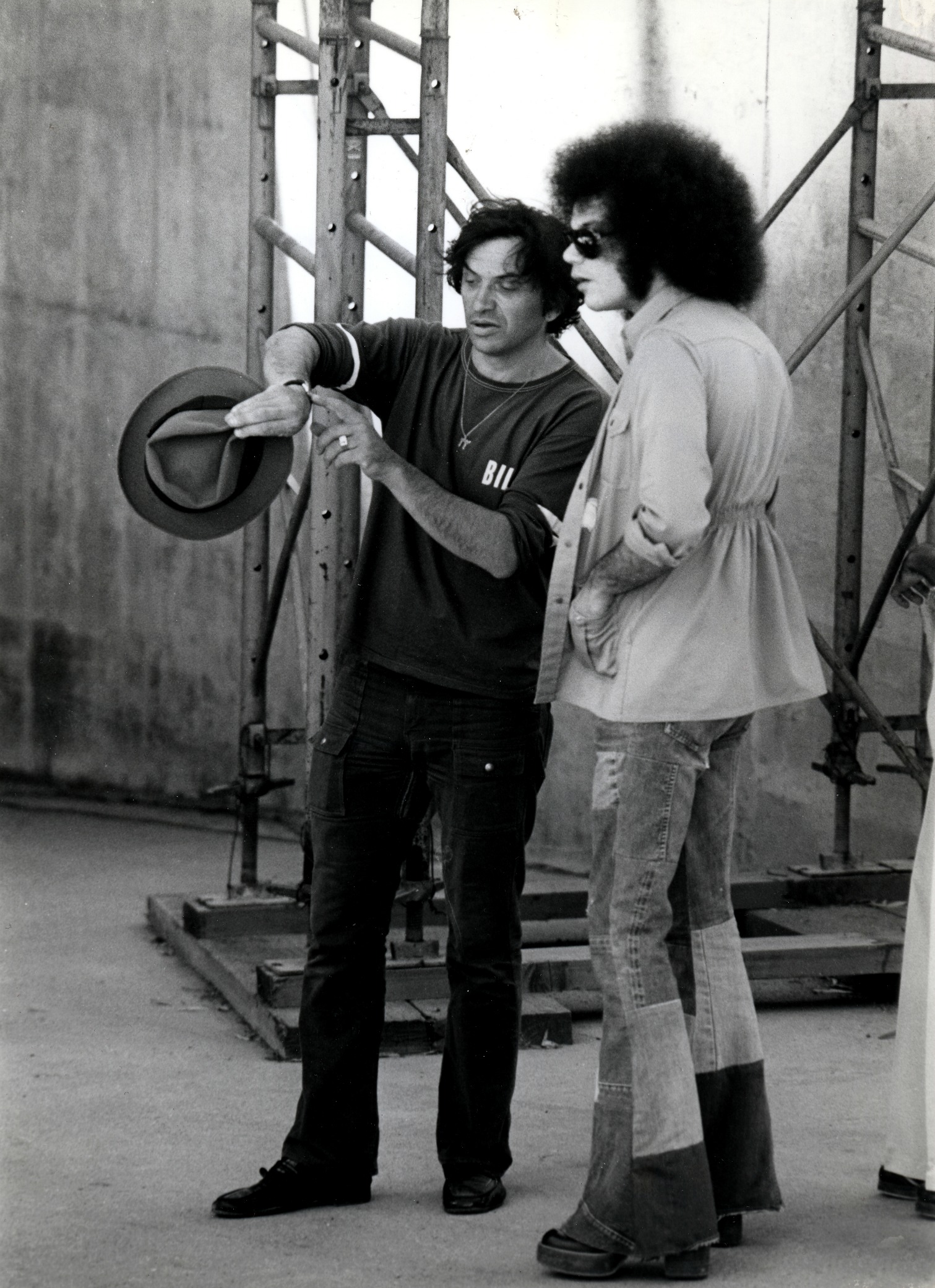

Photo: Robert Altman, Bill Graham enlightens Beach Boys Management: “Your band is late.”, Oakland Coliseum Stadium, Oakland, CA, June 1971. Chromogenic print. Courtesy of Robert Altman via CJM

Photo: Robert Altman, Bill Graham enlightens Beach Boys Management: “Your band is late.”, Oakland Coliseum Stadium, Oakland, CA, June 1971. Chromogenic print. Courtesy of Robert Altman via CJM

“Bill Graham and the Rock & Roll Revolution” is attracting those San Franciscans who, back in the day, attended concerts at Graham’s iconic Fillmore and Winterland, as well as a younger generation who may have never have heard of the impresario (1931-1991) who launched the careers of such groups as the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane and such stars as Janis Joplin and Carlos Santana.

Created at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles, it is the first major, comprehensive retrospective of Graham’s life, comprising 250 objects: photos of dozens of rock stars of the era plus personal and family photos; psychedelic-style posters; costumes (including Joplin’s feather boa); musical instruments; an audio guide with Graham himself talking; ephemera such as a 1966 dance hall permit for the Fillmore Auditorium; concert footage and audio interviews with musicians and celebrities; and other assorted memorabilia.

Photo: Roman Vishniac, [Vishniac’s daughter Mara posing in front of an election poster for Hindenburg and Hitler that reads “The Marshal and the Corporal: Fight with Us for Peace and Equal Rights,” Wilmersdorf, Berlin], 1933. Gelatin silver print. ©Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy International Center of Photograph, via CJM

Photo: Roman Vishniac, [Vishniac’s daughter Mara posing in front of an election poster for Hindenburg and Hitler that reads “The Marshal and the Corporal: Fight with Us for Peace and Equal Rights,” Wilmersdorf, Berlin], 1933. Gelatin silver print. ©Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy International Center of Photograph, via CJM

Much of the material, never before seen publicly, comes from the personal collection of Graham’s sons, David Graham and Alexander Graham-Sult. The exhibit includes the little-known story of Graham’s arrival in the United States at the age of 11 as a Holocaust refugee.

One of Graham’s lasting influences was in creating benefit concerts to support the humanitarian causes he cared about. Similarly, San Francisco businessman and philanthropist Warren Hellman (1934-2011) gave back to the community through the huge, free, annual Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival since 2001 in Golden Gate Park, which he set up to be funded in perpetuity.

The CJM’s ongoing “Hardly Strictly Warren Hellman” exhibit includes big-screen video clips from some of the festivals, featuring such artists, beloved by Hellman, as the late Hazel Dickens, Emmylou Harris, and Ralph Stanley. It also includes photos, listening stations and memorabilia: Hellman’s rhinestone studded jacket, signed banjo, and more.

Photo: Roman Vishniac, [Preparing food in a Jewish soup kitchen, Berlin], mid–to late 1930s. Gelatin silver print. ©Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy International Center of Photography via CJM

Photo: Roman Vishniac, [Preparing food in a Jewish soup kitchen, Berlin], mid–to late 1930s. Gelatin silver print. ©Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy International Center of Photography via CJM

Particularly dazzling is “Roman Vishniac Rediscovered,” an extensive exhibit, running through May 29, that covers five decades of work by the Jewish immigrant to New York (1897-1990) who is best known for documenting the soon-to-be-annihilated Jewish community of Eastern Europe before World War II.

But Vishniac, says curator Maya Benton, is not just a great Jewish photographer; he is one of the major modern photographers—more versatile than ever realized. He was a pioneer in the field of color photo microscopy (with a particular interest in photographing insects); he was an urban photographer who captured sensitive and revealing pictures of, for example, Berlin before and after the war, and the Jewish and other communities in Europe and New York post-war.

On assignment as a photojournalist between world wars, he captured scenes of abject poverty in the rural Jewish communities of the Carpathian mountains; and he was a portrait photographer whose subjects included such celebrities as Albert Einstein. The exhibit, created in 2013 at the International Center of Photography in New York, includes vintage prints, film footage, personal correspondence, books and ephemera--almost 400 objects, many of them never before seen. The sheer historical and geographical scope and compositional artistry of this exhibit make it a must-see.

The CJM, 736 Mission St., daily 11am–5pm, Thursdays 11am-8pm, closed Wednesdays, 415.655.7800, |[email protected].

-1.webp?w=1000&h=1000&fit=crop&crop:edges)