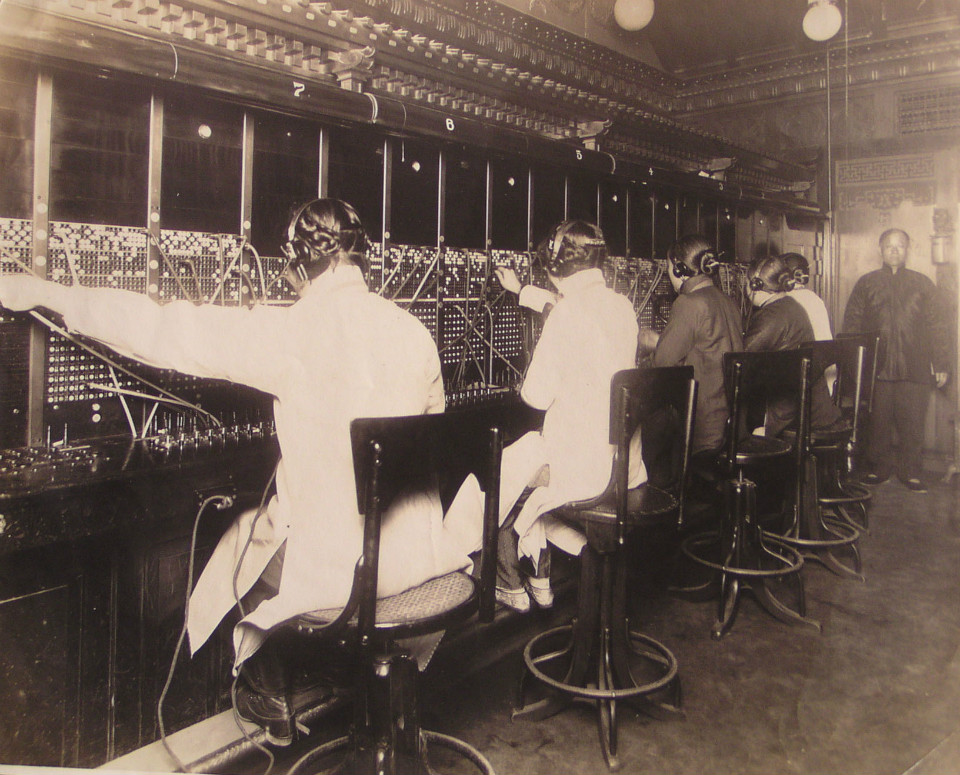

It's hard for many people today to imagine a life without cell phones, but in the early days of telephone technology, callers couldn't even directly dial numbers—they called up an exchange staffed with operators, who would manually patch them through to the other party with wires they plugged into a switchboard.

One of the most famous telephone exchanges was in the heart of Chinatown, at 743 Washington St. (These days, it's an East West Bank.) According to an article in the April 10th, 1936, edition of the weekly Chinese Digest, the Chinatown Exchange—also called the Chinese Telephone Exchange in some sources—began in 1894. It had three male operators and 37 telephone subscribers, all within Chinatown.

Although some accounts say the exchange started in 1887 or 1901, the 1894 date is corroborated in the book Bridging the Pacific by Thomas Chinn, one of the founders of the Chinese Historical Society of America. Chinn says a man named Loo Kum Shu—editor of one of Chinatown's first Chinese newspapers, the Oriental Daily News—established the first exchange.

743 Washington St. today. (Photo: Geri Koeppel/Hoodline)

According to Chinn's book, the first switchboard in Chinatown was in a building at Washington and Dupont streets (the latter of which is now Grant Avenue). In 1896, the Chinese Digest article says, the exchange moved into a permanent home at 743 Washington, the former site of Sam Brannan's California Star, the first newspaper in San Francisco. (In January 1847, the Star published the city's official name change from Yerba Buena to San Francisco.)

The Chinese Digest writes that the original exchange at 743 Washington was unrivaled in its beauty by any other local business at the time:

Its exterior was remodeled and furnished in such a sumptuous Oriental manner as to suggest a guest room in the house of a mandarin of the first rank. There were chairs of carved teakwood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl; bright-black, glistening teakwood tables; gilded and lacquered carvings abounded on every side; the windows were of imitation Chinese oyster-shell panes. And near the entrance was a beautiful shrine, giving the place a touch of religious splendor. The switchboard, too, was elaborately designed, made of ebony and ornamented with woodcarvings of yellow-gold hue. A carved dragon seemed to wind its sinuous way in and out of the plug-holes.

Chinese Telephone Exchange, c. 1902. (Photo: Courtesy of Philip Choy)

Alas, this exquisite exchange was destroyed by the great earthquake and fire that occurred 110 years ago today: April 18th, 1906. The three-tiered, pagoda-style building that remains on the site to this day went up in 1909, serving 800 phones. "Patterned after a temple in North Lake, China, the corners of the building turn up, to give it 'lofty character', while the sturdy pillars in front 'denote the strength' of the building," according to the Chinese Digest.

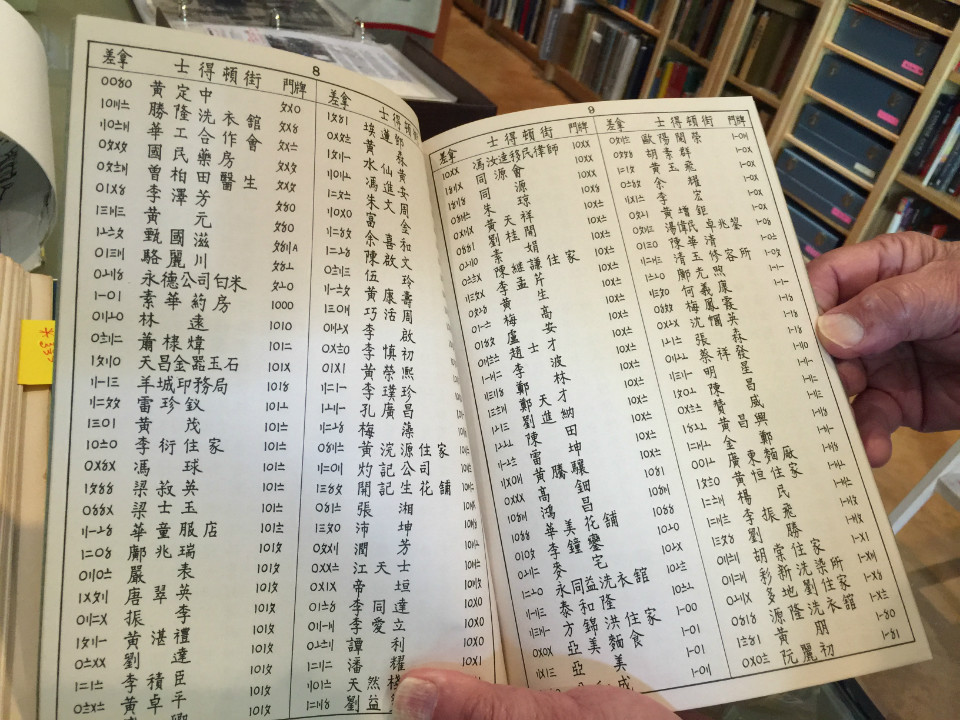

After the earthquake, the staff of the Chinese Telephone Exchange became all-female. To work on the exchange, operators were required to be able to recall, completely from memory, thousands of phone numbers—at its height, the exchange had more than 3,000 of them. Callers would ask an operator to be connected to an auntie, or the local herb shop, or their eye doctor. The women knew names, addresses and workplaces for all the subscribers, and could speak in two or three different dialects.

Photo: Courtesy of Lana Chong

Some accounts, such as one in City Walking Guides, say this is because "it was considered impolite to use a number when referring to a person," but those we interviewed said that wasn't true. “Most of [the callers] forgot the numbers, so they just named the subscriber," said Dr. Alfred Lee, whose mother, Choy Chan Lee, began working at the exchange during the 1910s and was employed there until it closed in 1949.

Lee, who is nearly 96, still can be found helping out at the optometry shop he started in Chinatown, at 748 Sacramento St. These days, it's run by his son, Michael.

Video of Dr. Alfred Lee by the Chinese Historical Society of America. (Source: YouTube)

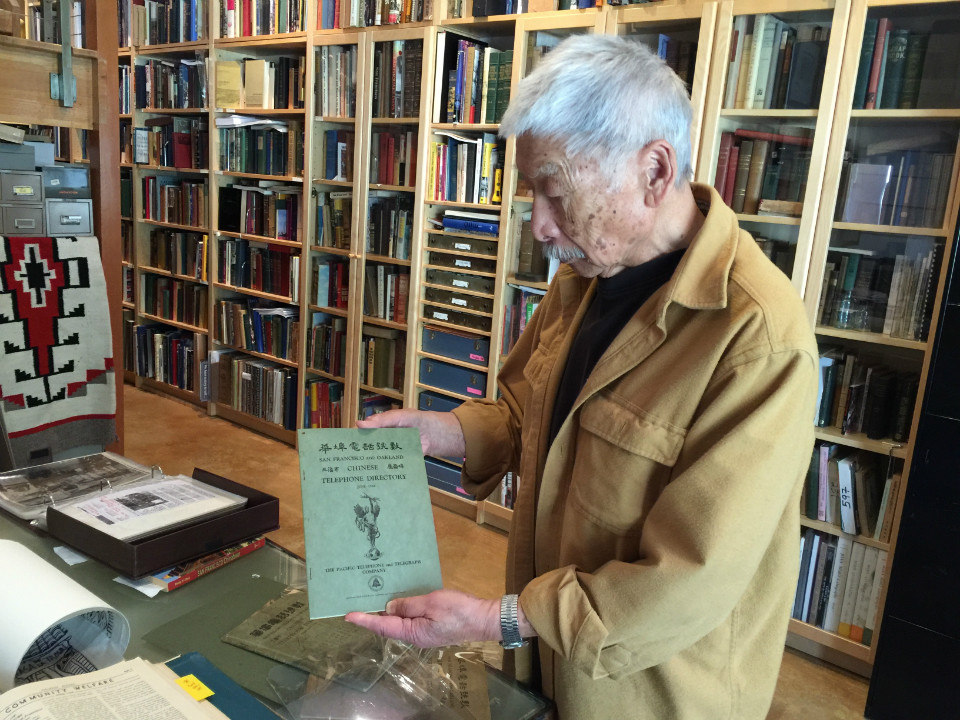

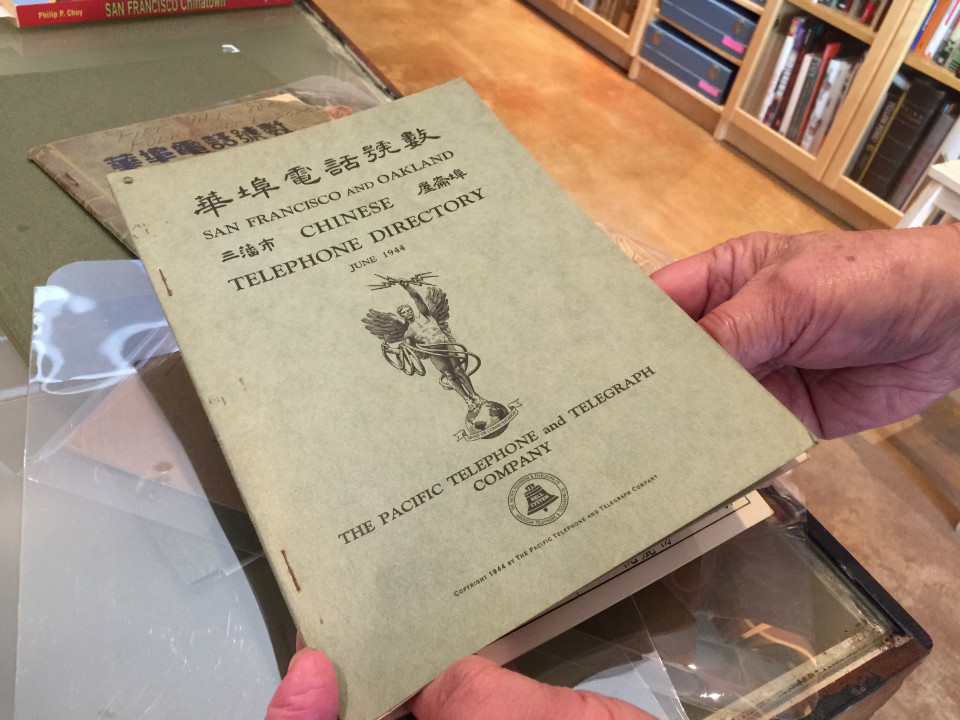

Philip Choy, 89, a retired architect who taught Chinese-American history at San Francisco State University, told us the same—people would call up and not know a number. "By habit, the telephone exchange did recognize and memorize everybody’s subscriber. That’s what they claim. They also remember the most popular store names."

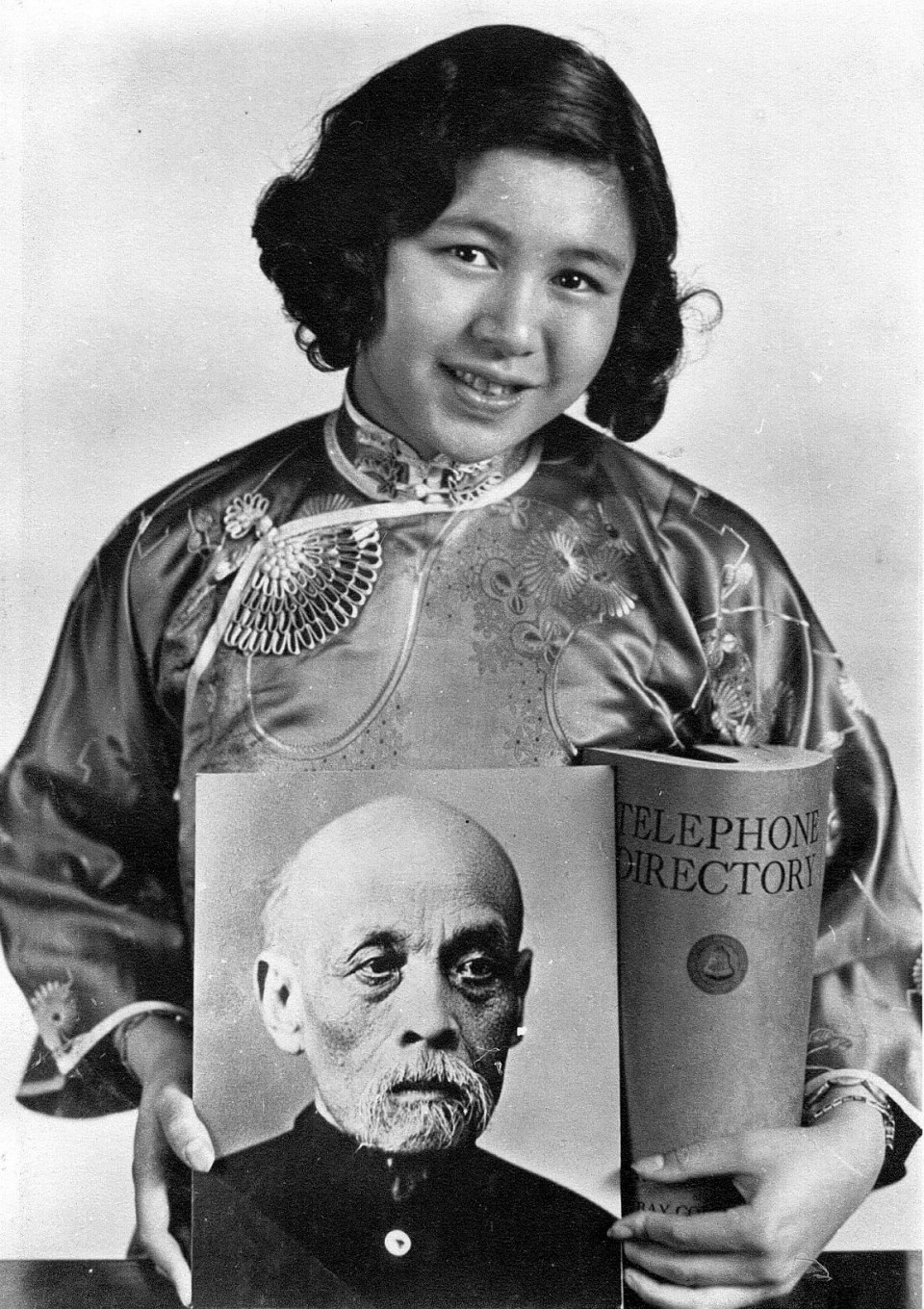

Choy showed us some of the era's phone books, which were hand-written in Chinese characters by a calligrapher related to one of the managers, he said. He still remembers his phone number, 1068, and his aunt's, 1965.

Philip Choy displays phone books from the 1940. (Photos: Geri Koeppel/Hoodline)

At the time, Lee and Choy told us, the exchange was a major tourist attraction. Lee said Greyhound buses would pull up, and tourists would get out and go to the window. He would pull aside a curtain to reveal the stylish female operators, clad in embroidered silk dresses.

"It was a place that was somewhat exotic, you might say," Choy told us. "[At the time], it was strange to see Chinese women sitting there, speaking Chinese over the telephone."

Photo: Courtesy of Lana Chong

Lee spent a lot of time at the exchange because his father left when he was very young, and his mother raised him as a single parent. He even recalls the layout of the room, described in detail in this November 17th, 1901 article from the San Francisco Examiner on the Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco website. (One politically incorrect line: "The Chinese telephone company was to put in girl operators when the exchange was retrofitted, and doubtless it will be done eventually. The company prefers women operators for many reasons, chiefly on account of good temper.")

Though the article goes on to say the price for women would be too high because they'd need to be "purchased outright," a facetious—and prophetic—general manager was quoted as saying, "but in the next century, we'll be able to afford them, for girls will be cheaper then."

Photo: Courtesy of Lana Chong

Indeed, the women weren't paid well, Lee said, and his mother was hard-pressed to house and feed him. "Instead of being homeless, we bounced from family to family, wherever they had space," Lee said. "We paid them rent for one room." Sometimes, he lived in a cabinet, he said, laughing. Dinner was often one egg, cut in half, over rice. And after a lifetime of service, his mother got a pension of about $40 a month.

According to an article on FoundSF.org, in 1943, the 30 workers joined the Telephone Traffic Employees Organization (TTEO) Local 120. "They fought their seven-day-a-week work schedule, filing complaints with the War Labor Board and winning back pay of $5,000 as well as overtime pay," it says.

Life at the exchange wasn't all bad, though. It was a social hub, because the women were all around the same age and grew very close. Many even had babies around the same time, and posed for a photo with their children.

"It was a safe haven," Lee said. "They worked eight or 10 hours. The job was not tedious—they were busy hours." His mother became so close to the other workers that she considered them to be like sisters, he said.

Telephone exchange babies, 1937. (Photo: Courtesy of Lana Chong)

Many of the women actually were related—some of them got jobs because their fathers or grandfathers worked at the exchange from the time it was founded. "Today, you would call it nepotism," Lee said. But in those days, work was hard to find, so people who had jobs helped out their families.

Lana Chong of Sacramento, wife of Elvin Chong, noted that several generations of family members worked at the exchange. Elvin's great-grandfather, Chan Yung Lai, worked there, and taught his daughter, Ho Chan Lee, to operate the switchboard. She retired in 1935 after 25 years of service, and her daughter (and Elvin Chong's mother), Elizabeth Lee Chong, took her place. Alfred Lee's mother, Choy Chan Lee, was the sister of Ho Chan Lee. "As the other operators retired," Chinn's book says, "their daughters also took their places."

Elizabeth Lee Chong, c. 1936-38. (Photo: Courtesy of Elvin and Lana Chong)

Left to right: Unknown woman, Elizabeth Lee Chong and Ho Chan Lee. (Photo: Courtesy of Lana Chong)

Long before the advent of Amazon and DoorDash, the telephone exchange had also hipped the Chinatown community to delivery services. By 1911, the exchange had 474 business subscribers and 600 residential subscribers, the Chinese Digest article says, and Chinese women would do their shopping over the phone. Restaurant delivery boomed, too.

By 1936, the exchange had 21 operators for 2,200 phones in the community, including businesses, residences and public phones. In all, Lee told us, Chinatown had about 3,000 numbers by the time it closed in 1949, after dial phones were introduced. (It was taken over by Pacific Telephone and Telegraph.)

But the exchange still lives on for film noir fans: it figures as a prominent plot point in the 1949 movie Chinatown at Midnight. We won't spoil it for you.