Many San Franciscans turn a blind eye to homelessness on the city's streets, but for one class of undergraduate architecture students at the Academy of Art University, that wasn't an option. Instead, their professors forced them to dig deep into the needs of the Tenderloin's homeless people and service providers, designing shelters that could better serve the neighborhood.

Professors Doron Serban and Sameena Sitabkhan explained that every semester, their students are tasked with designing a public-private development. They've previously worked on schools and fire stations, but this was the first time they've tackled homeless shelters.

The professors decided to have the students work on a fictional concept for the former Hollywood Billiards space at 1028 Market St., which The Hall is currently occupying as it awaits demolition. (In reality, it's set to be developed into a mixed-use residential building with 186 units.)

Serban and Sitabkhan chose the space because it lies at the border of investment-fueled Mid-Market and the historically low-income Tenderloin. "We've got one side facing Golden Gate, where there's lots of nonprofit and homeless providers and soup kitchens, and the other side is Market, where a lot of tech companies have moved in and gentrification is going on hardcore," Sitabkhan said. "The students are to bridge the two populations, and try to create a building that represents a new model for what a homeless shelter could be."

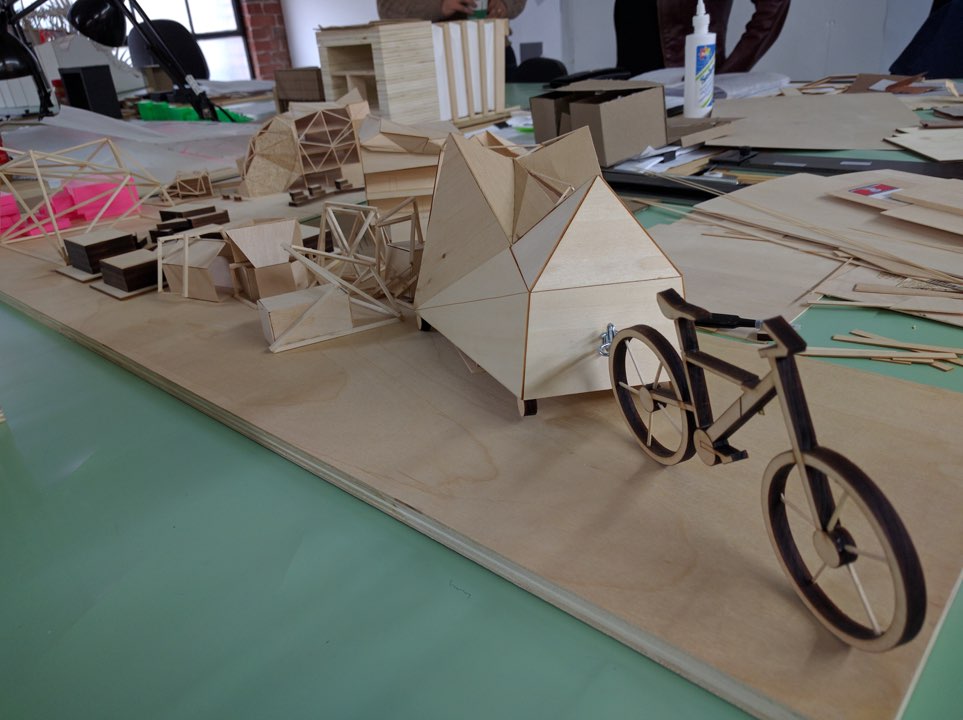

Using wood, the students created a model of the entire Tenderloin. 1028 Market St., the site they took on, is blank.

One of the project's first steps was interviewing homeless people on the streets of San Francisco, to learn more about their needs and design an individualized shelter they could use nightly.

"The premise to that was to design a portable sleeping unit for someone, specific to that person's situation," Serban said. "We called it 'improvised guerrilla sleeping units,' and the idea behind that is it doesn't have to be a city-mandated-type thing."

"One of the big things in architecture school is to not make things super-generic and design from 60,000 feet, but to get students to understand that there's a population," Serban continued. "Fire stations are easy to get students to engage, because everybody loves firemen. But to really give the homeless the respect they deserve, we asked them to actually talk to them. Heaven forbid, make eye contact! Better yet, have a conversation and understand they're a person."

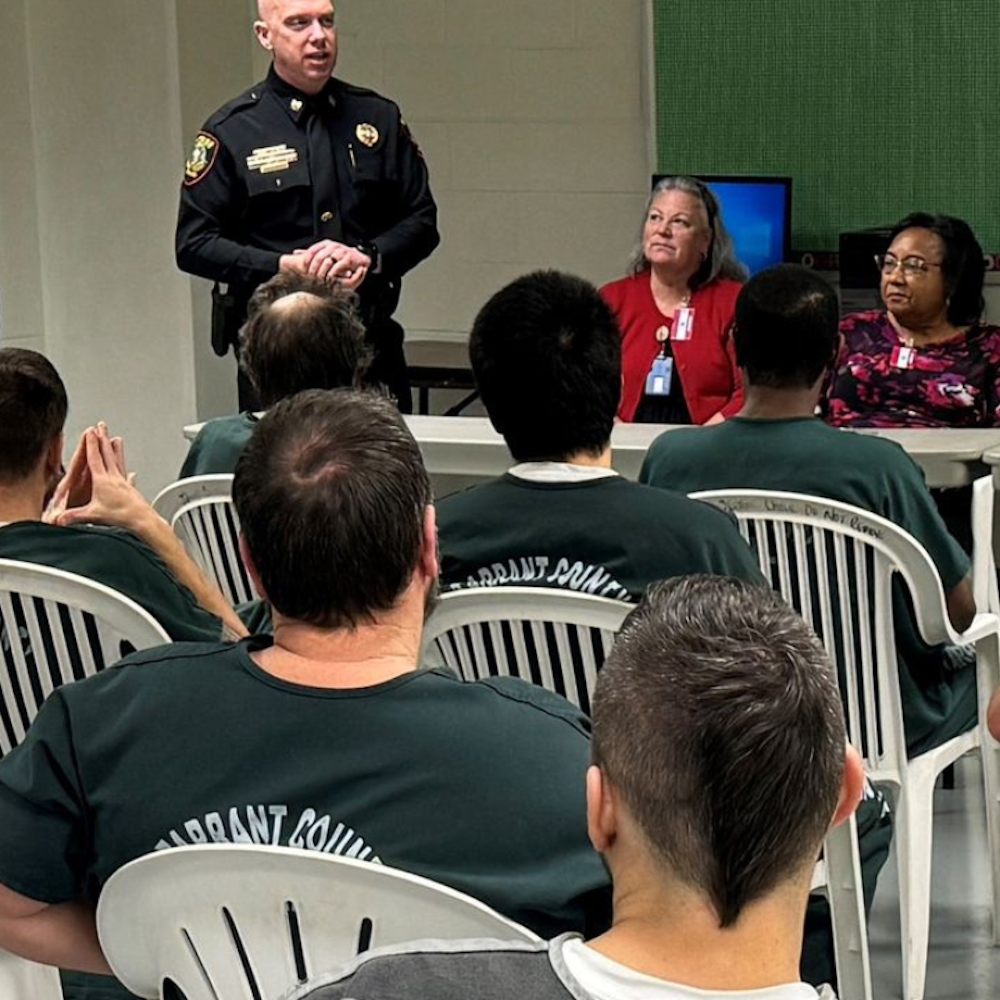

To further prepare for the project, the class took a tailored Tenderloin Walking Tour with Del Seymour to explore the neighborhood's homeless-serving nonprofits, took part in a lecture by a homeless outreach coordinator at Community Housing Partnership, and met with a landscape architect to better understand the importance of outdoor space for both the overall population and their specific location.

Along the way, they learned some important lessons. "I think when we started, very early on, we had some very generic ideas—all of us, including me—about who is homeless and why're they're homeless. And by the end of it, I think a lot of students had changed their tune. The interviews and the first-hand experiences really helped," Sitabkhan said.

One of the preconceived notions the students' interviewees and lecturers dispelled was the idea that homeless individuals would rather live on the streets than in a shelter.

"For me, that was the most interesting, because everyone was like, 'A lot of homeless people don't want to live in a place. They want to be on the streets, because they have freedom, and they don't want to go into shelters,'" Sitabkhan said. "And then we had a speaker come in and say, 'Of course they don't want to go into shelters; they're dangerous and scary and horrible places. If you can stay out on the street in the fresh air, even though you're freezing, you'd rather do that, because you can have your own safety zone.'"

Using their research, the students proposed a community engagement component that would bring together the neighborhood's unhoused and housed populations, and expanded the idea behind their 'improvised guerrilla sleeping units' into large-scale public-private homeless shelters. A few of their suggested community engagement components included a doggie day care center, an animal clinic, a dance-therapy center for sex workers, an obstacle course and a culinary school.

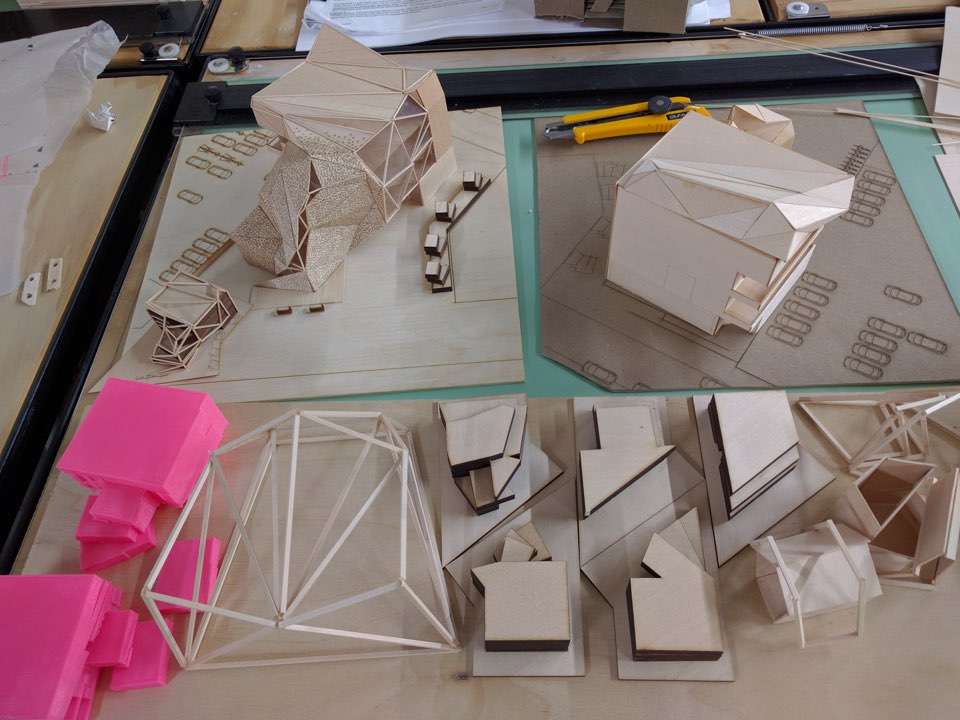

The idea for a private homeless shelter (above) transformed into one for a public homeless shelter (below).

The idea for a private homeless shelter (above) transformed into one for a public homeless shelter (below).

The homelessness assignment came as a surprise to the students, who thought they'd be working on public schools, and came into the semester with ideas already in mind. Sitabkhan and Serban said that it's been fun to watch their largely international class get to know the city, and what's going on outside their classroom.

"The first day of class, we asked, 'Who walked by a homeless person today?'" Serban said. "Almost everyone raised their hand. And then we said, 'OK, who looked at a homeless person?' and only about half raised their hands. 'Who said hi?' No one. It's been wonderful to see students wake up, in a way, to what's going on around them." He noted that having Super Bowl 50 unfold in the middle of the semester, creating further debate around homelessness in the city, was quite fortuitous for the student learning experience.

One student, Fernanda Kanamori, said her whole project—a homeless shelter with a prenatal clinic—was based on the experiences of a friend's formerly homeless mother, whom she interviewed. In addition to learning about and designing for homeless pregnant women, she said the experience became deeply personal, because she was designing the shelter with a specific person in mind.

Another student, Kathleen Agonoy, agreed. "I'd never been to a homeless shelter until we went on the museum tour, so it was a really eye-opening experience ... They're everywhere in the city, but you never really interact with them."

Agonoy ended up designing a homeless shelter with an integrated transgender health clinic, as she learned that the Tenderloin is home to many transgender residents. "I thought maybe they should have a place to call their own," she said, citing the current debate over which gendered restroom transgender individuals are legally allowed to use. In her shelter, Agonoy created suites that each accommodate four residents, and include one unisex bathroom to share.

For the next month, the Tenderloin Museum will display the neighborhood model the class built, along with their shelter prototypes, books detailing their design processes, and other artifacts documenting the project. All are welcome to join the class this Friday, May 13th for an opening reception.