100 years ago today, July 22, 1916, a parade down Market Street intended to drum up support for America's entry into World War I was interrupted by a bombing that ultimately killed 10 people and injured 40. Although two labor activists were quickly arrested, tried and convicted for the crime, consensus soon grew that they'd been railroaded. In time, both men were exonerated, leaving the Preparedness Day bombing as the city's oldest unsolved mass murder.

In the summer of 1916, European powers were waging war in trenches and on the seas of the North Atlantic, but America remained neutral. Focused on pushing his New Freedom platform of progressive reforms, President Woodrow Wilson recognized that a war would hijack his ambitious social agenda.

Wilson ran for re-election on the slogan "He Kept Us Out of War," and Americans whistled along with a pop song called "I Didn't Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier." But there was a rising call for the U.S. to begin marshaling wartime resources. Led by former president Theodore Roosevelt, military experts and a cadre of bankers and manufacturers, the Atlanticists were the progenitors of what would later be known as the military-industrial complex.

The Atlanticist position: while idealism was fine, America needed to gird itself with a strong navy, a sizable land army, and the infrastructure necessary to produce enough armament to protect the homeland, just in case. At the time, the U.S. had a standing army of just 100,000 troops, with a similar amount of National Guard soldiers.

Eventually, events forced Wilson's hand; the German navy was practicing unrestricted submarine warfare to stop American supplies from reaching its enemies. In March 1916, Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa burned Columbus, New Mexico to the ground in a cross-border raid that kicked off a fruitless month-long campaign aimed at his death or capture. Interventionists now had clear evidence of America's weakness.

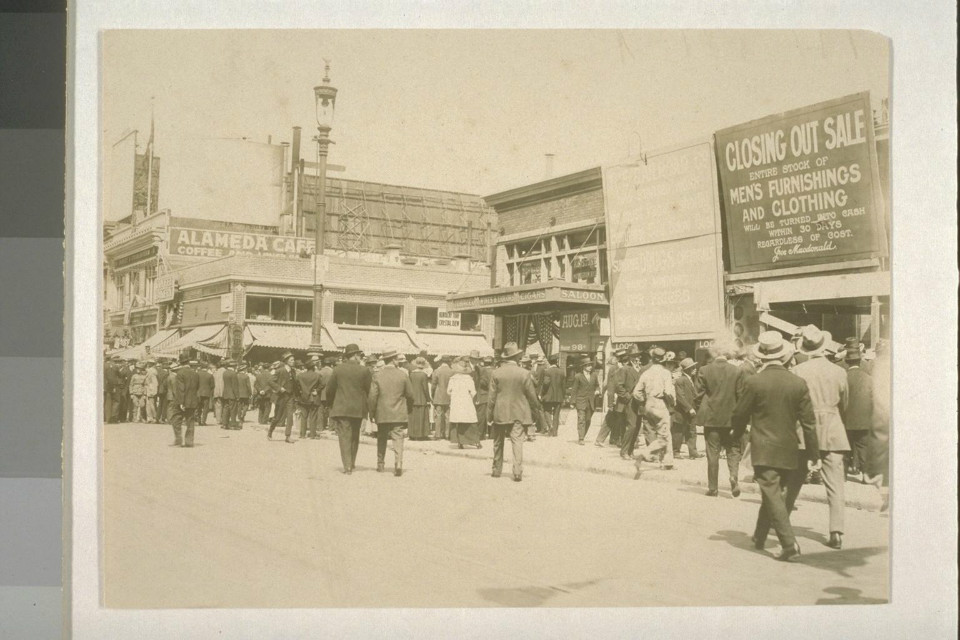

By May 1916, New York and Chicago had rallied their citizenry to support a wartime build-up via preparedness parades. San Francisco's procession was organized by the Chamber of Commerce and other business interests, but there was still a strong isolationist streak. On the eve of the parade, mainstream and radical union leaders met at Dreamland Rink, a roller-skating palace at Post and Steiner, to denounce the celebration.

"The viewpoint of all those who spoke was that the preparedness propaganda is being carried out for ulterior purposes, and that it makes for a serious menace to the ideals of world peace," reported the San Francisco Chronicle. "Those present were advised to stand silent as the paraders passed."

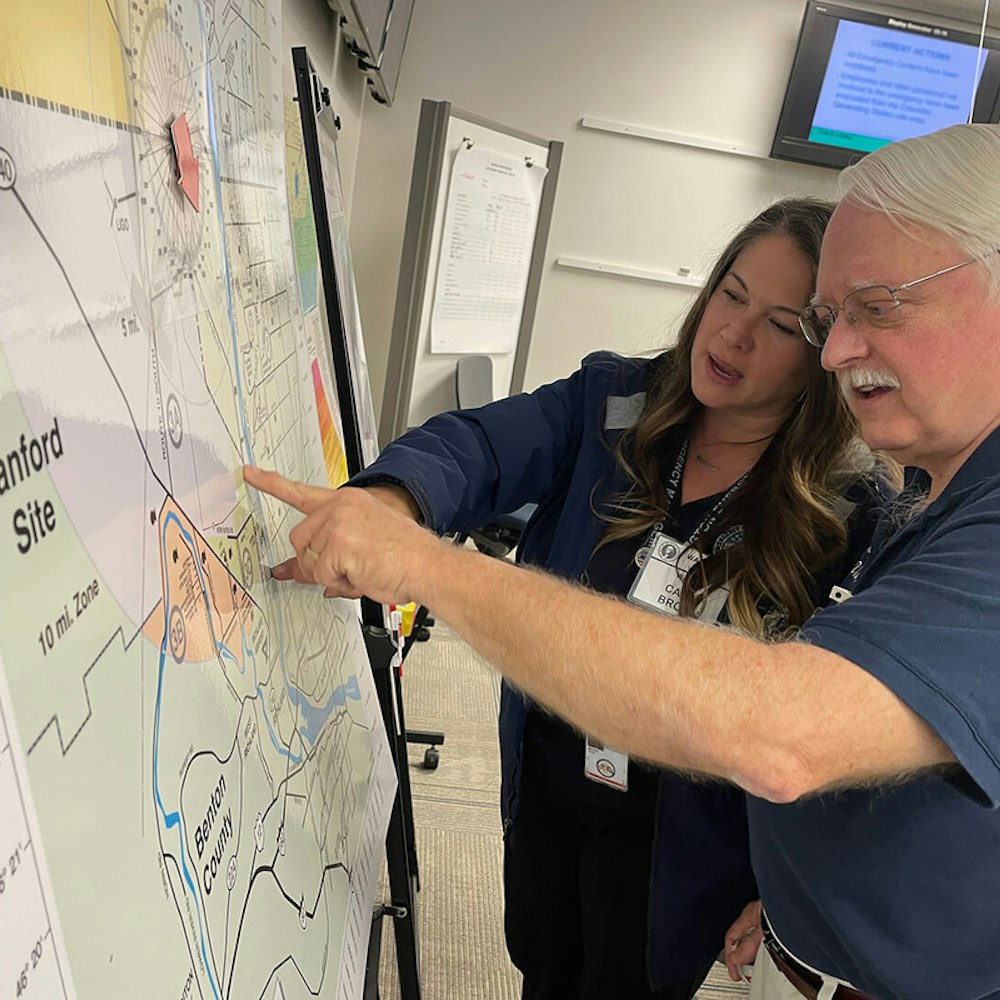

On the morning of July 22, 115 divisions formed up at the Ferry Building for a 3.5-hour march that ended at Van Ness Avenue. More than 50,000 people, representing the Bay Area's business, civic, and municipal sectors, formed neat rows, along with divisions comprised of active military and citizen militias, as well as white-collar employees from area streetcar, telephone and telegraph companies.

Many prominent parade supporters received warnings before the parade. City Treasurer John McDonald reportedly carried a pistol after receiving a note informing him that "the immediate extermination of you is going to be a sole and patriotic duty."

Shortly after the parade kicked off at 1:30pm, Mrs. William Hinkley Taylor, a pro-preparedness socialite, told officials that a "rough-looking man" passed her a note with a bomb threat. She crumpled the paper, then joined the procession.

About 30 minutes later, at 2:06pm, an explosion tore through the crowd near Market and Steuart. When the heavy smoke cleared, bystanders were presented with a horrific tableau. Blood flowed freely in the gutters; bodies of the dead and dying lay in heaps, many missing limbs. Police determined that the destructive device was a pipe bomb packed with explosives and metal slugs, set off with a timer.

Incredibly, after pausing to allow marching veterans to attend to the injured and delivery trucks to support overloaded ambulances, the parade resumed.

Police conducted a cursory investigation before rounding up likely suspects from the local labor movement. In short order, organizer Thomas Mooney and his assistant, Warren K. Billings, were charged with staging San Francisco's deadliest terror attack.

Local papers printed horrific details from the scene for days, stoking anger against unions and agitators who'd opposed the parade. Newsreel producers Hearst-Pathé used film footage of the bombing's aftermath to produce a propaganda film urging San Franciscans to choose "prosperity" over "anarchy, sedition and lawlessness."

Mooney and Billings were tried separately. Even though neither man fit eyewitness descriptions of the bomber, and a photo taken minutes before the bombing showed Mooney watching the parade from a vantage point more than a mile away, both were convicted and sentenced to death.

In 1917, Woodrow Wilson convened a commission that took a fresh look at the trials, since supporters had unearthed compelling evidence of the two men's innocence (along with suborned perjury). "We find in the atmosphere surrounding the prosecution and trial of the case ground for disquietude," the commission reported. The two men had their sentences commuted to imprisonment, and in 1939, California Governor Culbert Olson pardoned them.

For years, historians have spun various theories about the parties responsible for the Preparedness Day bombing. Officially, however, the crime remains unsolved.

LaborFest, a nonprofit group that preserves the history of organized labor, stages a cultural festival each July to commemorate the Preparedness Day Bombing, as well as the San Francisco General Strike of 1934.

Tonight at 7pm, writer and historian Steven C. Levi will present "The Lessons of the Preparedness Day Bombing for Today: Repression, Frame-up, Labor and Political Prisoners," a talk that examines the events that led up to the bombing, as well as its impact on the City's labor movement. There's no cost to attend the forum, which will be held at ILWU Local 34 Hall at 801 2nd St.

Tomorrow morning at 10am, Levi will lead a two-hour walking tour that includes several sites related to the bombing and the labor movement at the turn of the 20th century. Interested parties should gather at 1 Market St.; attendance is free.