[Editor's Note: Mark Ellinger is a Tenderloin-based photographer and writer who documents the central city at his blog Up From The Deep. In his chronological history of the Tenderloin, excerpted below, he shares his personal perspective of the uptown segment of the Tenderloin as he's seen it change over the years. You can find the full entry here.]

A Brief Introduction

The architectural data in this section was first researched over twenty-five years ago by the late Anne Bloomfield, and more recently—in depth and with meticulous attention to detail—by Michael Corbett, with whom I worked in 2007-8 on a survey of the Tenderloin for the National Register of Historic Places district nomination. Historical details have been drawn from my own research and personal experience, as well as the painstaking research of friend and fellow historian Peter Field, who each spring and fall gives free historical walking tours of the Tenderloin, which I highly recommend to all.

Prior to the establishment of the Uptown Tenderloin Historic District in 2009, the Tenderloin was never an officially adopted district, but rather, an informal and popular area designation, having no precise boundaries. A complex area linked to well-defined districts on every side, its eastern and northern boundaries in particular were impossible to pin down, and the common name for the area—Tenderloin—did not appeal to the real estate or hotel industries, or to middle class residents.

Largely developed as a respectable residential area, it was home to socially ambitious people before the 1906 fire; afterward it was rebuilt for retail and office workers. Yet for over a century it has been best known as the Tenderloin, a center of both legal entertainment businesses including theaters, restaurants, bars and clubs, and illegal businesses for the accommodation of vice—prostitution, gambling, Prohibition-era drinking, and drugs.

Early Development

In the years just prior to the California Gold Rush, the vicinity of what would later be known as the Tenderloin was an undeveloped area with low sand dunes rising along the southern flank of Nob Hill. When the United States began its conquest of California in 1846, Lieutenant Washington Allon Bartlett, USN was first appointed and then elected as the alcalde (mayor) of the trading hamlet of Yerba Buena.

Believing that marrying the town’s name to that of the San Francisco Bay would give them a commercial advantage, its merchants and tradesmen prevailed upon Bartlett, and on 30 January 1847, he issued a proclamation that officially changed the name of Yerba Buena to San Francisco.

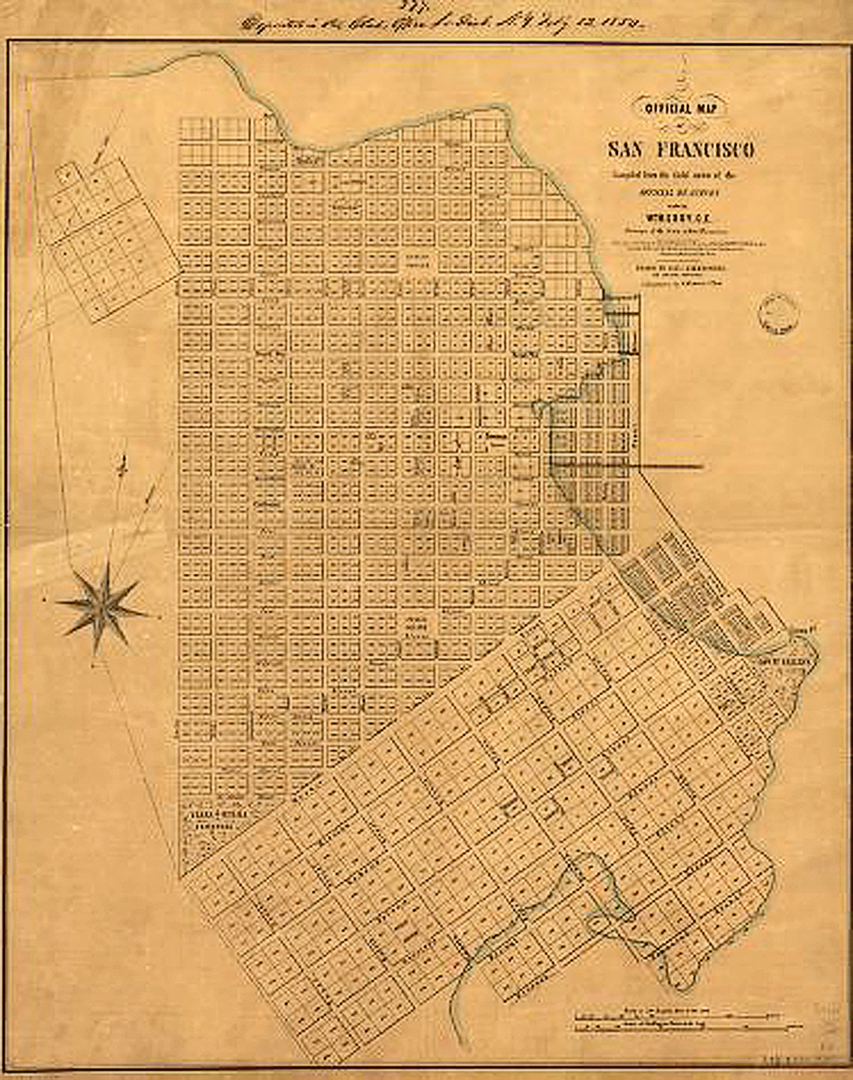

The town’s growth prompted Bartlett’s successor as alcade, Edwin Bryant, to hire an Irishman named Jasper O’Farrell to survey the town and extend its limits. O’Farrell’s 1847 survey projected a grid of streets onto open land covering an area of some 800 acres bounded by the waterfront, Francisco, Post and Leavenworth Streets, thereby setting the stage for further development. Most of the future Uptown Tenderloin was included in William M. Eddy’s 1849 survey that extended O’Farrell’s projections west to Larkin, and the remainder of the district was within the 1858 extension of Eddy’s survey to Divisadero.

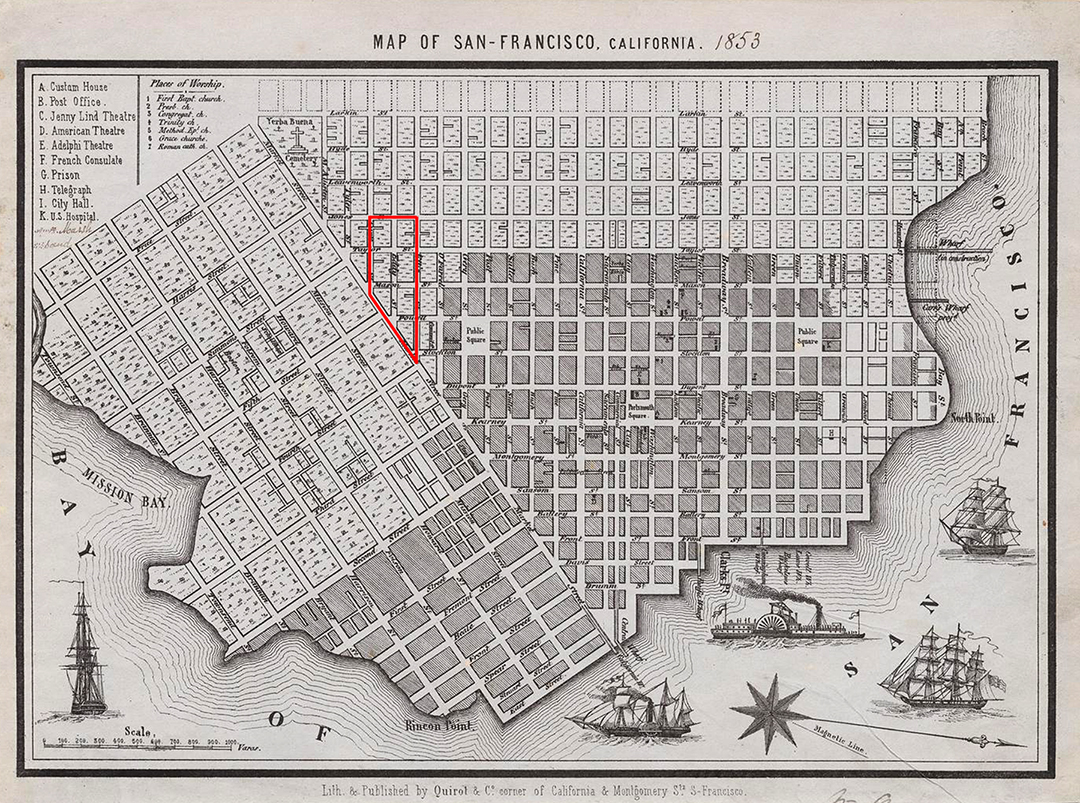

Early development of the district took place in the low area between Turk and Ellis Streets that stretches east from Jones Street to around Fourth and Market, then known as St. Ann’s Valley.

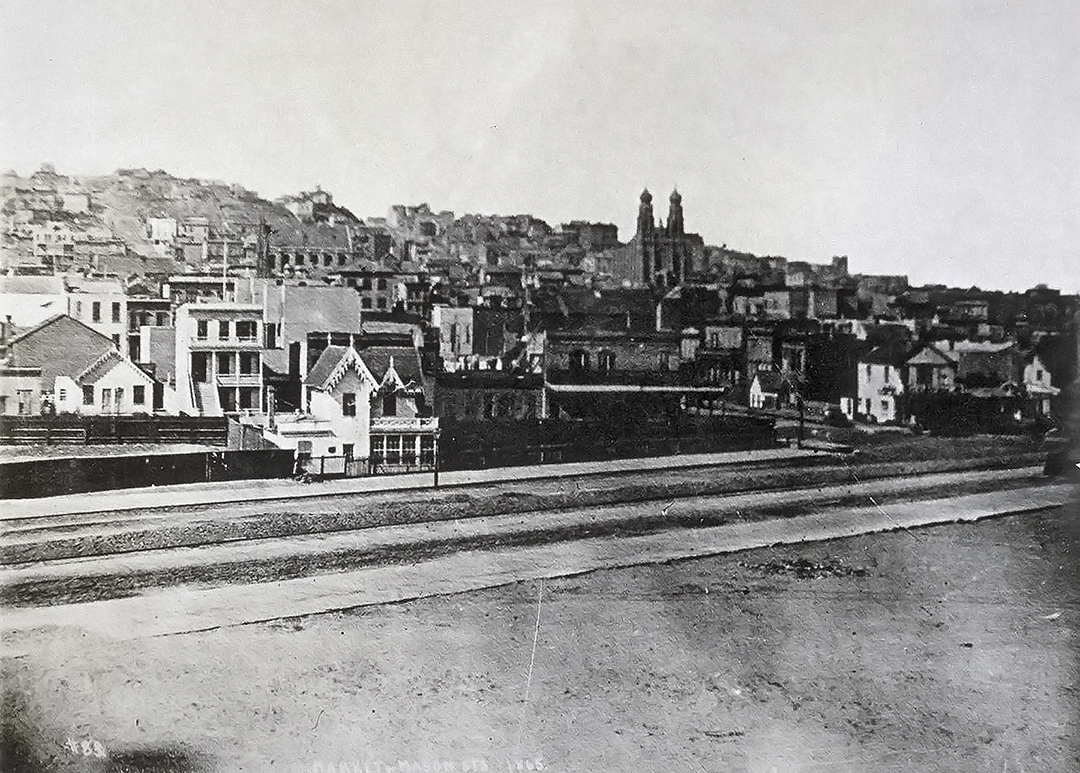

In 1853, there were fewer than twenty buildings in the entire area. Six years later, roughly a quarter of the lots in St. Ann’s Valley and along adjacent streets had buildings on them. By 1865, every street in the district was lined with nearly continuous rows of wood buildings, mostly row houses and flats and some single family houses set back from the street, and the inhabitants were mainly the socially ambitious—the bourgeoisie or middle class.

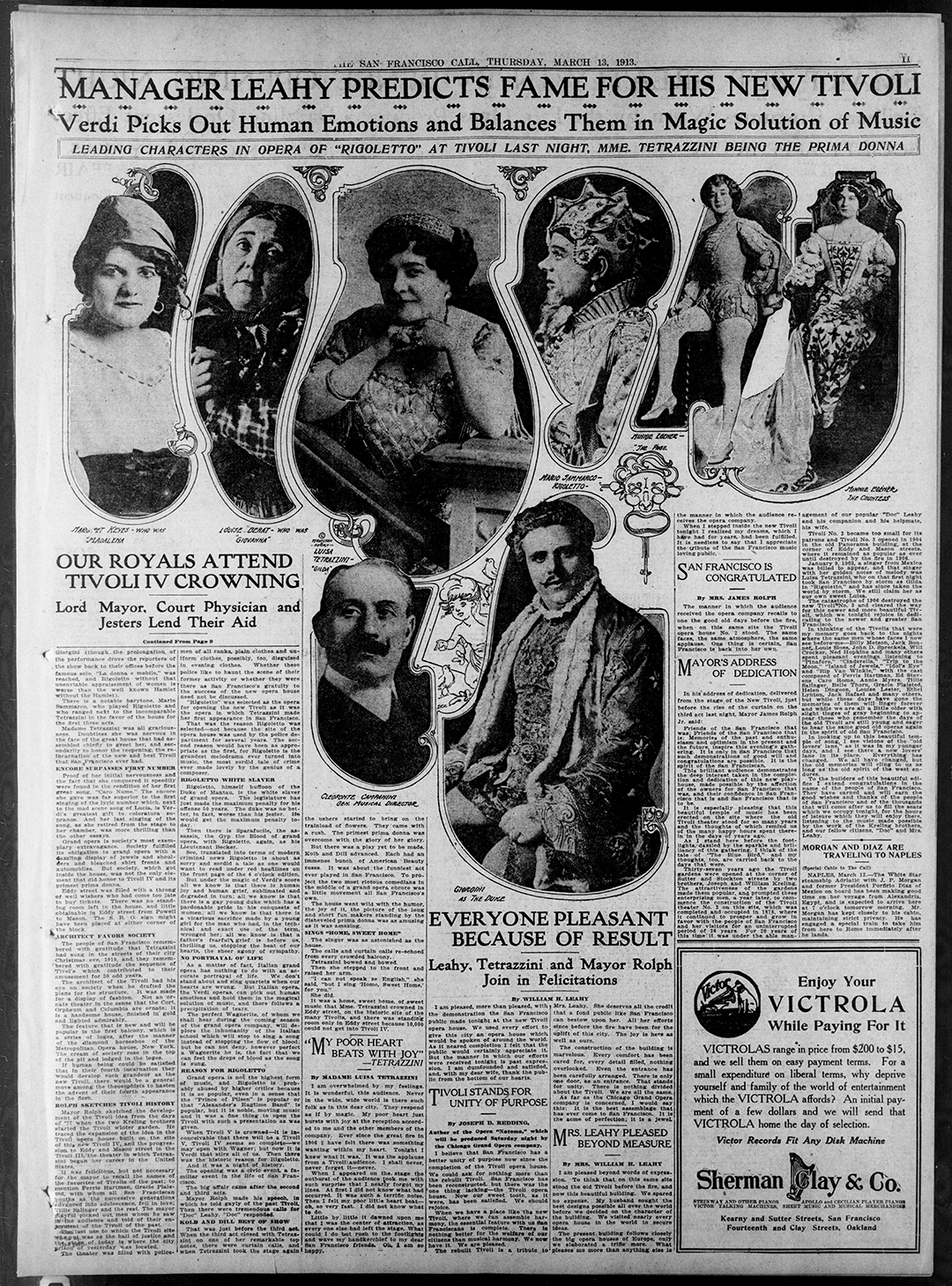

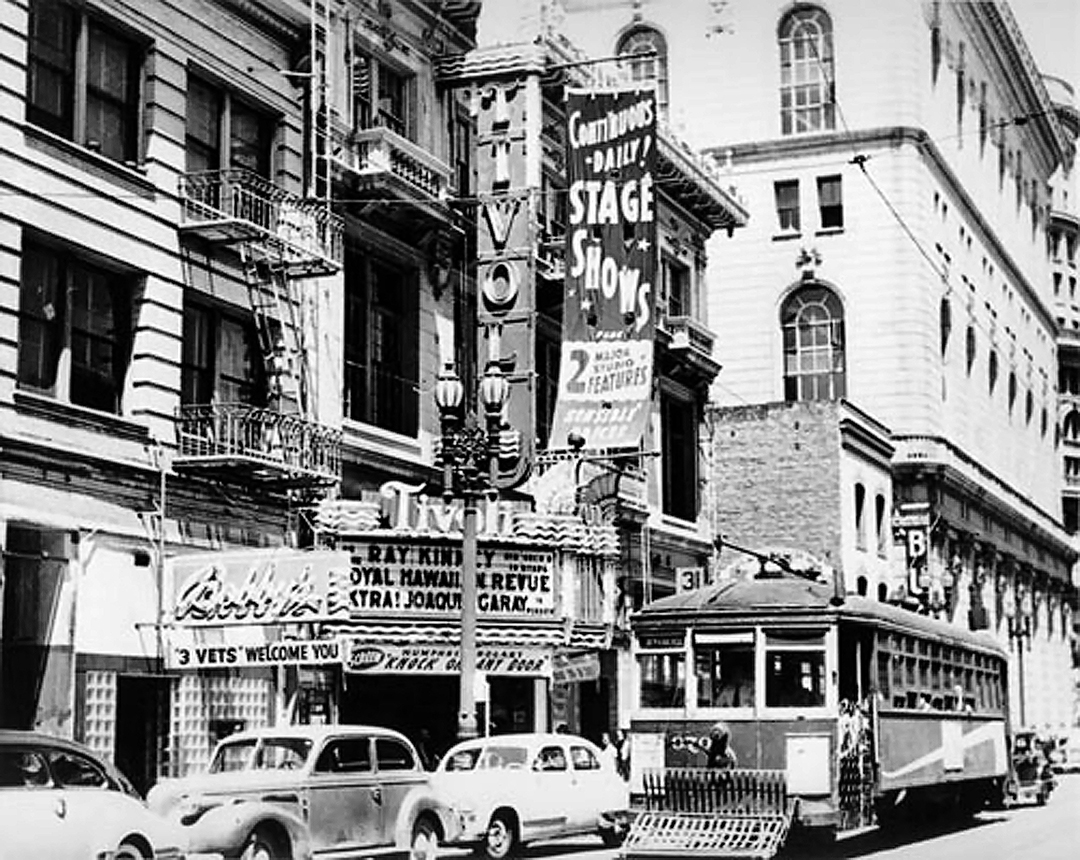

The Tivoli Opera House

In 1877, Joseph Kreling was a young man who thought that San Francisco needed music. Determined to fill that need, he a gave concerts in a former mansion near the foot of Eddy Street by performers that included a ladies’ orchestra from Vienna. When the craze for Gilbert and Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore swept across America, Alice Oates and company performed it in San Francisco, and soon afterward, other comic opera companies appeared on the horizon. Kreling hired various members of these companies, and with them, founded his own opera company in 1879.

A short block from the Tivoli was the newly-opened Baldwin Hotel, full of travelers and businessmen in need of entertainment, and partly through them the Tivoli’s popularity and renown soon became far-flung. For nearly 30 years, the Tivoli Opera House never closed its doors—except in observance of Kreling’s death.

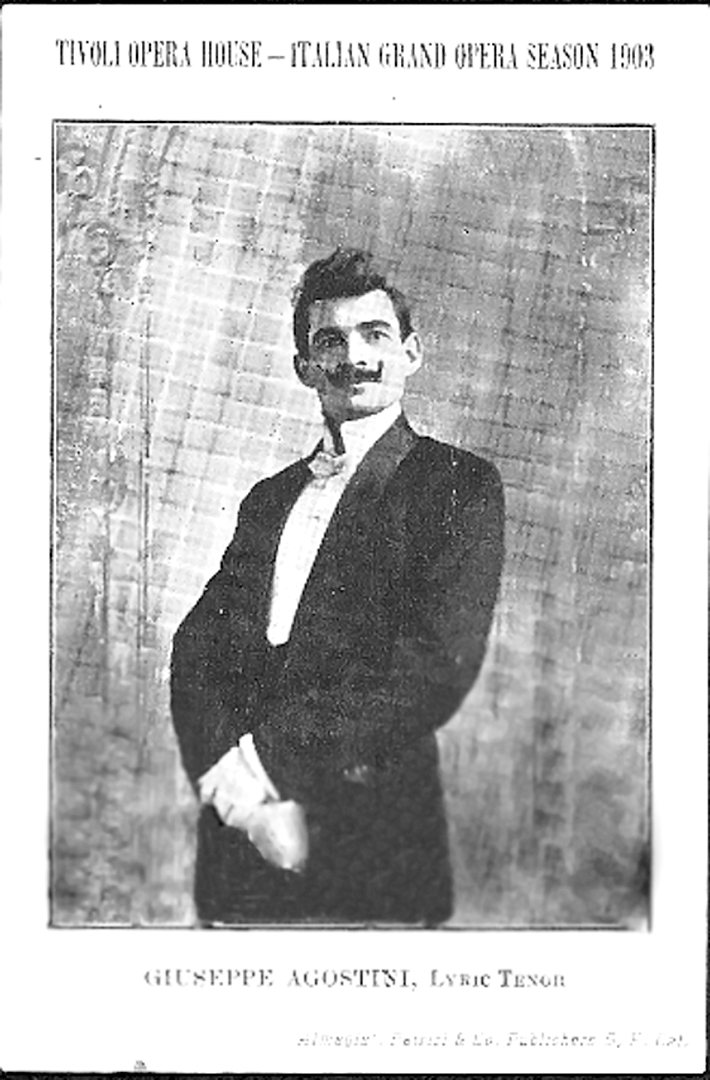

When director W.H. Leahy took charge of the house in 1890, he began producing Italian opera four months of the year with companies he recruited from small opera houses in Italy. In 1903 he built a new Tivoli Opera House around the old Panorama Building on the southwest corner of Mason and Eddy, where the Ambassador Hotel now stands.

While traveling in Mexico late the same year, Leahy heard soprano Luisa Tetrazzini singing with an itinerant Italian opera company in Mexico City. Leahy engaged the entire company, and in 1904 they opened the new opera house in Rigoletto. Singing the part of Gilda despite a cold, Mme. Tetrazzini became an immediate sensation. For the next two years her many performances at the Tivoli packed the house to overflowing, and Luisa Tetrazzini became a star of international repute.

Birth of the Tenderloin

After a Comstock silver lode bonanza made him a multimillionaire, in 1878 Elias J. “Lucky” Baldwin opened a luxury hotel and theater bearing his name on the northeast corner of Powell and Market. In the area nearby were restaurants and saloons where gambling took place, and around 1885 dance halls and parlor houses began to appear in the district. Where the money flows, there also vice goes; and thus from around 1880 through the 1890s, the area roughly encompassed by Market Street, Union Square, City Hall, and Van Ness Avenue—distinctly uptown from the Barbary Coast near the waterfront—developed as a center of entertainment and vice that was subsequently characterized as “tenderloin,” a term that originated in New York.

For more, check out the full entry on Up From The Deep