In June 2014, Sarah Kelaita and her now-husband made the trip from their new home in San Francisco to Chicago for their wedding.

Kelaita’s large extended family descended on Chicago from the corners of the globe. While it was a joyous reunion for family who hadn’t seen each other in years, there was something happening on the other side of the world that would eerily echo an event in Kelaita’s life more than twenty years earlier.

ISIS was in Iraq, advancing on Baghdad. Everyone clustered around the TV at her parents’ home watching the reports. “[It was] just a weird feeling of ‘here we go again’, all of us in front of the TV watching bad things happen to our homeland so many years later.”

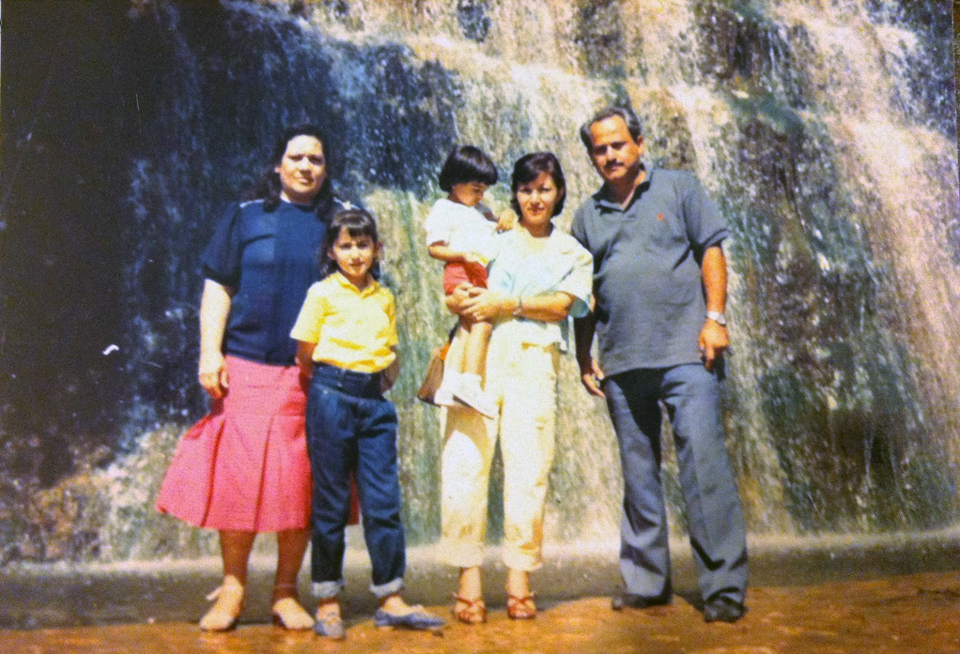

Kelaita was born in Baghdad in 1985. At the time, her father, a conscript in the Iran-Iraq war, was able to return for a short time. “I don’t recall a lot from my early childhood,” she said, “but I do know that … there was this cloud over my mom and the family because they were really worried about my dad’s safety.”

The war was devastating, but her father returned home by the time her younger brother, Yousif, was born in 1989.

Though Kelaita has sparse memories from her early childhood, she distinctly remembers the 1991 event that would create déjà vu for her in 2014: the night the US bombed Baghdad.

“That is actually probably one of my first really clear memories,” she said, “Everyone [was] congregated in the living room watching the news. You could hear the shelling.”

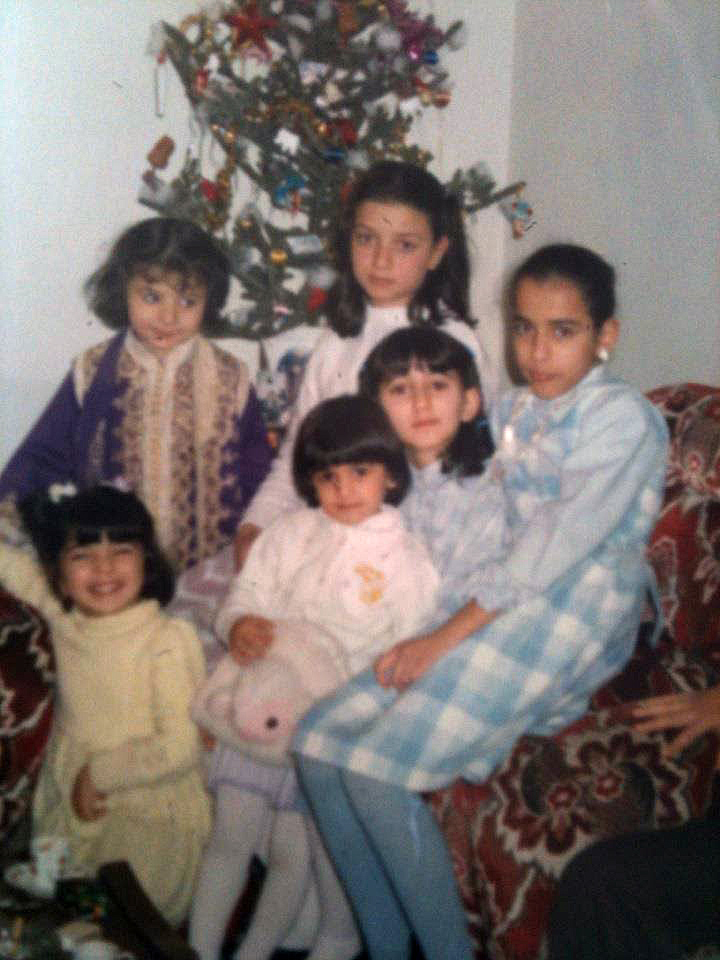

Kelaita says her entire extended family moved to a house in the town of Haweeja to avoid the bombings. For five-year-old Kelaita, nights spent on the floor with her cousins felt “like a massive sleepover.”

The next months would be a blur, with only lingering memories of childlike concerns: having to eat bulgur due to the food shortage, whether the Christmas tree and ornaments would still be standing when they returned home.

Kelaita’s parents had started the visa process for the US in the early 1980s because part of her father’s family already had relocated here. They ended up buying a home and building a life in Baghdad and hadn’t pursued it, but now with yet another war and people they knew going missing, they were concerned again for her father’s safety. They began making arrangements.

Shortly after they returned to Baghdad from Haweeja, the family would leave Iraq for good.

Her family of five loaded into a van with just a few suitcases and drove more than 300 miles to the border with Jordan, leaving behind everything; family, friends and country.

At the time, it was illegal to leave Iraq, so they arrived at the border under the pretense of a vacation to visit family. Kelaita remembers her parents telling the children not to say a word. It took a bribe of all her mother’s gold family jewelry to convince the guards to let them pass.

“It’s almost more difficult for me to think about it now,” she said, “because now I think about putting myself in my mom’s shoes.” She finds it difficult to imagine the choices her parents made for the family’s safety.

“[There are] so many immigrant stories like that,” she said, “where people who have lived this very rich and meaningful life in another place, have to give it up for some reason and start over.”

Just over a year after the bombing of Baghdad, the family arrived in America. Kelaita started school right away and was placed in an ESL class because of her minimal English skills.

Her only previous English was a book she had with her in Jordan. “I had a book that had pictures of a house,” she recalled, “and it would have all the household items [with] the word in Arabic and the word in English and that’s how I was practicing because I knew I was going to move to the US.”

Though part of her dad’s family was in Chicago, they were spread out geographically and she remembers there being less of a family network than they had in Iraq. She said her parents felt the pressures of learning English themselves, finding jobs and putting food on the table. “It felt like those carefree childhood days were over,” she said.

Kelaita learned English quickly and was in a regular class by the next school year. Although culturally there were situations she didn’t understand or small social miscues, like showing up to the first day of school in a taffeta dress while all the American children were in shorts and T-shirts, she adapted quickly to her new life.

Growing up she had to bridge the gap between her American self and her Iraqi parents, explaining things like camping and sleepovers to them.

“They just thought it was really inappropriate,” she explained. They wondered why she would sleep outside when they had a home or why she wanted to sleep at someone else’s home when there was a perfectly good bed in her room.

The transition to America affected each of the siblings in her family differently.

Because her younger brother was just a baby when he arrived, Kelaita said “you could practically say he’s first-generation” American because he doesn’t remember anything from Iraq. Her sister Mary had a much more difficult time.

Ten years older than Kelaita, her sister had to let go of memories and friends, making the event a traumatic one that still affects her.

“I think for me,” she said, “that experience has made me a more resilient person because I notice change doesn’t really bother me. I’m really adaptable.”

Culturally, she said she’s always felt both Iraqi and American. “I feel like for so much of my life I never even thought I was anything but American."

Kelaita felt accepted in Chicago, but when her Google job brought her to San Francisco, she felt a whole other level of acceptance. “It’s a little hard to describe, but it is palpable, the feeling of how tolerant people are,” she said of the Bay Area.

People here don’t always ask about her and her husband’s ethnic differences and she doesn’t always feel the need to provide her whole backstory. She said it’s “sometimes nice not having to be defined by that”.

To find more affordable housing, Kelaita and her husband moved to Oakland. “This is a really cool community, it’s really diverse,” she said. “I would like to bring up a family here.”

Reflecting on the recent immigration bans, Kelaita wondered what it would have been like if she and her family had been refused entry after obtaining a legal visa in 1992. “Where do you even go? You have nothing left where you’re coming from.”

She said she wished more people understood how privileged most immigrants feel coming here, noting that these are people who've purposefully chosen the US as a place to make a new home and raise their families.

“I think that is something people should keep in mind,” she said, “that for a lot of immigrants this is something they’re really been working hard towards and cherish.”