The decision to bulldoze the Western Addition had been made behind closed doors at City Hall, and people across San Francisco in the '60s and '70s were fighting to save their own neighborhoods from freeway and development plans. But they needed to understand how the city worked if they were going to make changes happen.

So a group of recent college grads started covering city commission meetings in early 1972, when nobody else was, and began sending out a newsletter about their findings to concerned citizens.

This is how the Study Center was born. From the political turmoil of that decade through social movements and community organizing efforts ever since, it has found ways to quietly and steadily nurture civic life in San Francisco and beyond.

As a fiscal sponsor, helping nascent nonprofits until they can become independent, it has worked with names you might know today. Here's a sampling:

- WalkSF, a citywide pedestrian advocacy group

- Open Hand, an award-winning meal service for seniors and critically ill patients

- EXIT Theatre, a Tenderloin troupe that puts on the annual SF Fringe Fest

- Friends of the Urban Forest, a leading city tree-care group

As the publisher of Tenderloin-focused newspaper Central City Extra for the last 15 years, it has come back to its early news mission.

It has also had its own struggles. Although it has adapted repeatedly over time, a series of landlords in the central city area have physically squeezed it out to an office space on Mission Street in western SoMa.

We sat down with executive director Geoffrey Link and senior writer and editor Marjorie Beggs to get the full story on the organization’s history and what it's doing today. We've provided links to relevant articles and sites for the curious.

Hoodline: How did the Study Center start?

Geoff Link: We got started in March of 1972, when we got our 501c3 nonprofit certification. We opened up in the Grant building, which used to be a real hotbed of nonprofits – it was really a great building for progressive organizations. [Study Center] was started by recent graduates of the journalism department at Berkeley and community organizers. At the time nobody covered supervisors committees, Planning Commission or Public Utilities Commission meetings on a regular basis. There were only about five neighborhood organizations outside of merchants associations. There was the Mission Coalition, the Coalition for San Francisco Neighborhoods, SPEAK in the Outer Sunset.

The Grant building circa 2010. Photo by Michael Maloney/Time Shutter.

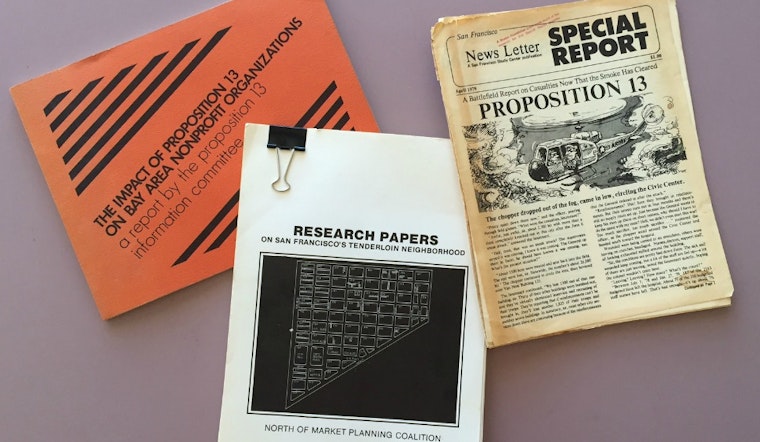

The San Francisco Progress, the Examiner and the Chronicle were not really covering City Hall. We could see that the neighborhood movement was going to be blossoming. So the Study Center was gonna try to help it evolve with the San Francisco News Letter, they called it.

This was two years before I got here. It was an eight-page monthly that covered the supervisors committee meetings, PUC, Planning, Building Inspection. We were trying to be an early-warning system for neighborhood organizers. So we had this newsletter, and we published a book called “Understanding San Francisco’s Budget”, which was like an entryway for neighborhood groups to get involved in City Hall.

Back then City Hall was a mysterious thing, nobody had really been dealing with it. Part of our role was to introduce [neighborhood groups] around at City Hall, to go to the supervisors ... as well as have the news, and the book, about how they could be involved in the budget process.

HL: Explain a little more about what the neighborhood movement was and how it got started. A lot of people probably don't know how San Francisco’s neighborhood focus came to be.

GL: Mission Coalition was probably the most active of the neighborhood organizations, and SPEAK it was called out in the Sunset, Parkside, etc. No one had been organizing for the residents. That’s how it started to grow – the need for residential input into goings-on at City Hall.

Marjorie Beggs: It had to do with what was going on in city planning, with freeways coming through, issues of big-box stores (they weren’t called that then), merchandising, police issues coming to the fore.

People outside of a Mission Coalition meeting in the 1970s, from the Basta Ya! community newspaper, via FoundSF.

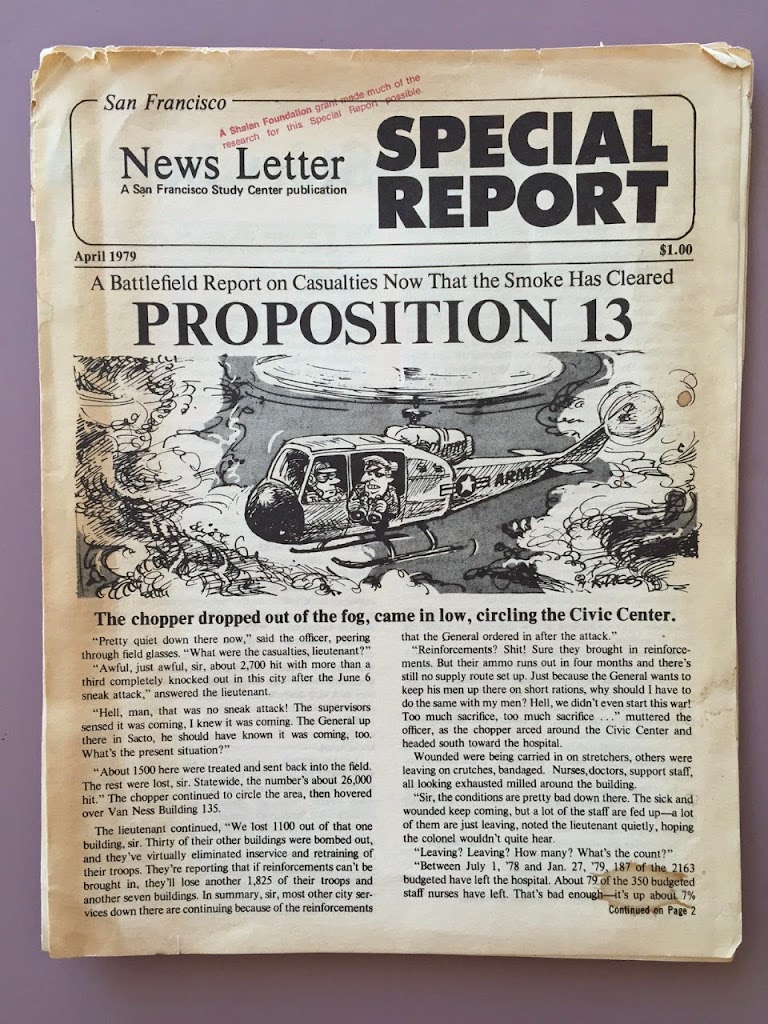

GL: The North of Market Planning Coalition wasn’t going yet in 1972, but in 1978 they got the height limit to level off at 8 stories, which actually preserved the Tenderloin. Zoning was a huge issue because of the Manhattanization of San Francisco. There weren’t really height limits in the financial district and adjacent to that in the Tenderloin.

MB: Redevelopment was tearing down buildings in the Fillmore District, Area 2 – Western Addition. People being displaced. It wasn’t really called “gentrification” then. It was “revitalization” or “urban renewal” but it was actually urban removal. That’s something that continues now, 50 years later. But it really started then. The effort to level whole areas of San Francisco.

A lot of the neighborhoods movement was arts-related. The Neighborhood Arts Program was a very powerful group of people who wanted the city to see art that wasn’t just the symphony, ballet and the orchestra. Grants For The Arts became involved with that, too. There were a lot of complaints about the hotel tax going mostly toward the major arts and not community arts.

That was a very big movement to democratize the arts, and that is still an issue today – although Grants For The Arts has managed to smooth over a lot of that by changing its policies.The arts movement really grew up next to the zoning movement. Then there was Vietnam, and all of the social and political issues. A lot of the people involved in the neighborhood movement were also politically savvy and very active. So that added another whole layer. Then there were hippies. It was a very potent time in terms of people – people potency.

HL: Tell me more about how the Study Center evolved from this period in time.

GL: I was brought in in 74 to be the managing editor of the San Francisco News Letter, because the people who had started the Study Center and were working on the newsletter were recent graduates and didn’t have that much professional experience. I’d been editor of San Francisco Magazine, worked for the Wall Street Journal, freelanced all over the country, I was Billboard’s man in San Francisco so I’d been covering the whole music scene and the growth of that. Working with Rolling Stone as well. So I was told, when I got here, that there were gonna be 10 issues that they had money for, and we’d see whether or not we could make the newsletter grow – because we still had no competition with the mainstream press. Nobody was covering what we were covering. But it turned out there was only enough money for one issue.

Harry Drigg's Study Center logo from the 1970s.

But it seemed like such a great idea that I decided to stick around. We decided to write a proposal to San Francisco Foundation to try to get general support. We got a $35,000 general support grant for three years, and then we were supposed to be out on our own. The thing that was really unfortunate was that the newsletter was too political for the foundation, so they said that none of their money could go into supporting it.

What we did then was become a technical assistance organization. We’d take neighborhood groups around city hall, we’d help people write funding proposals – that was a huge part of our job then.

MB: We had to become a “fee for service” [nonprofit] organization rather than depending on grants from foundations. That means we’d go to other nonprofits – anyone, actually, but most of our clients were nonprofits – and do for them what we’d been doing on our own, which was writing and editing and reporting. We also worked with city offices that were looking for public relations help, and with neighborhood groups.

GL: In 1976 and 1977, the federal government had CETA, the Comprehensive Education and Training Act. And they started spreading money all around the country, kind of like the WPA and [other Depression-era programs] in the 1930s. We got a contract to do a history of San Francisco’s neighborhoods after the Second World War. It was several hundred thousand dollars – way more than we’d ever had. We had 35 staff, mostly reporters but also 7 photographers. And we went out interviewing in every neighborhood we could find. We wound up with 65 neighborhoods. We photographed and interviewed people in their own environment, on their front lawn, in their living room… so we could show who they are. We had fantastic photographers. Lenny Limjoco, who went on to be our designer for decades. He’s the guy you’ll see on the walls in our office. Brilliant photos.

MB: This was an important period of time for the Study Center, because it used the existing expertise that had been built up about neighborhoods, and it gave us some visibility, gave us entrées into other organizations, some of whom became clients.

HL: This was right when the city was going through some big issues, right?

MB: 1978 was the City Hall murders [of Supervisor Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone by former Supervisor Dan White], and that year was also when Prop. 13 was passed. It was also the last year of our newsletter because by that time we had really run out of money to keep it going. I had just come on through the CETA program, but I was really focused on the newsletter. But then we got very busy doing work for other people.

One of the last editions of the San Francisco News Letter, covering the still-controversial Proposition 13.

GL: We helped the North of Market Planning Coalition do the first neighborhood improvement plan “Tenderloin Tomorrow.” It was the vision of what was going to happen in the neighborhood. And that was a fabulous report actually, that was kind of a rarity in the city – where a neighborhood organization was really looking that far ahead. At that time the North of Market Planning Coalition had some really influential people (who are still important today). Richard Livingston was one of the co-directors – he’s the administrative director of EXIT Theatre, which does the San Francisco Fringe Festival, and is among the oldest and most important neighborhood theater groups in the city. And Henry Izumizaki, the other director (who has gone on to run a number of other large nonprofit and charity organizations). And Brad Paul, who is now deputy director at the Association of Bay Area Governments – he’s been involved in housing issues for a long time.

That’s the kinda stuff we were getting into, the longer reports, and helping with research. We would design this stuff and edit it. We did a research project with Skidmore, Owens & Merrill [a large architecture and urban planning firm], which led to maintaining the downzoning of South of Market. I tramped every single block and counted every single piece of property from Market Street to Harrison. We were trying to learn how much industry was there South of Market to decide what the public policy should be. We worked on this report that led to the policy of keeping the height limits low from 5th Street west after we found out western SOMA was all residents and small businesses.

MB: We were doing a lot of research for fees, and creating products and materials and reports for other people. Simultaneously we started working with the Zellerbach Family Fund.

GL: The executive director was Ed Nathan. He was among the most progressive of all the foundation people. For 15 years, the Study Center was the dissemination arm for the Zellerbach Family Fund. We created all of the materials for cutting-edge social services, mental health and self-help projects, things that very few other foundations wanted to touch. Marjorie did what we called the Innovative Services Monograph series. Basically, run down a project’s history, how it operated, trying to give people an idea of how they could create their own versions of these services.

MB: This was a very unusual thing to be doing. There weren’t any other foundations that would fund publications like this. We would write, edit and publish them nationwide.

HL: What are some examples of these programs?

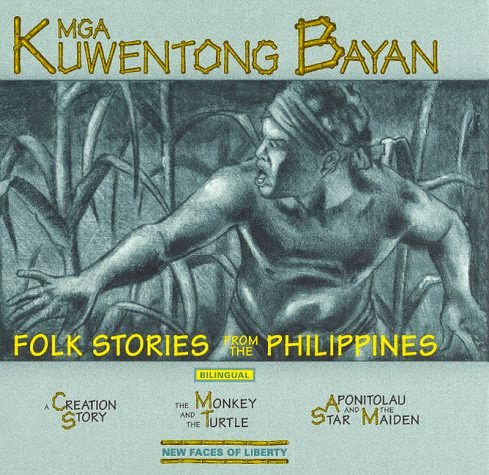

GL: Ed was very concerned about the newest immigrants to the city, primarily from Southeast Asia and Central America. And one of the programs they funded was called New Faces of Liberty – it was a curriculum for grade school students that would help explain the experiences of their classmates. Alice Lucas, one of the educators backed by Zellerbach, took the book 12 Years A Slave, worked with a local music professor, and turned it into audio tapes and period music, as well as a teacher’s guide that included the first slave petition to Congress. Another Zellerbach grantee was Parent Services Project, led by Ethel Siederman, an effort to get parents involved with their kids’ education. It started in four child care programs and has spread nationwide now.

Mga Kuwentong Bayan: Folk Stories From The Philippines, one of the New Faces of Liberty productions.

MB: We helped create, produce and promote materials for around 15 different school curriculum projects. And we did that kind of work until the end of the 1990s.

GL: That’s around when the Goldman Fund, another big foundation, did the first neighborhood improvement grant for the Tenderloin. They awarded a $5 million grant to organize the neighborhood. It was called the Lower Eddy-Leavenworth Task Force because that’s the roughest area of the Tenderloin, and that’s what they were trying to improve. Part of what the neighborhood wanted to do at that time was bring back a neighborhood newspaper, the Tenderloin Times, which had gone out of business in 1994.

MB: It had published for maybe 10 years, and it was trilingual — Cambodian, Vietnamese and English. The idea there was that the Tenderloin was this hotbed of Southeast Asian communities. But it went out of business. There had always been interest in bringing back some kind of newspaper.

GL: I had consulted with the Tenderloin Times in the early 90s, and I’d come to the conclusion that they needed to cross Market Street, because the demographics between north of Market immediately and south of Market was all about the same demographics: immigrant populations, and everybody was poor. The Tenderloin had more disabled and seniors, but everybody had similar values and shared similar needs.

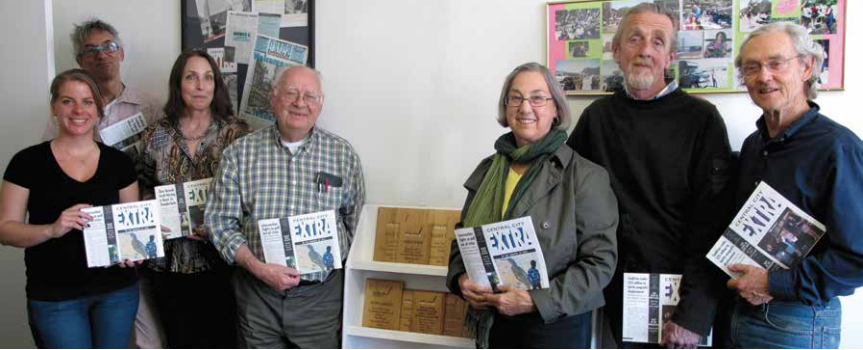

So now we’ve been around about 15 years. Still not making any money, but fortunate to have journalistic and human services roots. Our board of directors is headed by John Burks, the former chair of the journalism department at SF State. Ben Fong-Torres worked with me at SF State when I was the editor of the Daily Golden Gater (a former SFSU publication). Rich Livingston and I worked on Huckleberry’s for Runaways – conscientious objectors [to the Vietnam draft]. Reiko Homma True was the former director of community mental health services. Tina Tong Yee was the head of client relations at Community Behavioral Health Services. We have this nice mix of professional journalists and experts in human services.

The first edition of Central City Extra.

Really we’ve got a board that supports our roots, and so the fact that we lose money on this, they see what we do –“News as a community service.” That’s how we’ve approached this, and that’s why we’re still publishing even though we’ve never made any money. Clear-minded journalism serves the common good.

HL: Tell me more about your favorite stories from the last 15 years.

GL: I think really, overall, what we’ve tried to do with the Tenderloin is to look at issues that are mundane but significant, and try to take a tack in the reporting that looks to the levers that get pulled to move things in one direction or another. We take a narrative approach to our stories, to tell them in magazine-like ways. There aren’t many single-source stories. We don’t try to be objective — we try to be fair. We try to look for the angles that not everybody knows about. I think one of our best pieces, “The Live-In Thief,” was about someone who lived in the Grant office building for five months and ripped everybody off. We’ve used poetry to do reporting through Ed Bowers, who we consider to be the neighborhood’s leading poet. The Twitter tax break. We are the only source of information about the tax break and how it affects the neighborhood. There have been a few stories in the Chronicle that are told from the point of view of City Hall. So yeah… it makes it seem like it’s all smoothness and light. But what we’re looking at is public money. These guys signed on to mitigate the gentrification of the neighborhood. Since this is public money, we have the right to know what’s happening. They’ve talked to us on occasion, but Zendesk is really the only one that will respond to us. The city administrator that runs that whole tax break program – we can’t get anything out of them. If they don’t think you’re trying to help them, they’re not very interested in discussing it. And all we’re doing is asking questions.

We were covering the South of Market stabilization fund – where the guy just absconded with $1.3 million. We reported, not that, because it hadn’t happened. But we were the only ones reporting on the stabilization fund – on what the money was supposed to be used for.

Chris Daly put the arm on these developers but didn’t put any enforcement into the legislation. On paper they had to pony up, but they didn’t really have to. Because he was too busy being progressive or something. So we started writing about the stabilization fund that was supposed to be helping the neighborhood. Another issue: We were the first to say that the city had an 800,000 population – when the AP and the Chronicle were calling the population 735,000. five or six years ago. Because what we did, we went to the state and saw how they count the population.

MB: It sounds like a modest achievement to get the number right, but it has real ramifications financially for federal money, state money. Depends on how much you’re gonna get for which population. In a poor community it’s really significant.

The Live-In Thief issue cover.

GL: Another issue is the community benefits district – something you don’t see covered much. Central Market CBD, the North of Market CBD. There’ve been a lot of things that have not been necessarily picked up by other press.

MB: One reason is that they are complicated stories that take time to develop. When you’re doing a daily newspaper it’s a different kind of news. That’s okay too, but they just don’t have the time and expertise in some cases to dig into those stories.

One other thing about the Study Center’s changes is that they were concurrent with changes in publishing. Nonprofits started doing their own writing, editing and design, and a lot don’t have the money to pay professionals. We still do some work with foundations, but our clients of the past just aren’t there any more. That’s too bad.

HL: Tell me more about what you’re doing now besides CCE?

GL: Fiscal sponsorship is what keeps us going. It’s become our lifeblood. Our first fiscal sponsorship project was the neighborhood bicentennial committee back in 1975. They got $150,000 and they came to us. We do the fiscalsponsordirectory.org, as a resource for the field. We edit and publish Greg Colvin’s “Fiscal Sponsorship: Six Ways To Do It Right,” which is the book that transformed the field from the concept of fiscal agents to fiscal sponsors. To show that the IRS, what they wanted to see – the relationship between the donor and the sponsor in charge of the money. It’s a sponsor, not an agent who is in charge of the project.

MB: Our sponsorship ranges from very tiny projects, like with a budget of $2,000, from which we take $200 to serve as its sponsor, up to projects with a million-dollar budget.

GL: We take 10%, but we’ll also take on a project that doesn’t have any money yet, because we think it’s a good idea. We’ll take it on because we think it’ll help the community.

MB: Some of our early projects are still around. EXIT Theater, Friends of the Urban Forest, Open Hand. I think the founder of Open Hand was cooking meals for the AIDS patients out of her kitchen at the time.

GL: Walk San Francisco, like six or seven years back, just a short time. They got their 501c3 pretty quickly.

The Central City Extra staff in November, with Geoff and Marjorie in the center. Photo by Leonor Vera/CCE.

HL: What is the book Death In The Tenderloin really about? Presumably more than just what the title says.

GL: That’s the book we’re proudest of. Even though the title sounds like a murder mystery, it is actually about life in the Tenderloin. The 99 obituaries, that we edited from more than 220 into this book – if you read that book and you read those stories, you get a feel for the nature of the people who are the residents here. We interspersed it with features that we had published in the Extra, that talk about aspects of life and death. We did something on murder, that was one. The main causes of death in the neighborhood. What we were trying to do was give a picture of the neighborhood through recollections, plus reporting. A lot of the obituaries are pretty well reported, like Hank Wilson, the “Teresa of the Tenderloin.”

MB: One of the reasons we even thought about compiling them into a book was that over and over again people told us they loved the obituaries and always read them. We’d get calls or comments from people when we happened to not have any in an issue.

GL: It recognizes people in print who never would have been recognized otherwise. We’re pretty realistic about it. Whatever people say, we’re willing to report, even if it doesn’t make them look like saints, like what maybe you’re supposed to do with obituaries. It’s a book that we think really reflects the Tenderloin. It really hasn’t gone very far because it got few reviews. But that doesn’t diminish its value.

You can read Central City Extra in print every month when the latest edition gets distributed around the Tenderloin area. You can also read it in PDF form online, including a rich set of archives. You can also purchase Death in the Tenderloin on Amazon.