Last month, we asked readers to nominate local people, businesses and organizations that are doing good in their communities to be featured here on Hoodline. This week, we're running a series based entirely on those reader suggestions. Here's one such story.

In October of 1999, Jeremiah Jeffries stood on the median strip of Van Ness Avenue, in front of City Hall, with a dozen other teachers. Each of them held signs scrawled with messages like, “Got pencils? We don’t.” “Got paper? We don’t.” “Got computers? We don’t.” Around them, drivers were honking their horns in support. Occasionally, one would lower their window, and a teacher would weave through traffic to collect the pencil or piece of paper they were offering, before quickly scurrying back.

News of it went national. In the midst of San Francisco’s first tech boom, when money was suddenly pouring into the city, teachers were panhandling for school supplies. Each year, teachers were spending hundreds of dollars of their own money for basic items in their classroom. In response, Jeffries, along with Mark Sanchez and other educators of Teachers 4 Change, an activist group that they founded a year prior, went to the streets. “As a result,” Jeffries recalled, “the district decided to increase the school supply budget for the first time in decades.”

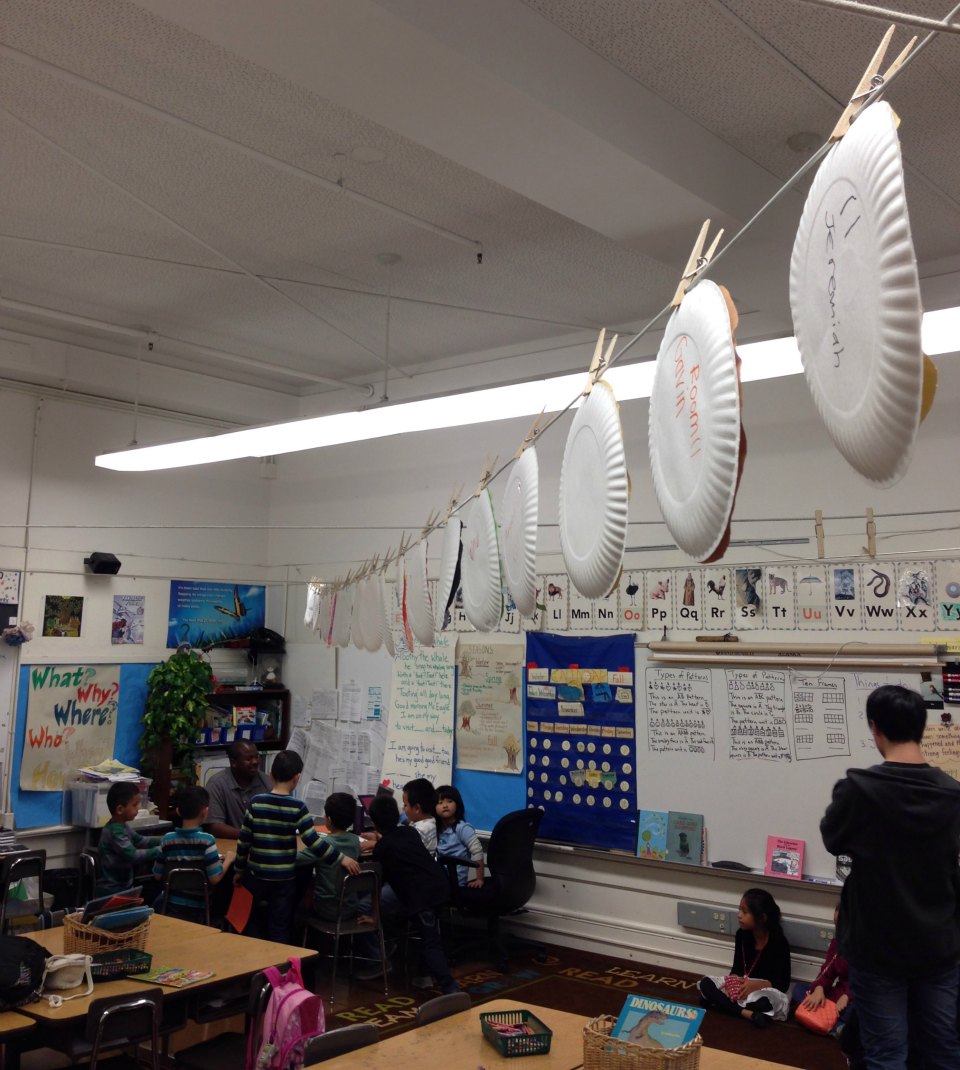

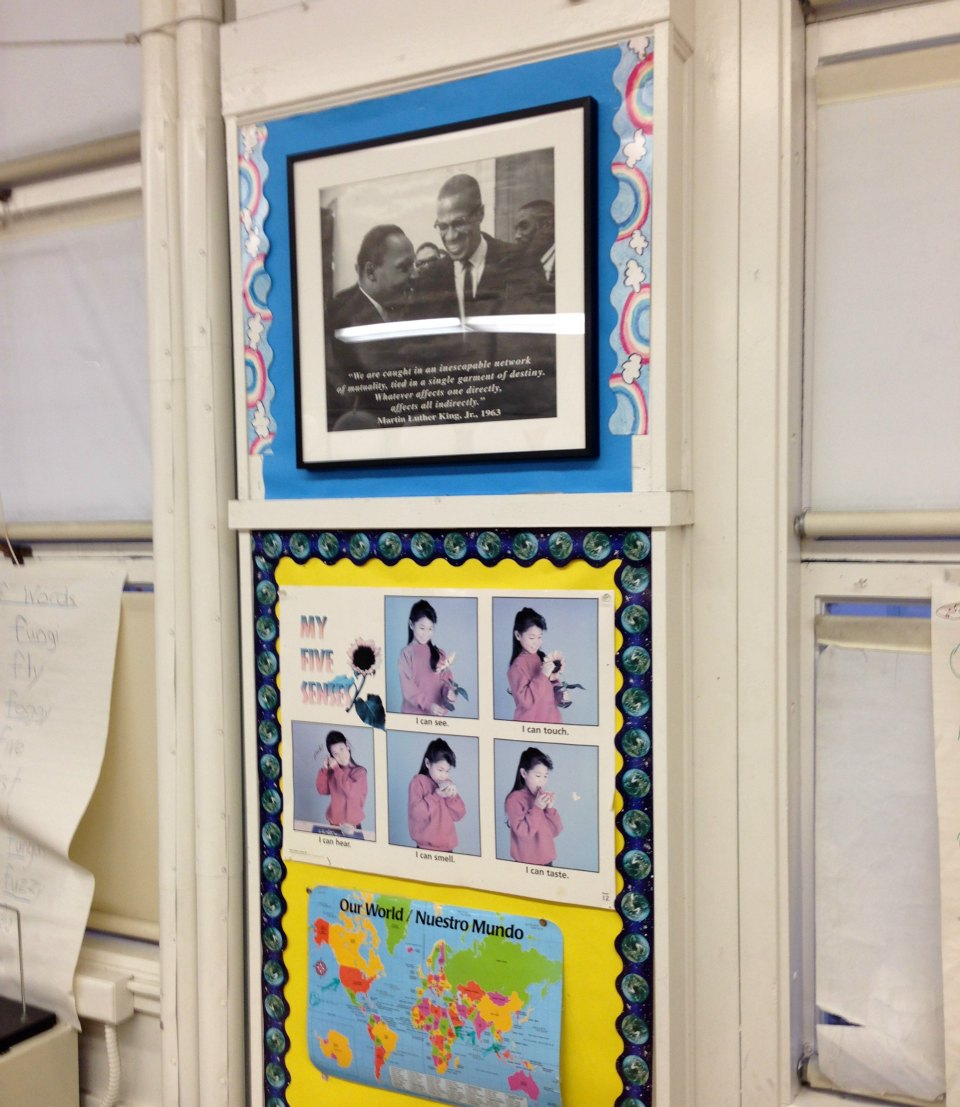

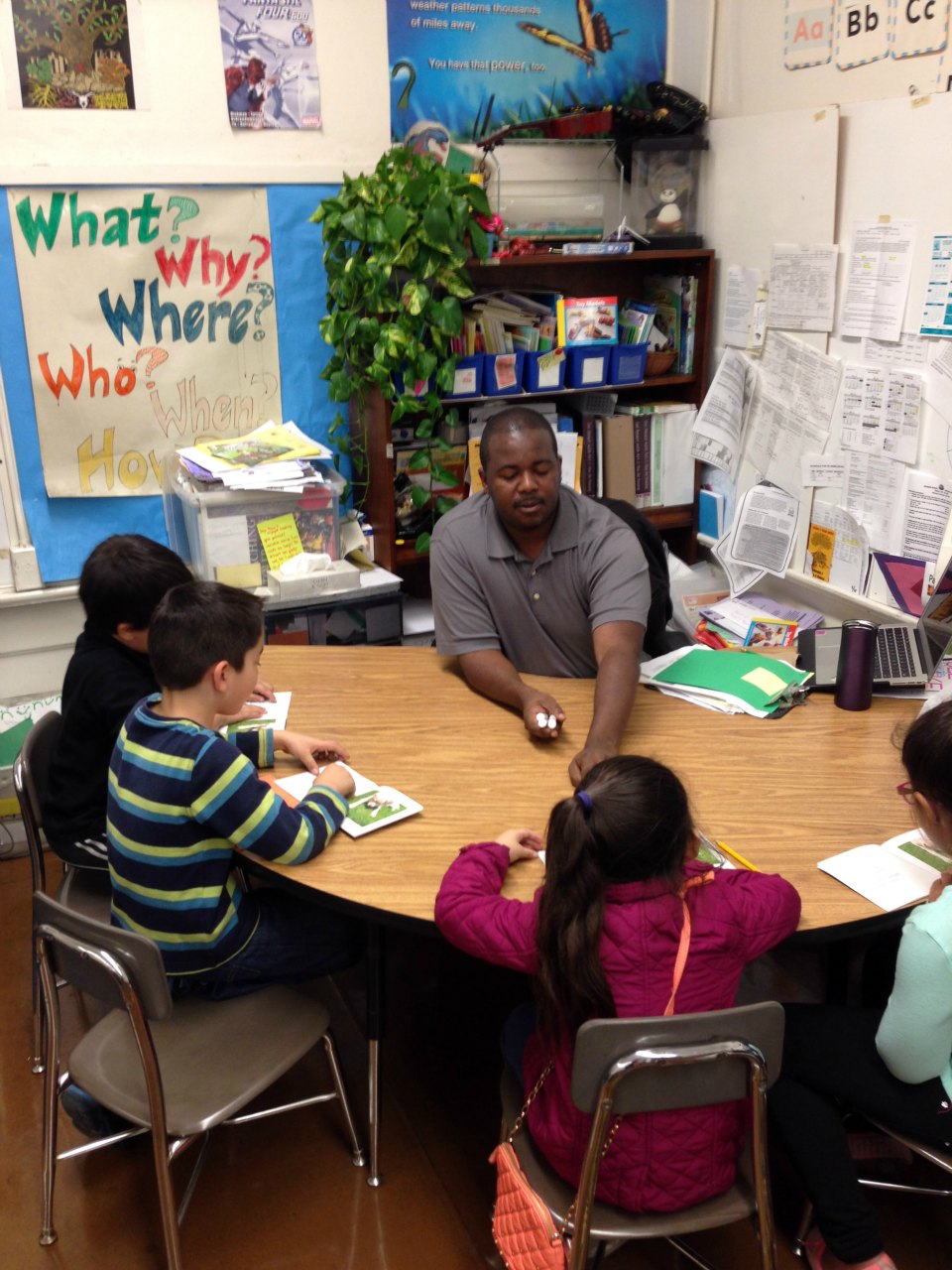

Jeffries is a short, soft-spoken man with an easy smile that often hides his intensity. He has been teaching first grade for 16 years now, and is currently at Redding Elementary School at Pine & Larkin. In many ways, he seems like a typical educator. His classroom is bright and cheerful, decorated with books and art projects and carefully spelled-out words. On one wall, a framed picture of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X is hung above an inspirational quote.

At the time of the protest, however, he had only been in San Francisco for three years, and had barely been teaching for one, but had already begun to assert himself into the conversations surrounding San Francisco education policy. Since then, he has helped push for systemic change on the school board, become an advocate for multilingual and multicultural curriculums, crafted vital education policy, and fought against the ongoing privatization of schools. By way of all this, he has sat on the board of the SFUSD teachers’ union, the Center for Critical Environmental Global Literacy (CCEGL), and co-founded Teachers 4 Social Justice, another advocacy group.

Perhaps most significantly, however, at least four school board members, past and current, have relied on his influence to get elected, while many more hopeful candidates have regularly sought out his endorsement. And, although he has been asked numerous times and would likely find a host of willing supporters, he refuses to run for a seat himself. He prefers his place in the classroom, behind the scenes. As such, he may be the most important teacher in San Francisco that you don’t know.

Jeffries was born in Germantown, Philadelphia, in the mid-'70s, to a large family—he was the seventh of 10 children. He describes his family as poor and Philadelphia as a rough place to grow up. Crack was reaching epidemic portions and, with it, violence and institutional racism were eroding the city. Despite this, his parents, who were prominent in the Nation of Islam and had established the Sister Clara Mohammed School, emphasized the value of community-building and service. “There’s nothing mysterious about progression,” Jeffries remembered his mother saying. “It’s working instead of wishing.”

This lesson became especially important when Jeffries’ oldest sister was shot and killed. The tragedy refocused his family and forced them into new roles. Everyone suddenly had to take on more responsibility and, aged 12, Jeffries began work as a janitor at a child-care center. Later, he credited this job as inspiring his initial interest in education. (“I’d love to be a teacher here,” he remembered thinking.) He kept working throughout his youth, often through Philadelphia’s Fill a Job program, an experience he says kept him out of trouble.

Eventually, he went to the University of Virginia, where he encountered an even more turbulent form of racism, embedded not only within fellow students, but within the faculty and staff. “The culture there was bad to even talk about,” he said. “You could never get your needs met. And, when it was talked about, it was your fault for bringing it up.”

Regardless, Jeffries applied the principles his parents had taught him, and began working for change. With the Black Student Alliance, he exposed how the university was using janitorial staff to increase their diversity numbers. They got the first black female voted into student office. They challenged the honor system, which unfairly penalized students of color, and established a multicultural “Mosaic House.” Still, after graduating, Jeffries was eager to escape the South. Looking for someplace with no winter and good public transportation, he moved to San Francisco.

Mark Sanchez is integral to Jeffries’ success. A fellow activist and elementary teacher, Sanchez was central to the founding of Teachers 4 Change and, later, Teachers 4 Social Justice. In 2000, shortly after the panhandling protest, Sanchez, with Jeffries’ and his organization’s backing, decided to run for a seat on the Board of Education. Jeffries counts his win as a defining moment: “It dramatically shifted everything,” he said. “We could actually start make significant changes to schools in meaningful ways.”

Their antagonists were board members like Dr. Dan Kelly and Jill Wynns, who has been serving continuously on the board since 1992, despite having no experience as an educator. “Most of the people on the school board aren’t actually that knowledgeable of schools,” Jeffries described, exasperated. “They haven’t taught at all. All their information comes from the high-salaried people in the district. Because of this, their decisions end up being very one-sided towards that group.”

Jeffries began focusing on filling up the board with more teachers and educators. In 2002, he helped Sarah Lipson, another teacher, get elected. Then, in 2006, Jane Kim, a youth and community organizer, was elected. In 2008, then again in 2012, Sandra Lee Fewer, the former Director of Parent Organizing and Education Policy at Coleman Advocates, became a board member, too. The three of them, along with Eric Mar (also elected in 2000), helped push the progressive policies of Sanchez and Jeffries.

However, all of them found themselves continuously clashing not only with the elements of Dan Kelly and Jill Wynns, but with the contentious leadership of SFUSD superintendent Arlene Ackerman. Hired in mid-2000 to replace the scandal-plagued tenure of Waldemar “Bill” Rojas (whose exploits eventually brought in the FBI), Ackerman was a polarizing figure for many. Lauded in some circles for reining in spending and increasing test scores, she drew heavy criticism for closing down schools, decreasing student enrollment, and increasing privatization.

In 2006, responding to Ackerman’s closure of John Swett Elementary, Jeffries organized what he still believes to be San Francisco’s largest school boycott. “Over 200 families did not bring their children to school,” Jeffries said. “Instead, we went across the street to the school board and rallied and protested and turned it into a day-long civics lesson for the kids.”

Despite these efforts, the school board voted 4-3 to close John Swett. Soon after, however, Sanchez and the progressives on the board were able to force Ackerman’s resignation, but not before the other board members voted to give her a $300,000 severance package. Jefferies sued Ackerman over this, claiming this was public money, but since the decision was made by board members in a public forum, the courts sided against him.

Ackerman went on to become the superintendent of Philadelphia, where she was let go in 2011, but with a much meatier $905,000 severance package this time. To widespread outrage, she applied for unemployment compensation shortly after that.

These sorts of fights can take their toll. Before the school boycott and the Ackerman battle had even gotten off the ground, Jeffries was already repositioning much of his energy and capacity toward an organization that he and Sanchez had spun out of Teachers 4 Change.

Teachers 4 Social Justice (T4SJ) was formed in order to “help teachers build their practice and become better teachers,” in Jeffries words. Unlike its predecessor, which focused more on union accountability, T4SJ is centered less around local political activism and more on larger policy work. This includes giving teachers the tools to attack thorny cultural topics (race, class, etc.) while creating a curriculum that engages students and families with their communities. To this end, they hold an annual conference (completely free, including lunches) that regularly attracts 1,500 or so attendees, and that has dozens of workshops with titles like “#Tweet4Change: Students Challenge Status Quo via Social Media.” In addition, they organize a series of smaller “social justice salons,” in which people (teachers, students, parents, anyone) are encouraged to talk openly about issues surrounding education. Most recently, they discussed Black Lives Matter and put together a library guide.

T4SJ’s efforts have garnered the attention of likeminded groups across the country, and led to the formation of the catch-all Teacher Activist Groups, or TAG. Its members include the Association of Radical Educators in Los Angeles, the New York Collective of Radical Educators in New York, and the Metro Atlantans for Public Schools, among many others. Their most prominent work, by far, has been the “No History is Illegal” campaign, a national response to Arizona House Bill 2281, which banned Mexican-American studies. Due to their efforts, the curriculum is now taught across the U.S.

Jeffries is also the acting president of the board for the Center for Critical Environmental Global Literacy (CCEGL). Formed from an international Master’s program at his shuttered alma mater, New College, the CCEGL is a nonprofit that sends 10 teachers twice a year to communities in El Salvador and Oaxaca to teach students and other educators about the impacts of globalization and promote indigenous culture reclamation.

In addition, Jeffries teaches education postgrads at the University of San Francisco, as well as first graders, five times a week, in Lower Nob Hill.

Teaching can be a difficult profession, Jeffries admits. “You have to be good to yourself,” he said. “You have to eat. You have to sleep well. You have to be patient, both with yourself and with your students and their families. You have to know when it’s not meant for you.”

This sort of blunt, rational assessment is in line with much of Jeffries’ work. Talking with him, it’s very clear he loves teaching — words like “joy” and “inspiring” are peppered throughout his conversation — yet he is still pragmatic about what needs to be done.

For instance, he remains concerned about finding more competent and experienced educators to put on the board. (Currently, only one, Sandra Lee Fewer, has had any professional experience as an educator.) San Francisco and its schools, he believes, exists in a bubble, one that is anchored by the authority of a democratically-elected school board, which in itself draws its legitimacy from its members’ priorities. Were too many of them to begin listening to the needs of administrators, or even corporations, instead of the students themselves, the closures and charters sweeping across other cities could easily come here.

“San Francisco has been very lucky, in that we’ve been able to fight off a lot of privatization efforts because we’ve had a locally-elected school board,” he said. “When there was talk of Leland Yee, Gavin Newsom, and they began to even speak of mayoral control, we jumped right on it and shut it down.”

“However,” Jeffries warned, “the spectre of privatization and trying to take local control away is always around the corner. Right now, all across the country, people who know very little about what it takes to educate a child are making decisions about schools. They are making huge decisions—huge decisions—that will have decades of effect.”

He smiled, then said, “I still have a lot of work to do.”

Thanks to Bradley R. for nominating Jeremiah.