After World War II, American cities were transfixed by a bold social experiment that came to be known as urban renewal.

Proponents, including leading liberals as well as business and civic interests across the country, believed razing and replacing large swaths of economically depressed older neighborhoods with bigger new buildings would result in lower crime, economic growth and a higher standard of living.

San Francisco became a key testing ground for the concept from the 1940s into the 70s, with large portions of the Western Addition around Fillmore Street getting bulldozed and eventually rebuilt.

But the promised benefits didn't materialize.

The backlash to these failures dovetailed with the growing anti-freeway movement of the same period, the nationwide civil rights and anti-war movements and dozens of other groups to create San Francisco's modern progressive political identity.

To this day, the destruction of the Fillmore is used as a main argument against large-scale planning proposals of all types. For example, a new generation of city planners has proposed rezoning many San Francisco neighborhoods for more density if each new building designates a significant portion of its units as affordable housing. Local activists who are opposed to the plan argue that it's "the Redevelopment model... and that model didn't work."

In this first article, we'll look at how 20th-century housing policies, World War II, and a very different era of urban history led to a mire of problems in the 60s. Next week, we'll look at the aftermath and what can be learned.

Post-War Redevelopment Kicks Off In California

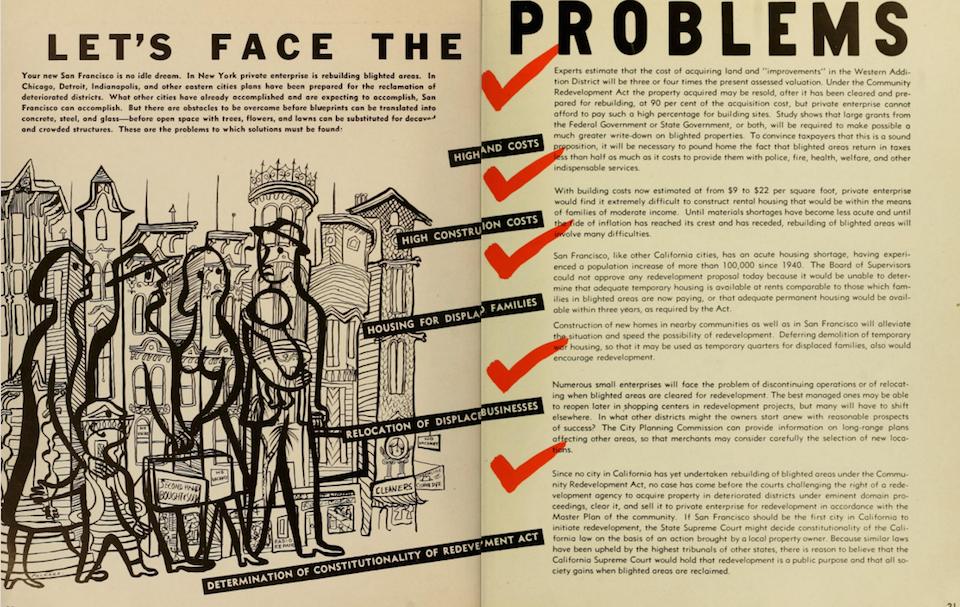

Razing slums was key to reviving city centers, held the prevailing wisdom for many decades last century. In his 1949 State of the Union, President Harry Truman hailed "slum clearance" as a weapon to combat the nation's post-World War II housing shortage. As a 1945 San Francisco Chronicle op-ed stated, "bluntly, nothing can be done to improve housing conditions here until a lot of people clear out."

The California Community Redevelopment Act of 1945 created a framework for funding and implementing urban renewal on a local level. After World War II, California's economy was running hot, but the state had a severe housing shortage and its cities maintained large pockets of depressed areas. In a postwar environment of optimism and well-connected developers, codifying urban renewal looked like a strong play.

The CCRA (and a subsequent 1951 update) allowed municipalities to create redevelopment agencies (RDAs) that could issue bonds against expected earnings and property tax increases and sell mortgages to finance massive undertakings that literally leveled entire neighborhoods. Conceived as public, for-profit corporations, redevelopment agencies were vested with significant political and regulatory abilities.

Innovative for their time, these laws created a system where state and federal funds combined with private capital to fund large-scale redevelopment in city centers. Local planning commissions were tasked with identifying areas that would be declared as blighted and redeveloped.

If officials approved, RDAs would then spring into action with a master plan for housing, density, commerce, traffic management and zoning inside the blight zone. Agencies would purchase, condemn or use eminent domain to aggregate large parcels of land using some state and federal funds, along with private investment.

As a legislative columnist for the Chronicle noted, "the bill is not a public housing measure and is not intended for one."

Any gains in property taxes within redevelopment zones were reinvested in RDAs and used to pay off their debts; by the 2010s, 400 agencies were receiving about 12% of the state's property taxes.

When proposed, the CCRA drew widespread support from planning advocacy groups, general contractors and real estate associations; after its passage, about three-fourths of cities across California eventually established redevelopment agencies.

Urban Renewal Comes To The City

Western Addition residents were alarmed by the state plan and its possible implications for them, but did not present an organized effort to block it.

Several homebuilders and unions were opposed (although trade groups reversed their stance in later years as their members benefited from the construction jobs provided by growth).

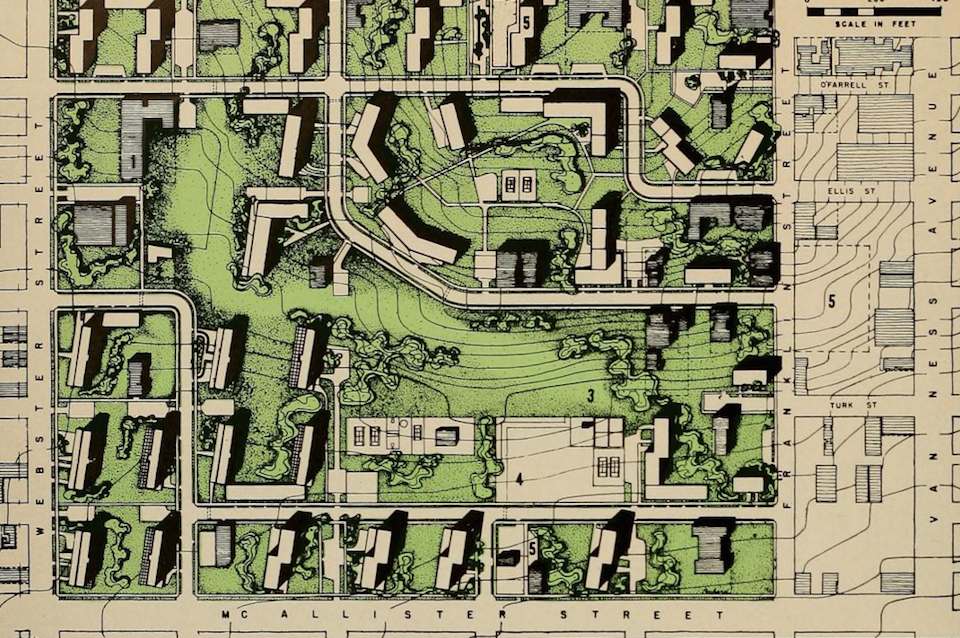

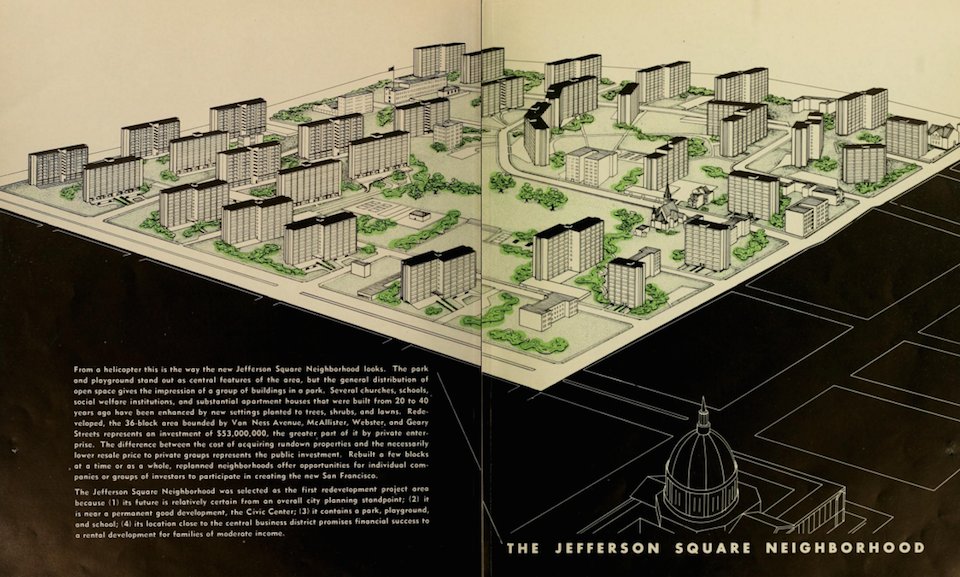

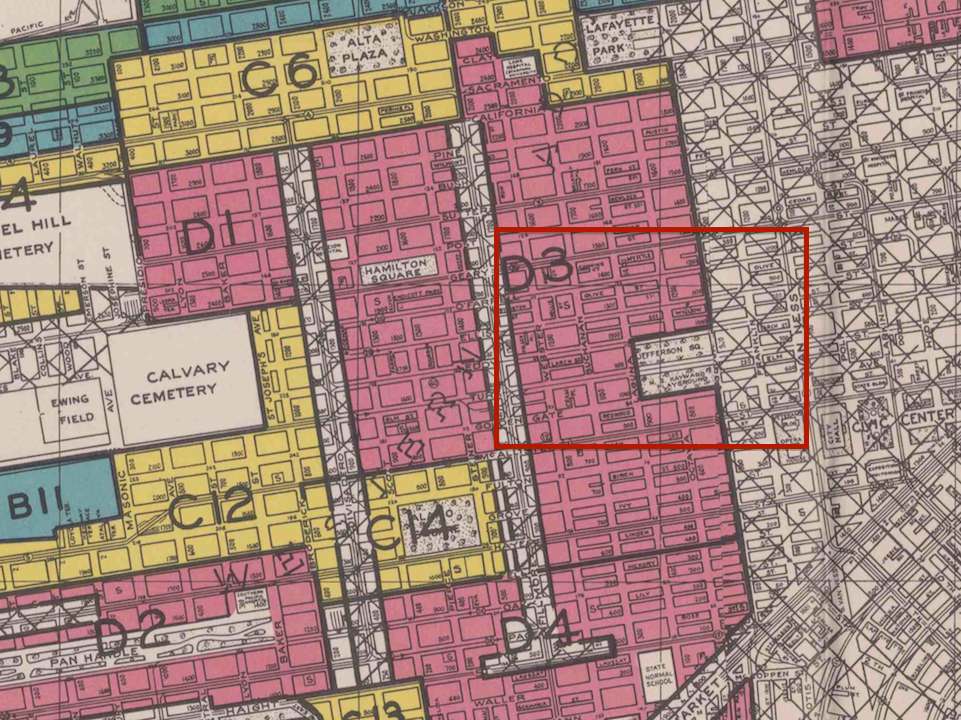

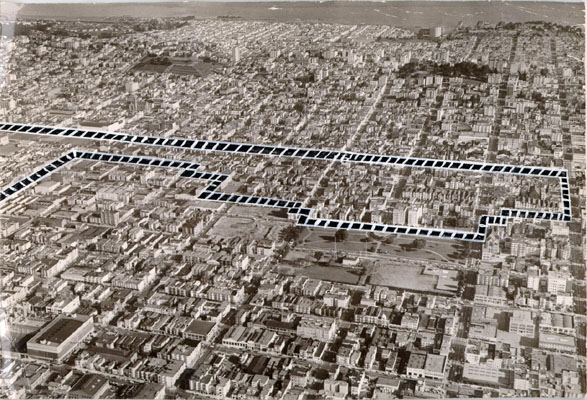

On December 4, 1947, San Francisco's City Planning Commission submitted a $52 million proposal for razing and rebuilding a 36-block zone in the Western Addition enclosed by by Van Ness, Webster, McAllister and Geary (then a two-lane street). A summary titled "New City: San Francisco Redeveloped" called for 33 new 10-story buildings across nearly 2.25 square miles, including larger school and recreation facilities, a shopping center and housing for 10,000 people.

Planners estimated that new housing units would rent for $25 to $30 per room per month — even though San Francisco's median gross rent was already pegged at $32 per month in the 1940 census.

"It is true that a number of people there could afford to pay the rents that will be required," said City Planning Director T. J Kent, Jr. at the time. "But the rents will be too high for a large group of residents."

He added that there was "no pat answer" for accommodating people who were to be displaced.

Supervisor Chester MacPhee, who was generally opposed to public housing, promoted relocating residents to temporary postwar housing, pressuring the federal government for additional subsidies and lowering the required return on redevelopment funds from 90% to 60%. Ultimately, Phee said San Franciscans "will save money through a reduced cost of providing city services to the area."

Those opposed to redevelopment had little recourse in a pre-Civil Rights era; the neighborhood had scant political clout, and most residents were tenants, not homeowners.

The residents of the heavily African-American neighborhood had also, by no accident, been precluded from getting home loans that would have helped them buy their own homes. (Meanwhile, racist homeowner groups in booming nearby suburbs like Palo Alto were also working hard to ensure that "white flight" from the city stayed white.)

Starting in the 1920s and 30s, federal housing agencies distributed color-coded "residential safety maps" so banks could identify the best places to back mortgages. Areas with old buildings or the "threat of infiltration of foreign-born, negro or lower grade population" like the Fillmore were outlined in red, a warning against granting loans there.

"My mother tried to buy our first house in Alamo Square, near the Painted Ladies," said Fillmore native Rhonda Scott in "I Am San Francisco," an exhibit at the Main Library's African American Center. "But the banks wouldn't give her the loan. The sellers wouldn't sell to her."

Although some black Fillmore residents were homeowners, redlining prevented most from borrowing money to rehabilitate aging buildings. As a result, many accepted buyout offers from the redevelopment agency and left the neighborhood.

Boosters Tout Health, Safety Benefits Of Redevelopment

The same day the Planning Commission's proposal was released, inspectors dispatched by District Attorney Edmund G. Brown discovered "dozens of serious fire hazards" while inspecting Fillmore district buildings, reported the Chronicle. A task force of health and fire inspectors was created following a report by Brown declaring there were "100,000 violations daily in San Francisco of the State housing act and fire, building, health and safety codes."

Improving public health and safety were central tenets of urban renewal, and tenants and city planners agreed that living conditions in many Fillmore buildings were suboptimal.

The area was responsible for one-fifth of the City's tuberculosis cases. Inspectors found trash accumulated in backyards and hallways, poorly maintained fire escapes and electrical wiring, and that many single-family flats had been illegally subdivided into boarding houses with single rooms.

"A serious blaze, getting out of hand in a high wind, might start a conflagration that would sweep the district like a prairie fire, perhaps taking a toll of lives as great as that of the fire of 1906."1947 Planning Commission report

The report characterized the Fillmore as a magnet for crime, noting that the per capita outlay for police services was $23.28, "compared with 26 cents in the Marina district, a 'good' area of similar size."

Beyond physical dangers, the report suggested that residents of the blighted zone were also falling victim to moral decay. There were "71 bars, 45 liquor stores, numerous smoke shops and magazine stands suspected of gambling joints and bookies in disguise," not to mention "'hotels' that accommodate members of the 'world's oldest profession.'"

Rebuilding the Fillmore from scratch would also beautify the City, the report asserted, noting that the area's architecture was a hodgepodge of styles. According to a wrecking company that estimated demolition costs at $10,000 per block, homes built between the 1870s and the 1920s weren't "old enough to have historical interest" and "have little salvage value." (Today, one floor of a Japantown Victorian can be yours for $1 million.)

The report stated that many buildings within the blight zone could be rehabilitated, but City Attorney John J. O'Toole determined that the CCRA did not cover improvements to existing structures:

"I do not believe that the Act permits the redevelopment agency to undertake the remodeling and modernization of buildings if they are to be continued in essentially the same form and use as before."

"The Fillmore did not feel blighted to me as a child," said long-time resident Charles Collins in a 1999 KQED interview. "The only way that you can get to the issue of blight is to determine that the people who were living there, largely African American, had low incomes."

"You have to read into the idea that these absolutely beautiful Victorian buildings were also blighted because they were populated by black people," said Collins. "It's amazing to me when you look back at the amount of housing that was removed."

In 1948 and 1949, two successive City Attorneys found that the CCRA didn't permit the Board of Supervisors to control rents, set aside new housing for displaced residents, or prevent racial discrimination within redevelopment zones. When it came to resettling Fillmore residents, Morgan A. Gunst, the SFRA's first chairman, was unsentimental: "There's nothing sacred in a dirty little room in a slum area in which a man might be living," he testified in a state Senate hearing.

For months, the SFRA opposed non-discrimination policies, citing concerns that enforcing equality would discourage private investment. Herbert B. Henderson, the lone African-American agency commissioner, dissented. In May 1949, the Board of Supervisors passed a resolution condemning housing segregation; the redevelopment agency "agreed to follow the Board's recommendation," reported the Chronicle.

A Diverse, Integrated Neighborhood

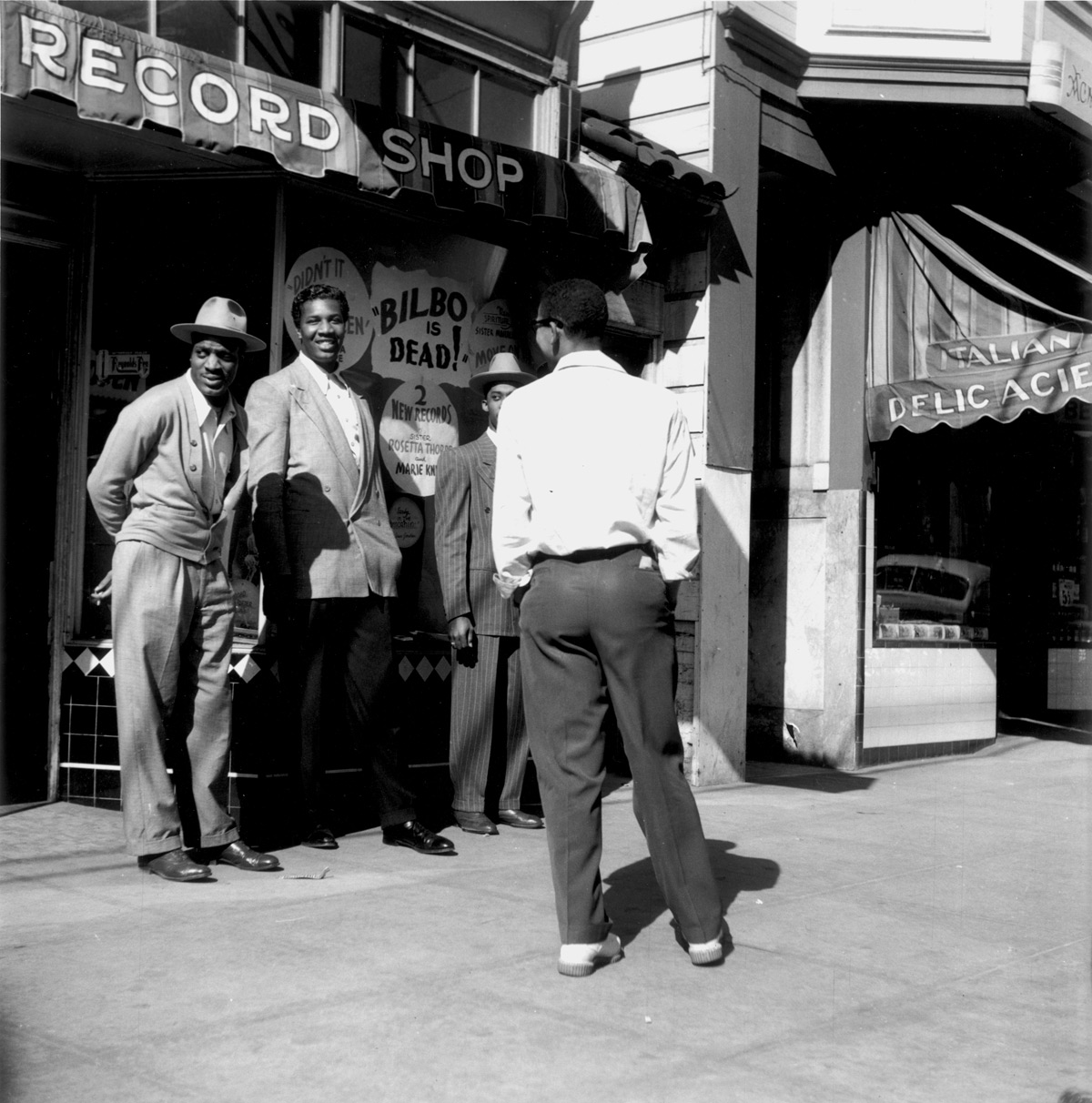

After the 1906 earthquake and fire, displaced residents and merchants shifted westward, transforming Fillmore St. into a thriving commercial district and cultural crossroads. An influx of Japanese-Americans concentrated north of Geary; synagogues, kosher butchers, bakeries and eateries signified a bustling Jewish community. A substantial number of Filipino, Mexican and Russian immigrants also lived in the district, making it one of the city's most-integrated neighborhoods.

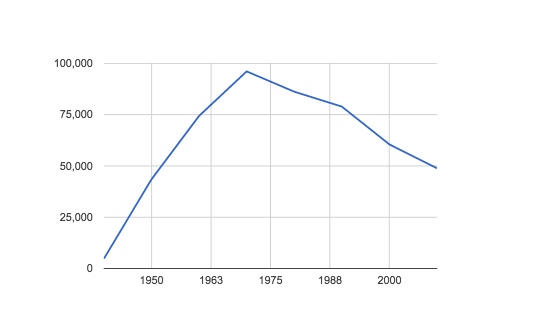

After African-Americans emigrated from the southeastern US to urban centers seeking work, San Francisco's black population went from 4,846 in 1940 to 43,502 in 1950. Many of these newcomers took jobs in the region's bustling waterfront and shipbuilding industries. Because of discriminatory housing practices, and housing that became available after the forced relocation of Japanese-Americans into internment camps, many black arrivals gravitated to the Fillmore.

By the 1940s, some Fillmore homeowners were buying homes in the suburbs. Thanks to the G.I. Bill and FHA-backed loans, white, middle-class earners could afford to buy new homes south of the city and in the East Bay. According to KQED's 1999 Fillmore documentary, 90% of tenants in the area were renting from absentee landlords.

For San Francisco's black population, the end of World War II brought high unemployment and uncertainty. Because most African-Americans earned blue-collar wages and weren't allowed to buy into suburban developments, flight wasn't an option. Instead of a "return home to the racist South," most newcomers decided to "make the best of it in a city where housing was rigidly segregated and the employment market was contracting," wrote author Paul Miller.

By 1947, African-Americans made up 26% of the Fillmore; 5% were Chinese-American, and 4% were Japanese-Americans. Even though two-thirds of area residents were white, the wartime black population "increased so rapidly that many persons now refer to it as a colored district," the report concluded.

The Fillmore Of Yesteryear

As its black population grew and nightclubs and restaurants started offering live entertainment in the 1930s and 40s, the Fillmore became the west coast's African-American cultural nexus. In its heyday, the district had "more than two dozen active nightclubs and music joints within its one square mile," according to Harlem of The West, a history of the era.

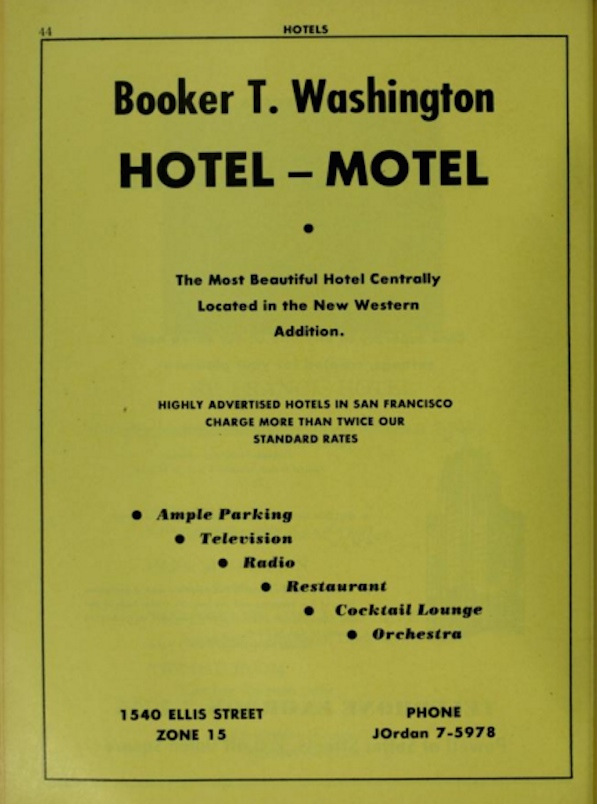

Because hotels were segregated, many performers stayed at the Booker T. Washington Hotel, a black-owned inn at 1540 Ellis St. The hotel "pulled in standing-room-only crowds every night with live music," said Jacqueline Chauhan, the daughter of the hotel's manager, in "I Am San Francisco."

The six-story, 125-room hotel hosted everyone from the Harlem Globetrotters to James Brown and employed a full-time staff of maids, bartenders and clerks, including Vivian Baxter, mother of renowned author Maya Angelou. "The cocktail lounge was called the Emperor and the dining room was called the Empress with chartreuse drapes and maroon carpets embellished with silver scrollwork," remembered Chauhan.

Once redevelopment began in earnest, the hotel was no longer viable; area clubs that attracted guests were razed or evicted, and adjacent buildings were marked for destruction. In 1966, the San Francisco Redevelopment Authority purchased the hotel for $300,000 with plans to use it as a temporary relocation center for displaced residents.

Two years later, the Booker T. Washington Hotel was torn down. "Without community support, the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency stepped in, and this landmark hotel vanished," Chauhan said.

"We played a great gig that night, and the very next day, they began demolishing the hotel," said musician Bobbie Webb in an interview for Harlem of the West. "It was so sad, because it wasn't falling apart. I guess it was just in the way. A little paint and it could have lasted for thirty or forty more years at least."

Like many razed lots in the Fillmore, the parcel remained vacant until 1983, when ground broke nearby for a new Safeway.

Tough Lessons

Residents in the area, centered around Fillmore Street near Geary, were frozen out of the planning process and for the most part were not able to participate financially in the benefits of redevelopment as it slowly rolled out. When new homes were eventually built, the former locals were often unable to afford them, and few returned.

The number of African-Americans displaced from the Western Addition as a result of urban renewal is unknown, but estimates start at 10,000 people. Less quantifiable is the cultural aftermath; a once-thriving district studded with minority-owned businesses, nightclubs and hotels in the heart of San Francisco now exists mostly in faded photos and oral histories.

Neighborhood groups trying to block freeways coming through their parks and backyards, other ethnic groups trying to stop redevelopment in their neighborhoods, and political activists of all stripes who were looking to make a local stand on issues in San Francisco found common lessons in the redevelopment saga playing out before their eyes in the 50s and 60s.

The city government couldn't be trusted to look out for diverse local interests, they felt. In the "defense of space," suburban homeowners in western neighborhoods joined with gay rights activists in the Castro and Latino activists in the Mission among others to successfully push for district elections for the Board of Supervisors. The localized electoral blocks created by this system brought leaders like Harvey Milk to power and the movement kicked off the modern progressive era.

Broad fears over redevelopment also triggered a cascading series of regulations around housing and construction that all these decades later have generated one of the most complex approval processes of any city in the country.

In our next story, we'll explore the last days of Western Addition redevelopment in the 70s, what the local government is still trying to do for the neighborhood up through today, and the broader consequences for the city.