A lawsuit launched this week by opponents of the 5M real estate development at Fifth and Mission might seriously delay the project.

It claims the city didn't follow all environmental review and planning rules before approving the plans last year.

Whether or not the suit succeeds, it reveals the ongoing split in the neighborhood's Filipino community. Some are eagerly awaiting the promised benefits from the 5M Project, while others are spearheading the lawsuit.

We've been covering the saga of the development so far, focusing on the blow-by-blows of hearings and debates.

Below, we sit down with a variety of Filipino leaders around SoMa to understand what's causing the differences, and how the community is working to resolve them.

The Drama Last Year

Last September, the scene at City Hall was getting out of hand.

Hundreds of people, many wearing matching T-shirts emblazoned with slogans and call-to-arms, crowded in front of the Planning and Rec and Parks commissions as they decided whether to approve the plans for the multi-building development surrounding Fifth and Mission.

At one point, a group of protesters interrupted proceedings and began chanting, passionately, “Who are you building for?” while the commissioners and members of the public still eager to share their thoughts looked on. Eventually, though, after sheriffs were called in and protesters cleared, the commissions voted in favor of the project, ending a marathon session and clearing the way for the Board of Supervisors’ own vote of approval two months later.

For many, this represented the end of a process that began over eight years ago, when the 5M Project was first proposed, and that has since spurred a debate about how the city should handle development and gentrification, while protecting the groups and communities most vulnerable to both.

In particular, the Filipino community, which comprises a significant segment of SoMa’s population, has been very vocal about their approval — or disapproval — of 5M. Leaders and representatives have shown up to public hearings and meetings en masse to either voice their support for the project’s benefits or to appeal against what they see as yet another nail in the coffin for a community that has been threatened for years.

The lawsuit last week has once again revealed stark differences in how both sides perceive the future of development in San Francisco, as well as how they think their community should respond to interests, both public and private, that will affect them.

Empty Parking Lots

The 5M Project will be built on a four-acre plot of land that is currently home to office buildings and surface parking lots. Much of it can only be accessed by narrow alleyways — the seclusion lends itself to drug use, which is why it is not uncommon to find discarded needles and other paraphernalia on the ground. This level of underutilization, and the problems that it can cause, is one of the more obvious reasons why supporters are backing 5M.

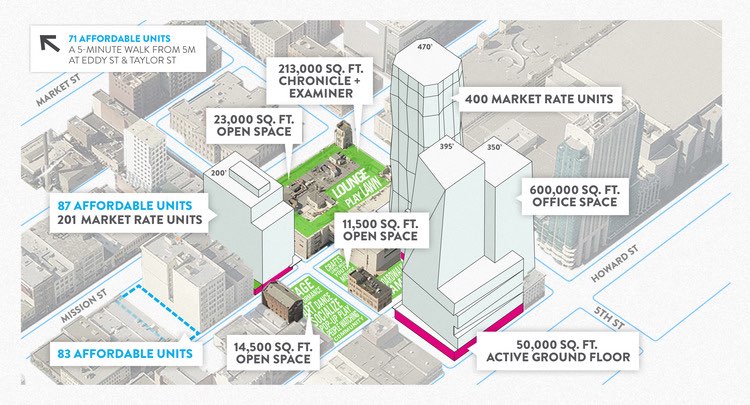

Forest City's latest map displays where it will build one new office and two new residential towers, as well as new public open spaces. The map also shows where the project's affordable housing contributions will be located. (Image: Forest City)

Forest City's latest map displays where it will build one new office and two new residential towers, as well as new public open spaces. The map also shows where the project's affordable housing contributions will be located. (Image: Forest City)

However, opponents of the project insist that they are not against development per se. In fact, many of them would be happy to see something built on this land, they just do not want to see it come at the expense of the surrounding community. This is where differences of opinion begin to emerge.

“When the wealthy residents and workers of the 5M residences and offices move in, naturally the neighborhood will change to suit them,” Vivian Araullo, the Executive Director of the Westbay Pilipino Center wrote in an email. “Businesses will sprout up to cater to the residents who can afford at least $1,784/month for a studio (the price of 5M affordable housing), not to the working-class Filipino family of five trying to cram themselves into a one-bedroom, $950/month rent-controlled apartment.”

Araullo and her organization were one of the most vocal, and visible, critics of 5M. (During the Board of Supervisors hearing in November, which ultimately gave the project its final green light, she spoke against it while surrounded by a crowd of Filipino youth.) She sees this issue as not only a failure of development that will push out her community, but as a systemic problem rooted in city governance.

“The whole process is skewed against vulnerable communities,” she said. “Just look at the reactiveness of legislation and even the affordable housing bond that was just passed. It will make you believe that the matter of development’s and new money’s impact on vulnerable communities was not really well thought out, or was barely considered.” She added: “Where is the voice of the underserved and communities of color in the envisioning of San Francisco’s future?”

Misha Olivas, the Director of Programs of United Playaz, a youth development organization in SoMa, sees things differently. She described how her and her organization came to support 5M after attending meetings with Forest City, the development corporation behind the project, and realizing how much of it would help the immediate neighborhood.

Representatives from neighborhood nonprofit United Playaz, showing their support for the project at the September hearing with Planning and Rec and Parks commissions. (Photo: Brittany Hopkins/Hoodline)

Representatives from neighborhood nonprofit United Playaz, showing their support for the project at the September hearing with Planning and Rec and Parks commissions. (Photo: Brittany Hopkins/Hoodline)

“The fact that a lot of the benefits are hyper-localized, that doesn’t always happen,” she said. “And the City isn’t always happy with that because they like to use that money city-wide, but a lot of these benefits — when it comes to the youth services, when it comes to the employment services — they’re going to be for SoMa residents.”

Olivas also cited these meetings as further proof that 5M and Forest City was a cause worth fighting for. Unlike the scores of smaller developers that are converging in SoMa and are purchasing properties and are forcing residents out, she explained, Forest City was actually taking the time to listen to the concerns of the neighborhood and get feedback. For her, gentrification and displacement was happening not because of large, special-use developments like 5M, but because of “piecemeal, one-plot projects that do their minimum 12 percent affordable housing and obey the code.”

In contrast, Forest City and 5M was offering her and her organization a chance to sit at the table and play an active role in the development of their neighborhood. This is why, she explained, she did not understand why people still campaigned against them, even after they offered 40 percent affordable housing. “To me, that’s symbolic,” she said, sounding exasperated. “It has nothing to do with logic.”

The Question Of Benefits

Perhaps the most contentious, as well as confusing, aspect of the 5M debate centers around what the development actually offers the community in return. The answer often depends on who you ask.

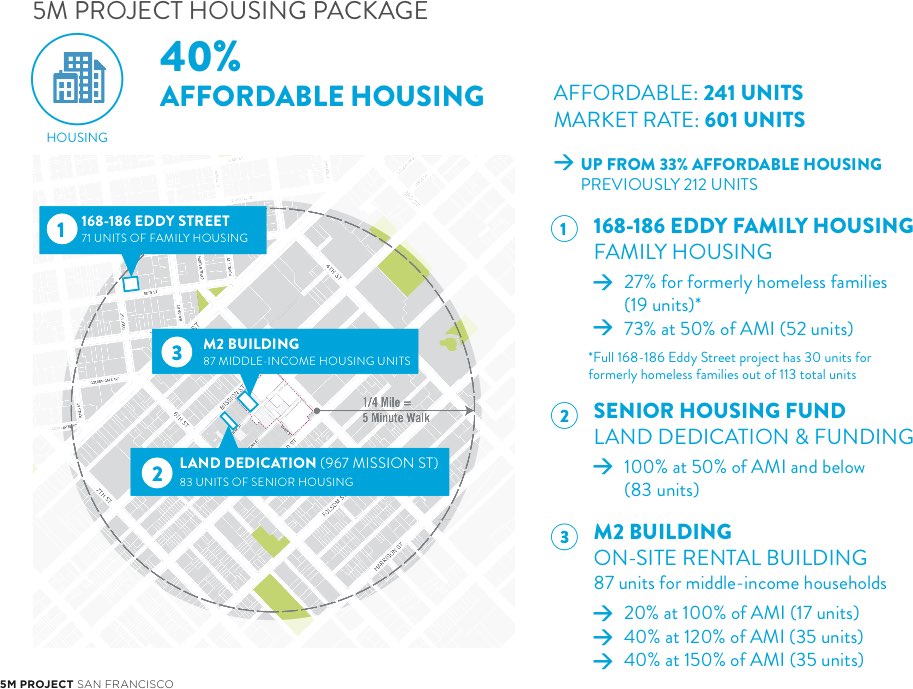

The final affordable housing package Forest City and city officials settled on. (PDF: Forest City)

“The 5M project has zero affordable housing” is the title of an op-ed piece published last November in the Examiner. Its author, Dyan Ruiz, a community organizer for the South of Market Action Committee, argues that Forest City’s claim of 40 percent affordable housing is “misleading and false.” Instead, the only on-site below-market-rate (BMR) housing consists of 87 units (out of 600) that are priced for people making 100 to 150 percent area median income, which translates to roughly $2,300 to $3,400 a month.

In order to arrive at the 40 percent figure, Ruiz explains, Forest City broke with San Francisco’s Inclusionary Housing Program by including the 71 BMR units that the Tenderloin Neighborhood Development Corporation will build at Taylor and Eddy using $18 million in funds from 5M. Furthermore, Forest City is also including 83 units that will be built on a plot of land located at 967 Mission Street, which they are donating to the city. All of this, says Ruiz, violates the law because inclusionary fees should go toward actual BMR units built by the developer, and Forest City is building none.

“The point is,” Ruiz said when contacted, “is that [Forest City is] supposed to mitigate different impacts. The office towers have a particular impact, the market-rate condo towers have a particular impact, and that’s why the City has different programs for each, and they’re basically confusing those programs and making it seem like they’re providing affordable housing, when really they’re just paying fees that they have to pay anyway.”

Ruiz is part of the coalition — which includes the South of Market Community Action Network (SOMCAN), Save Our SoMa (SOS), and Friends of Boeddeker Park — that has filed a lawsuit against the city over the approval of 5M. They are claiming that the environmental review the Planning Commission approved last September contained numerous flaws, such as out-of-date information regarding the project’s impact on traffic and a failure to show how the shadows cast by 5M’s buildings would affect surrounding areas, and are seeking to restart the approval process, which they think was rushed and inconsistent.

The newly-remodeled Boeddeker Park, one of the existing green spaces the coalition against 5M is aiming to protect from shadowing. (Photo: Blair Czarecki/Hoodline)

The newly-remodeled Boeddeker Park, one of the existing green spaces the coalition against 5M is aiming to protect from shadowing. (Photo: Blair Czarecki/Hoodline)

As an example, Ruiz mentioned the same community meetings that Olivas, of United Playaz, lauded: “Part of the issue that we saw with their community meetings is that they would meet with groups individually, so it was really hard to decipher what their project plans were, or what they were telling one group, or if they were telling another group something else,” she said. “That’s why we really were shocked when we saw what the project actually looked like.”

Even after they requested more inclusive community meetings, Ruiz said that Forest City presented information that was difficult to interpret, such as pictures of buildings that looked ten stories tall, rather than 47. Because of this, it was impossible for the public to fairly evaluate and comment on the project as it actually is, and so it deserves a reconsideration.

“We hope the judge sees that this was a rush job,” Ruiz said, “and that the city failed to do what was best for SoMa and the Tenderloin.”

However, for those that received benefits, such as residents of the Mint Mall, a mixed-use low-income residential building that borders the 5M development along Fifth Street, Forest City remains an engaging organization that listened to their needs.

Mint Mall at 953 Mission St. (Photo: Google Maps)

Mint Mall at 953 Mission St. (Photo: Google Maps)

Lorenzo Listana, a TNDC community organizer and resident, worked with the Mint Mall Resident Assembly to have a dialogue with Forest City and mitigate some of the negative aspects that the 5M Project might incur. Over the course of several meetings, they were able to agree on a number of measures, including limiting “disruptive activities,” such as pile driving, from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., and relocating residents who would be adversely affected. Forest City also agreed to donate $150,000 toward Mint Mall’s health and wellness program.

Listana attributes this success to the Mint Mall Resident Assembly’s willingness to work with 5M: “My position is that we should engage with these developers and have a dialogue. Whatever we need to do in order for us to stay in this neighborhood,” he said. “The other side who opposed it, they didn’t want to have a dialogue with those developers. We should be proactive. If you want the Filipinos to stay, and that is what I want, for the Filipinos to stay in SoMa, we should be proactive.”

Meanwhile, Araullo, of the Westbay Pilipino Center, sees such stories as a evidence of a “divide-and-conquer strategy and the power of agenda-setting fueled by corporate money.”

“It's easiest to prey on the vulnerabilities of underserved communities, and that's what's happening here,” she said. “It takes the form of possible donations. The help they want to give is tied to our support for their projects. But how can we continue to critically assess the impact of their projects on our Filipino families if their donation is tied to our support?”

Cracks And Connections

From its inception, 5M has been a massive and complex project, both in its developmental and architectural goals, as well as the ways in which it will change SoMa and the community that calls this neighborhood home. Olivas, for example, was quick to point out that, while the Filipino community is a large and significant presence, it is not the only community that will feel the effects of 5M: “United Playaz, we serve everybody, we don’t just serve Filipinos,” she said. “We had to look at this project as what does it bring to SoMa overall, and how does it help SoMa overall.”

Such complexity, and so many personal stakes, has not served the debate well. Supporters like Olivas admonish the misinformation that has come out of this, referring to people who have attended meetings “in tears” because they have heard 5M will consist of 100 percent luxury condos. On the other side, critics like Araullo lament those organizations that have “fallen victim” to corporate money and interests.

Still, no one thinks the divisions and disagreements that have emerged during the 5M debate will be lasting, or are even that significant now. Araullo emphasized that, while the two sides have parted ways when it comes to the inevitability of gentrification, “no community would willingly say yes to being displaced and disempowered” or that “gentrification is right or just.”

Likewise, both Listana and Olivas spoke to their continuing efforts to reach across the aisle and create a dialogue so that the Filipino community can preserve their place here and move forward. “5M is just one project,” Listana said.

Perhaps most optimistically, however, especially as she and her coalition of organizations prepare to present their lawsuit against the City, was Ruiz, who said she believes 5M has actually helped unite the Filipino community in a way it has not seen in years. “It has helped give people something to fight for,” she said. “It also put to question why the establishment of the Filipino Cultural Heritage District has been on the backburner for several years.”

“I think that it has been a wake up call for everyone to get involved in whatever way that they could,” she added. “So in that way it’s actually strengthened the community a lot.”