In 1982, Patrick Henry moved to San Francisco to open a new location of Superstar Video. A newly out gay man who had turned away from his former life as a born-again Christian, Henry had been working at Superstar's flagship store in his hometown, Philadelphia. But when he first opened the doors at 4057 18th St. (which is now home to Chaps), he had no idea just how popular the shop would become.

The AIDS epidemic had begun prior to Henry's arrival in the Castro, but the worst was yet to come. Henry's store quickly became a lifeline for many men battling the disease.

"The timing [of opening the store] could not have been better," Henry, now 55 and a longtime HIV survivor, told us. "AIDS devastated the entire community, and this enhanced the need for home entertainment, with its delivery of the distinct pleasure of seeing old favorites and new films in your own home. This was desperately needed by so many who became sick and bedridden."

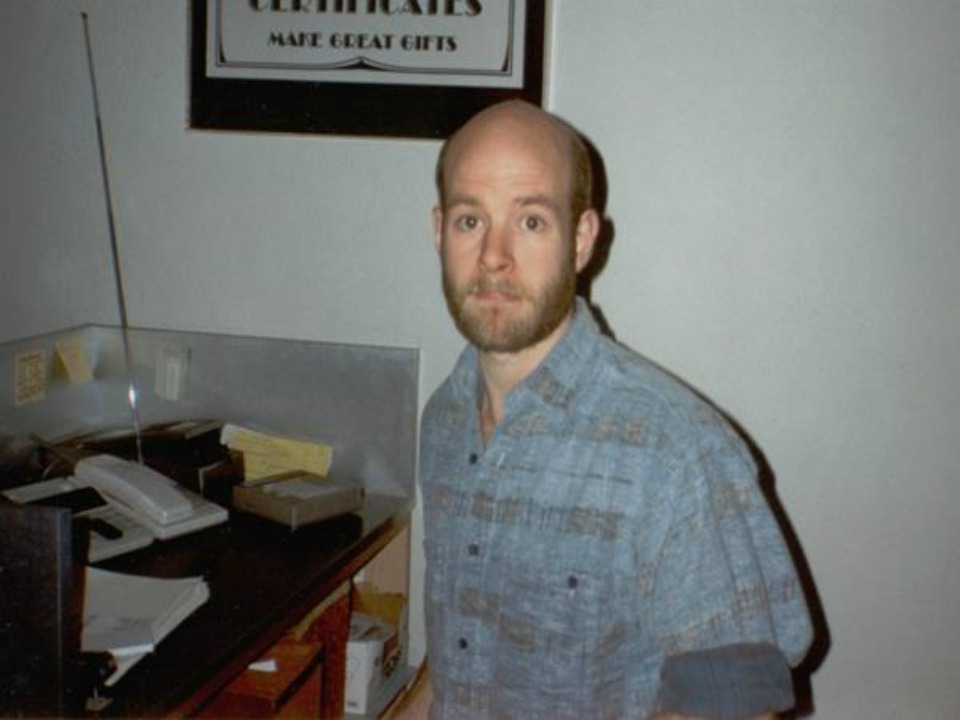

Patrick Henry at work in the store's early 90s heyday.

Henry took great pride in stocking every LGBT-centric film he could find at Superstar. Cult classics like Cruising, The Boys in the Band and Myra Breckinridge could always be found at Superstar, even during the years they were out of print.

Superstar also carried one of the neighborhood's most extensive collections of gay porn, which Henry said was important for many gay men who were avoiding sex as HIV and AIDS swept through the community. "Porn films quickly helped to promote the use of condoms, sexually glamorizing, and normalizing, their own essential part of our post-HIV sex-lives," he said.

Henry himself moved to the Castro in 1986, and two years later, he convinced Superstar's owner to relocate to a much larger location at 3989 17th St., next door to Orphan Andy's. (These days, Wild Card occupies the space.) Over the years, celebrities became part of the crowd: Sir Ian McKellen, authors Armistead Maupin and Anne Rice, and other notable names regularly rented videos at Superstar.

Although Henry loved his job, he admits that life in the Castro could sometimes be intimidating. "All that witty gay banter, stylish clothing, and those hairstyles!" he recalls. "As a nearly bald, quiet young man, I did feel terribly out of place at times. However, I shared the spirit of activism, which unified so many of us in those days. And I worked a lot, too, which kept me remarkably busy."

The tragedy of the ever-escalating AIDS epidemic also left an indelible impression. Death was all around him. "Other tenants in the building where I resided, co-workers, employees, customers, community leaders—all were dying at ever-increasing rates."

These losses motivated Henry to make Superstar a dedicated, active participant in the community. Superstar sponsored The Beeches, a local softball team, and allowed the then-emerging Gay and Lesbian Film Festival (now known as Frameline) to set up a ticket kiosk in the front end of the store. Henry advertised in all three of the local LGBT publications, and promoted HIV awareness and tolerance in his radio spots. "We contributed every time something was requested," he said.

A 1988 TV spot for Superstar Video, with voiceover by Henry.

But as the crisis escalated, Henry decided that he needed to take action to showcase what was going on in the community. In 1988, he launched Community Action News, a 60 Minutes-style news program that aired on local public access television. Henry, who still had his day job at Superstar, moonlighted as producer, editor, and host.

Though the show only ran for 18 months, it captured some of the most important moments of the era. Henry's footage of the 1989 police sweep of the Castro is now part of the archives of the GLBT Historical Society, and, "much to my amazement, is routinely shown on monitors at the GLBT History Museum in the Castro," he said. The video captures what Henry calls "disorganized, aggressive" police tactics, highlighting false police reports made by officers that night.

Another notable CAN report challenged the Chronicle's 1988 declaration that the Castro was becoming less gay. "The newspaper implied that families were moving into the area, due to vacancies caused by those who were lost to AIDS," he said, but that wasn't actually the case.

Though Henry stopped making CAN in 1990, he continued to support other Castro filmmakers. In 1994, Superstar signed on as a founding supporter of the documentary The Celluloid Closet, a history of LGBT themes and characters in the movies. Producers Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, who had won Oscars for The Times of Harvey Milk a decade earlier, thanked the store in the film's closing credits.

Henry has seen a lot in his more than three decades in the Castro. "Although change is inevitable, the Castro remains very gay-centric," he observed. He recalled some of his favorite hangouts from years past, namely 440 Castro, which was a bar called The Bear Hollow. "It was one of the least cliquish gay bars, so I was comfortable there; the bartenders kinda befriended this video nerd from Philly. But by the '90s, even I began to 'sow my wild oats,' as that saying goes— at places like the old Badlands, the Phoenix, and the Detour."

He also enjoyed several restaurants that once graced Market Street. "There was The German Oak, and that remarkably inexpensive Scandinavian place with the prepared food, which they generously spooned onto your plate from behind the counter," he remembers. "They even sold wooden shoes there, if I recall."

These days, Henry is happy to live a quiet life of retirement. He still occasionally attends rallies, and he's now in his sixth year of volunteering as an HIV-AIDS test counselor at Strut (formerly Magnet), an organization that demonstrates "the LGBT community's remaining vitality and the neighborhood’s centrality," he said. Strut now occupies the space at 474 Castro St. that used to house Superstar's third and final location. It moved there in 2005, the same year that Henry retired, and closed in 2014.

While Henry is confident that the Castro will remain a safe haven for LGBT people as it continues to evolve, he acknowledges that the need for a mecca like the Castro may not be as great as LGBT people continue to find more acceptance in the mainstream.

"Besides, any attempt to move to SF these days requires preparing for an expensive financial commitment before being able to settle here," he points out. "As we all know, this is not a town for anyone who doesn't arrive with lots of financial support, or having first secured a high-paying job."