We're revisiting some of our favorite local history stories to give new readers a look back. This story, originally published in August 2014, looks back at a long-gone ballpark at Turk & Masonic.

As the city says goodbye to Candlestick Park, it's worth remembering that this is not the first fog-covered monstrosity to provide a home for local professional sports.

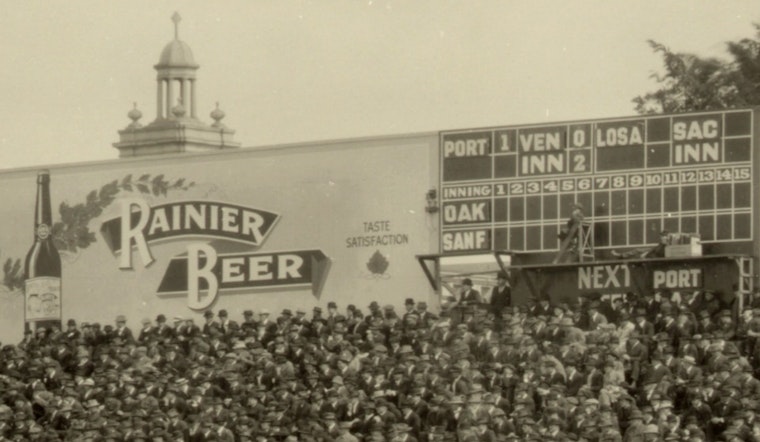

San Francisco has of course been dotted with other grand stadiums over the decades. But long before the Giants' era, the San Francisco Seals spent an unusual 1914 season way out west of Divisadero—at Ewing Field, a state-of-the-art facility at Turk and Masonic built by then-Seals owner James Calvin Ewing.

The stadium was touted as the city’s first fireproof ballpark, a popular claim in the wake of the 1906 earthquake and subsequent fire. It cost roughly $90,000 to build at the time (that would be a little more than $2 million today), and was opened with great fanfare, complete with a motorcade down Geary Boulevard and dedications by a who’s who of local politicians. 18,000 people attended.

In one contemporary local news article, Greg Gaar wrote that a horseshoe-shaped flower arrangement bearing the words “good luck” was knocked over during a ceremony in which a time capsule was buried beneath home plate.

If the Titanic-like announcement of the stadium's immunity to fire weren't enough, this ominous occurrence might now be seen as a harbinger. The stadium was beset by problems starting with that first game, when the Seals lost to Oakland—then the worst team in the Pacific Coast League.

The biggest issue faced by fans and athletes at Ewing Field was the fog. Long before Karl the Fog joined Twitter, the familiar cloud layer would bathe Masonic Avenue for much of the year, creating challenging conditions for players on the field.

"Pete Daly, a centerfielder, had to build a fire with newspapers to keep warm while patrolling a beat," Chronicle writer Will Connolly observed in a 1938 article looking back at the stadium's history. "Elmer Zacher, outfielder for Oakland, was so confused by the fog that they dispatched a mascot from the bench to inform Elmer the side had been retired and it was his turn to bat.”

Connolly also noted that it was extremely easy to sneak into the stadium or simply watch games for free from the top of nearby Lone Mountain (if you could see through the fog, of course).

Immediately after the 1914 season, Ewing sold the Seals to the Berry brothers, who owned league rivals the LA Angels. These fellows from down south determined the weather to be entirely too inclement for their newly purchased team, and negotiated the full purchase of better-known Recreation Park—from which the Seals had originally moved because Ewing didn’t want to share ownership of the field with the owner of Oakland’s baseball team. Apparently, some rivalries run pretty deep.

After the sale, Ewing Field was used for a variety of events, including circuses, operas, boxing matches, and football games.

However, in 1926, just 12 years after the first pitch was thrown at Ewing, the stadium burned down, taking a large chunk of the neighborhood with it.

Once heralded as “fireproof," the stadium was set alight after someone watching an amateur baseball game dropped a cigarette into the wooden bandstand. Strong winds fueled the blaze, and an AP article from June 5th, 1926 reported that the damage was estimated to cost roughly $207,500 at the time.

From the article:

"Carried by a stiff trade wind over Calvary cemetery, a distance of five blocks, embers from the Ewing Field Blazes furnished thousands of torches that fell on wooden roofs and started numerous small blazes…a number of wooden homes surrounding the field went up like so much tinder and householders, caught unawares by the quick spread of the blaze, escaped without hats or coats in most instances. The water mains in the vicinity of the Ewing Field were unable to furnish sufficient water to meet the demands of the firefighters, and the auxiliary salt-water system, built for fires of major proportion in the downtown area, was out of reach."

The field was vacant from 1926 to 1938, when it was demolished to build 95 new homes. Today, the last remaining vestige of Ewing Field can be found just west of Masonic, between Turk and Anza, in the form of the street Ewing Terrace.

Despite its ill-fated tenure on Masonic Avenue, Ewing Field may have brought to baseball something that places us all in its debt. In his 1938 article, Connolly wrote:

"The Smithsonian Institution will be interested to know that Mac McCormack sold the first hot dog from a portable stove in the history of American baseball at Ewing Field 24 years ago. The event was so important that Mac rehearsed for three days before the formal opening of the new park, to prevent the possibility of the alcohol stove blowing up the bleachers. In that dim age, the indigestible frankfurter, fried in olive oil, was a dangerous experiment, although the lowly provender has since become a staple food at sporting events."

So, the next time you bite into a ballpark hot dog, you can think about the brief but colorful history of Ewing Field. (And be thankful that stadiums are no longer built out of wood.)