There was a lot to be afraid of in the 1970s and early 80s—the oil crisis, increases in crime, nuclear annihilation. But for San Franciscans, the biggest threat came from inside, not outside, the city; a force that infiltrated homes, broke apart families and consumed their vulnerable youth. Religious cults had taken hold of San Francisco.

Cults—organizations of religious worshipers whose veneration revolve around a charismatic figure that offers salvation and acceptance based on concepts outside of mainstream religion—actually have a long history in the Bay Area ("Founding New Religions," SF Chronicle, July 12, 1908). The Psychical Researchists of Berkeley and Oakland’s Mazdaznanists, who believed that heaven could be obtained through proper harmonious breathing, were some of the first to appear in the first decade of the 20th century. And where there are cults, nefarious and illegal activities are rarely far away.

In 1910, Henry Yamaguchi, a religious zealot of a Shinto cult led by Shusehu Suto, a Japanese priest and self-proclaimed relative of the Emperor of Japan in charge of a mission at 1915 Bush Street, was accused of killing the Kendall family—whose residence was the only obstacle to the construction of a new temple for Suto ("Yamaguchi was a Shinto Fanatic," SF Chronicle, August 7, 1910). Suto, himself, was tried for felony embezzlement in 1908 but escaped conviction due to a hung jury.

Defrauding their followers landed William Riker’s Perfect Christian Divine Way cult in hot water with the government regularly in the 1920s and 30s ("Authorities Scan Reports on Affairs at Riker's Colony," SF Chronicle, January 25, 1929). And the wife and son of the deceased founder of the “I Am” cult were two of 24 leaders indicted in 1940 for forcing members to liquidate $3 million of their personal investments to offer as “love gifts” to the cult ("'I Am' Cult Indicted for Mail Fraud," SF Chronicle, July 25, 1940).

I Am’s San Francisco “Temple of Instruction” at 133 Powell Ave. and school at 2311 Scott St. preached sexual continence and divorce (even among couples with small children) and “self-mortality,” the belief that the body literally ascends to heaven after death, leaving behind only a small residue of “unessential parts.”

By the late 1960s, San Francisco was a hotbed of people looking for something to believe in, the perfect hunting ground for cult leaders. Charles Manson met 19-year-old Susan Atkins in San Francisco in 1967, one of the followers later convicted for the Tate-LaBianca murders and sentenced to death.

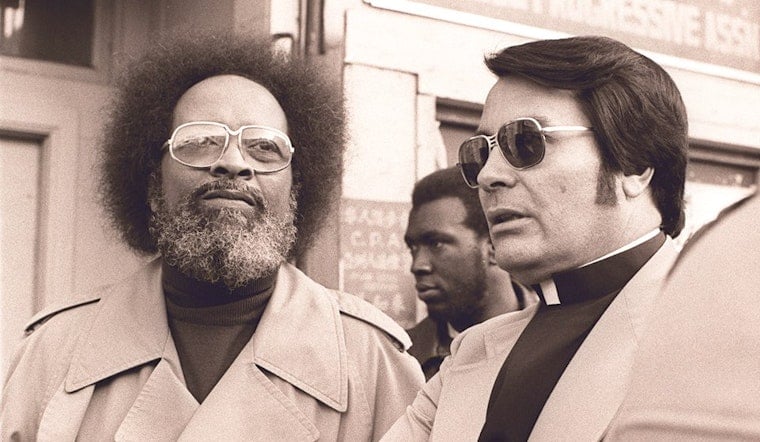

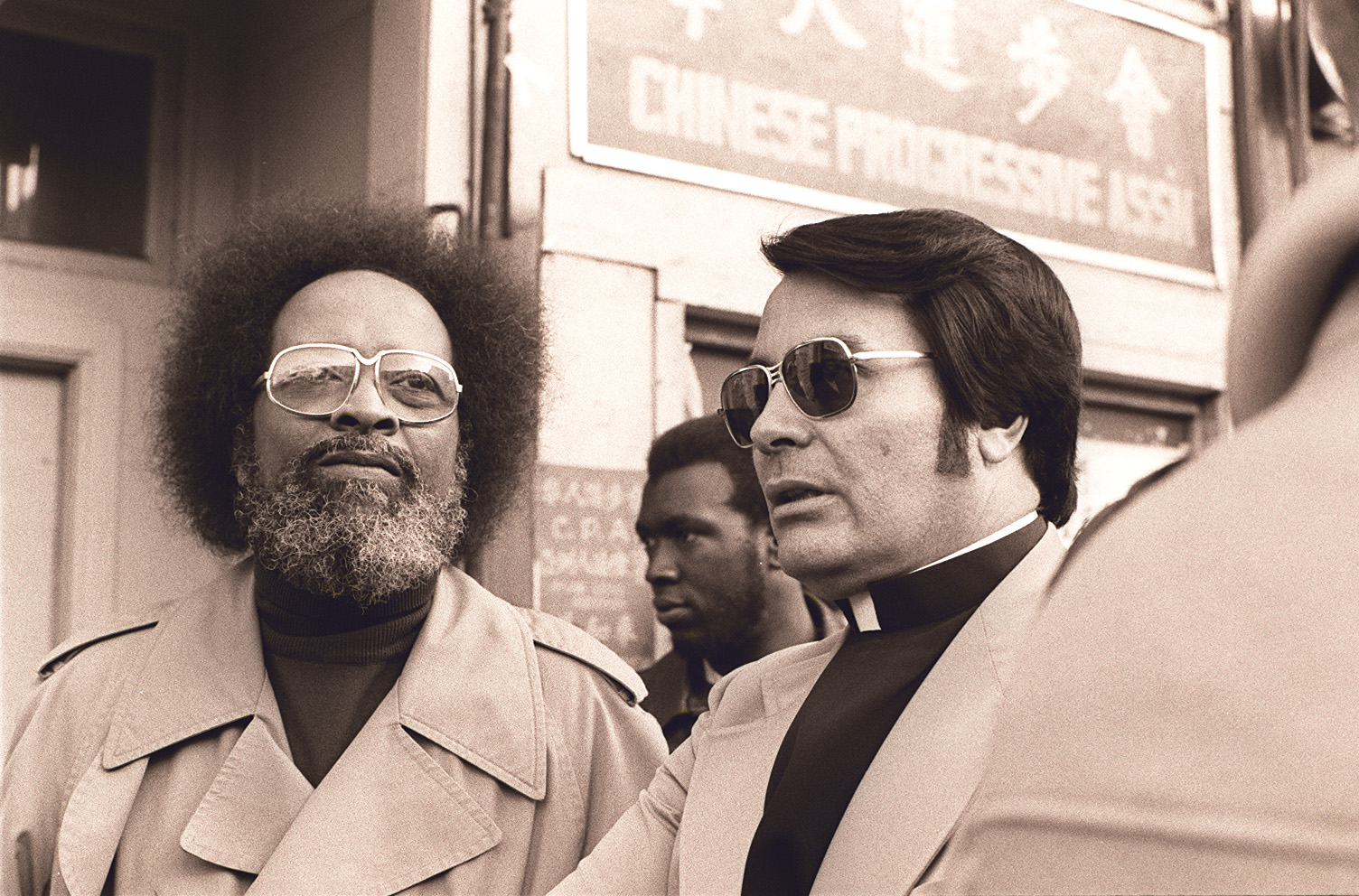

Jim Jones’ People’s Temple moved its headquarters to San Francisco in the early 1970s. Less than a decade later, in 1978, he incited 909 of his followers to commit suicide by drinking Kool-Aid laced with cyanide. Hare Krishna, the Children of God and the Unification Church of Sun Myung Moon (the Moonies) all operated in San Francisco during this period.

The call of cults was an epidemic that plagued mostly young adults. Isolated from friends and family, recruits were wooed by charismatic leaders (or their surrogates) preaching ultimate love and understanding. New members brought into the fold gradually lost their autonomy as the leader dictated where they could go, what they could spend their days doing and who they could speak to. Leaders claimed control over sexuality and marriage and, in some cases, perpetrated rape and violence against members.

As their children disappeared, San Francisco families were desperate for intervention. In 1978, just a month before hundreds of San Franciscans were killed in the Jonestown massacre, the San Francisco Chronicle published a plea for parents to be patient with their “cultist” children and criticized the “deprogramming” movement in which cult members were kidnapped and broken down over several days so that they could be returned to society ("Message to Parents of Cultists: Be Patient," SF Chronicle, October 8, 1978).

Many cult members were terrorized by the threat of deprogramming and som—like Brenna Steinberg, a 20-year-old Moonie who was “beaten, insulted, cursed and kept awake for five days by religious ‘deprogrammers’ hired by her parents” in 1981—were forever changed by the threat posed by their desperate families ("The Battle for Young Minds—Cults vs. Deprogrammers," SF Chronicle, April 15, 1981). Deprogrammers were given license by families to do anything they could to “save” cult members, including violence, shackling and forced druggings. For all their efforts, many members returned to their cult after deprogramming, now more convinced their biological families, not their religious ones, were dangerous or corrupt.

San Francisco’s cults too, were not particularly successful in the long run. Despite predictions that they would grow in strength over time, an estimated 75 percent of cult members dropped out after their first year and reintegrated into society, making the model somewhat unsustainable ("Message to Parents of Cultists: Be Patient," October 8, 1978). Which is not to say that religious cults don’t still loom large. But, with large-scale fundamental terrorism dominating today’s fringe religious landscape, the days of the Moonies and Hare Krishnas look downright sunny.