Last month, we revived the story of the San Francisco Tape Music Center, a revolutionary music space started by a group of electronic composers in the 1960s, and located at 321 Divisadero St. Today, we pay homage to one of the Center's founding members.

Pauline Oliveros, one of the most radical and outspoken composers of the 1960s San Francisco avant-garde, passed away last Friday. She was 84.

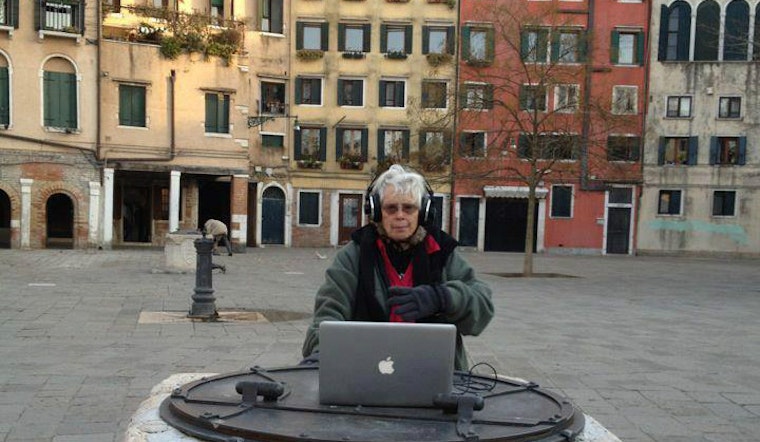

Oliveros is best-known for her philosophy of “deep listening,”which she developed in the ‘80s and promoted through workshops, books, and records by her Deep Listening Band. "Hear with your ears, listen with your heart” was her credo. Under Deep Listening, anything can be music: the hum of a fridge, the din of cars, the chatter of crowds. If you want it to be music, it’s music.

But long before developing this philosophy, she was one of the most radical composers of a scene that included better-known luminaries like Steve Reich, Loren Rush, and Terry Riley.

Born in Houston in 1932, Oliveros demonstrated musical skill as early as kindergarten. In an American Public Media interview, she recalled: “I’d always go for the drum in the cabinet, and the teacher would always take it away from me and give it to a boy and give me a kazoo.”

While studying at San Francisco State University, she bonded with prominent avant-gardists like Riley, trombonist Stuart Dempster (with whom she’d play in the Deep Listening Band), and Morton Subotnick, founder of the San Francisco Tape Music Center at 321 Divisadero.

Oliveros crafted many of her best-known compositions at the Tape Music Center. When it moved from Divisadero to Mills College in Oakland, Oliveros—who taught at Mills at the time—served as its director. It survives to this day as the Contemporary Music Center.

In 1967, Oliveros accepted a teaching position at University ofCalifornia, San Diego. She held this position until 1981, when she moved to Kingston, N.Y. She lived there until her death.

Oliveros worked in tape and sampling—unusual, scarcely-explored media in the 1960s —in crafting exploratory, uncompromising pieces that ranged from noisy drones and sound collages to orchestral works of stunning beauty.Though she was skilled at multiple instruments, she is best-known for her work on the accordion, an instrument synonymous with “unconventional.”

She was also one of the most outspokenly feminist composers of her day.

Perhaps her best-known early piece, “Bye Bye Butterfly” (1965),treated a sample of Giacomo Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly to bid farewell to both the music and the institutionalized sexism of the 19th century. In 1970, she wondered why there were no “great” female classical composers and wrote a New York Times op-ed criticizing the chauvinism of the classical music canon. The next year, she came out as lesbian in her Sonic Meditations in Source magazine.

Perhaps her most explicitly pro-woman composition is 1970s ToValerie Solanas And Marilyn Monroe In Recognition Of Their Desperation, an orchestral piece in which she empathizes with both the would-be Warhol assassin and the then-recently-deceased film superstar.

“Marilyn Monroe had taken her own life,” she wrote. “Valerie Solanas had attempted to take the life of Andy Warhol. Both women seemed to be desperate and caught in the traps of inequality: Monroe needed to be recognized for her talent as an actress. Solanas wished to be supported for her own creative work.”

It’s easy to see why she might have identified with these figures, having experienced the hurdles of being a female creative since she was first denied a drum in kindergarten—and overcome them to become one of the most legendary avant-garde composers in America.

Oliveros is survived by her spouse, Carole Ione Lewis; her stepchildren Alessandro Bovoso, Nico Bovoso and Antonio Bovoso; her brother John Oliveros; and eightgrandchildren.