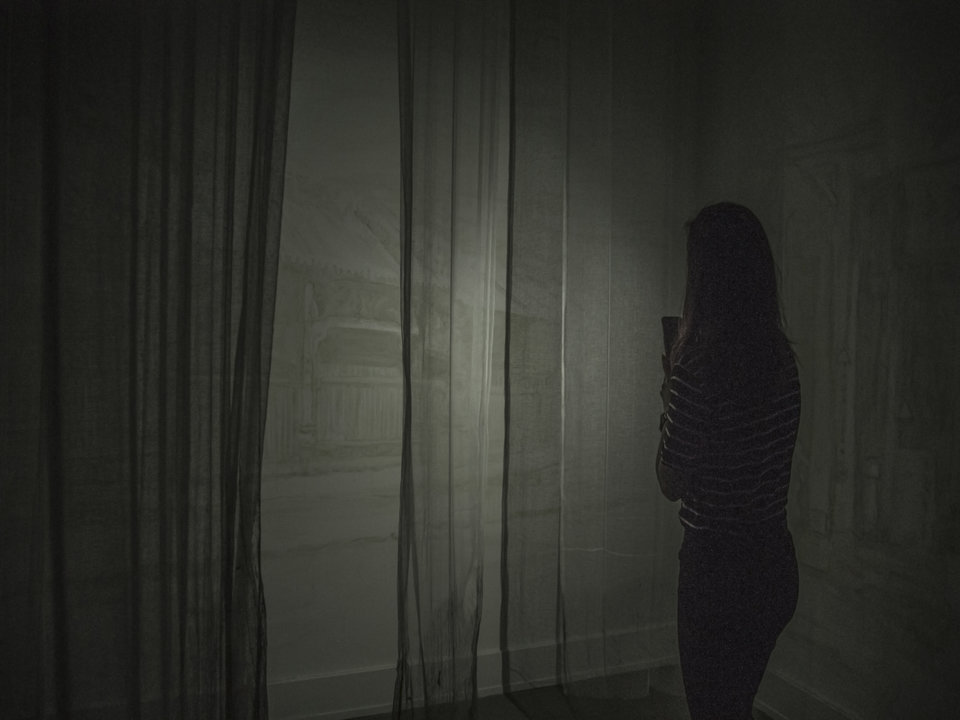

The Chinese Culture Center has debuted a new large-scale art installation that sheds light on the role a Hong Kong-based charity played in the history of the Chinese-American diaspora. Requiem, a commissioned piece by contemporary artist Summer Mei Ling Lee, will be on display until December 23rd.

At a media event held Tuesday, CCC Executive Director Mabel Teng spoke about the timeliness of the exhibition as the Trump administration moves to bar people from several countries from entering the country.

“What makes this exhibition so special is that it tells a really important story at a significant juncture in America," Teng said.

"We all know that this country is more divided than ever. There is the discussion on the Muslim ban that reminds us of the Chinese-American experience 135 years ago during the Chinese Exclusion Act."

The project stems from a part of Chinese-American history that is little spoken of.

After the 1882 passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act—which prevented immigrants from seeking citizenship and barred their entry for a decade—many Chinese had difficulty finding cemeteries.

Many immigrants preferred to be buried in their ancestral homeland, which further complicated the matter. Familial ritual worship along with secondary burial—a process of "exhuming the dead, cleaning the bones, and then burying them again—had a long tradition in Southern China as well," according to CCC.

To ensure that Chinese immigrant bodies made it back to China for burial, family members would pay a $5 fee to local family associations to coordinate with organizations in China.

Tung Wah Hospital—later renamed as Tung Wah Group of Hospitals (TWGHs) in 1931—was at the heart of the repatriation efforts and was responsible for many San Francisco-based Chinese immigrants finding their way home.

Ultimately, the group oversaw the return of over 100,000 "bone boxes" and housed them temporarily in the Tung Wah Coffin Home. The organization also facilitated family claims of the remains and would often deliver them back to hometowns and villages.

“They had no relatives in San Francisco because of the Chinese Exclusion Act," Teng said. "So where did these men go after they died? That tells the significant role and contribution of the Tung Wah Hospital."

After the group received someone's remains, they were transported to Hong Kong and stored safely "until their family came to reclaim them," said Teng.

It's on the occasion of the Exclusion Act's 135th anniversary that third-generation Chinese-American artist Lee began learning more about the hospital's support of local immigrants and how she could incorporate that information into the installation.

Lee traveled to Hong Kong this year, meeting with TWGH historians who shared the story of the hospital's efforts. On one visit, she visited the coffin home and opened one of the many unclaimed remains the organization continues to protect.

"This one," a CCC representative wrote in a statement, "like one-third of the boxes shipped over the seas from the United States, was empty—a ‘soul summoning box’ with just a name in it for an individual whose body was likely vandalized or in some way unrecoverable."

“I realized that there was something particular about my subjectivity as a descendant of Chinese immigrants that gave me a unique experience and it was my job to communicate that," Lee said.

The exhibit runs from October 26th–December 23rd and is openTuesday–Saturday 10am–4pm on the 3rd floor of the Chinese Culture Center (750 Kearny St. at Washington). Admission is free.