Some city residents still use them for commuting. Others avoid them—and the hordes of tourists waiting in line to ride for fun. But no matter your attitude, cable cars are a part of the city's landscape and appeal, and we decided to take a brief look at their history and some of the stories surrounding them.

One good source for details on the cable cars is Rick Laubscher, president of Market Street Railway. It's a volunteer-based advocacy group that's not connected to Muni, but it serves as the nonprofit preservation partner of SFMTA (more details are on its About page).

While cable cars were born here in the city—and are now a distinctly San Francisco treat—they were once a popular means of transit throughout the United States and the globe.

Powell Street turntable, early 1930s. (Photo: Market Street Railway)

The (possibly apocryphal) story is that Andrew Hallidie, a Scottish immigrant, got the idea for the cable car after witnessing a horrific accident in which a horse-drawn streetcar careened down one of the city's steep hills, killing the animal.

He already had some expertise with cables: "Hallidie was successful in the mining business with wire rope conveyors that would haul ore in buckets tied to wire ropes,” Laubscher told us. "He was in the business; he knew the mechanics. His contribution here was to move the machinery underground, and develop a device to attach and un-attach streetcars to and from this wire rope."

Hallidie landed a deal with the city to dig up the streets, lay the lines and offer a means of private transportation. As for when the first cable car ran, his contract stipulated he had to start August 1st, 1873, so many accounts use that date. But, Laubscher said, "you’ll still get a big debate among historians here if it was August 1st or 2nd."

Regardless of the specific start date, the use of cable cars spread like wildfire throughout the late 1800s. Joe Thompson, creator of the Cable Car Home Page—a wealth of information about all things cable car—has an extensive list showing where and when they operated. Locations ranged from Australia and New Zealand to Edinburgh and Glasgow in Scotland, to Liverpool and London in England. Here in the States, they were found in Chicago, Cleveland, Denver, Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, Portland, Seattle and many more cities.

Powell Street turntable. (Photo: Heather Moran/SFMTA)

Powell Street turntable. (Photo: Heather Moran/SFMTA)

"Cable cars spread out at first because they were better, economically, than horse-drawn railways," Thompson said. "You have to feed [horses] whether they're working or not, and you had to have a lot of horses, because they couldn't work all day, and they dump unpleasant stuff in the street."

But cable cars gradually lost favor because they were expensive; electric streetcars (such as SF's historic E-line and F-line, still running today) were much more attractive economically. Toward the turn of the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth century, most cable car lines began to shut down.

There were a few other stragglers besides San Francisco: a couple of lines in Seattle and one in Melbourne lasted until 1940, and Dunedin, New Zealand, kept three running into the 1950s.

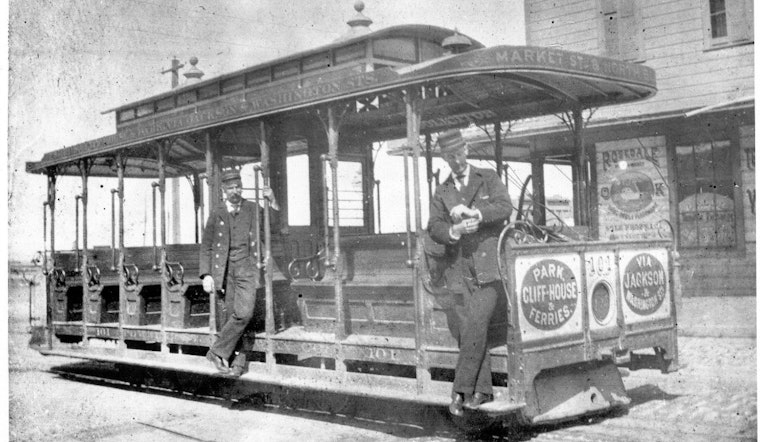

Sacramento-Clay Cable Car at Clay Street and Embarcadero, 1940. (Photo: Market Street Railway Archives)

As for San Francisco, it didn't even own any of its cable car lines until 1944, and cable cars remained privately operated here until 1952. The city took them over after the California Street Cable Railroad declared bankruptcy. "That’s when our namesake, the private Market Street Railway, merged with Muni and became part of the city," Laubscher said.

Cable cars came close to extinction in 1947, when then-Mayor Roger Lapham tried to shut them down and replace them with buses, due to concerns about operating expenses. But a feisty supporter, Friedel Klussman—who became known as the "Cable Car Lady"—saved them, and now, they're protected by city charter. The Hyde Street turnaround is dedicated to her, Laubscher said, adding that it was a "woman-led campaign at a time when women didn’t have any political power in San Francisco or anywhere else."

The terminus of the California Street line today. (Photo: Geri Koeppel/Hoodline)

Market Street Railway has worked with Muni to restore the paint on the cable cars to the various liveries’ authentic paint schemes from different times in history. "They’d been through about nine major livery looks in 128 years, since the Powell-Mason line opened in 1888," Laubscher said.

Now, the fleet has a car painted like the original 1888 livery, the yellow livery used in the 1890s, a bright red used just before 1906 earthquake, green used after the earthquake, and so on. The last gap in the collection will be rolled out later this year, so there'll be a full set representing all of the looks, Laubscher said.

“There’s a lot of detective work that goes on" to make all of the cars look exactly like they used to, Laubscher noted. Old photographs are typically in black-and-white, so finding out a car's color can be tricky; sometimes, they scrape through layers of paint to find the right shade.

"The Muni craftworkers do this job, and they do it really well," Laubscher added. "We provide them the paint colors and drawings showing the exact design. We research all this stuff and make sure we get it as accurate as possible."

Cable car 9, painted in 1920s livery, at Hyde and Chestnut Streets. (Photo: Market Street Railway)

Laubscher believes the cable cars should become more accessible to locals. "We are incredibly lucky to still have the cable cars today, and we ought to be paying them more attention," he said. "They should not be relegated to a Disney-style tourist attraction. They should be accessible to everybody, and remain an important part of transit options for San Franciscans.”

One reason many locals don't ride: high fares. Cable car fares used to be the same as Muni fares, but they were separated in the early 1980s. Back then, the Muni regular fare was 60 cents and the cable car fare was raised to $1—less than double a bus ride. Today it’s $2.25 for Muni and $7 for the cable car—more than triple. Only those with monthly Muni passes get to skip paying the $7 charge, something Laubscher thinks should change in favor of a discount for all local residents.

"You can’t even get a transfer from one cable car line to another," he noted.(Though some through the years have continued to call for eliminating the cable cars based on expense, Laubscher noted that all public transit systems in the country rely on subsidies, as do public roads.)

Last day of the cable car line that ran on Castro between 18th and 16th Streets, April 5th, 1941. (Photo: Market Street Railway Archives)

For more history and current updates on the cable cars, check out the Cable Car Guy site, which is updated frequently. It includes recent news about some cable car-related topics we've covered here on Hoodline, including new efforts to keep cable car riders and operators safe, and push to keep most vehicles off of lower Powell Street to reduce wear and tear on the cars.

Thompson's favorite book about cable cars and the one he recommends most is The Cable Car in America, by George W. Hilton. Many books about cable cars are also available in the San Francisco Public Library history room, Laubscher mentioned.

-2.webp?w=1000&h=1000&fit=crop&crop:edges)