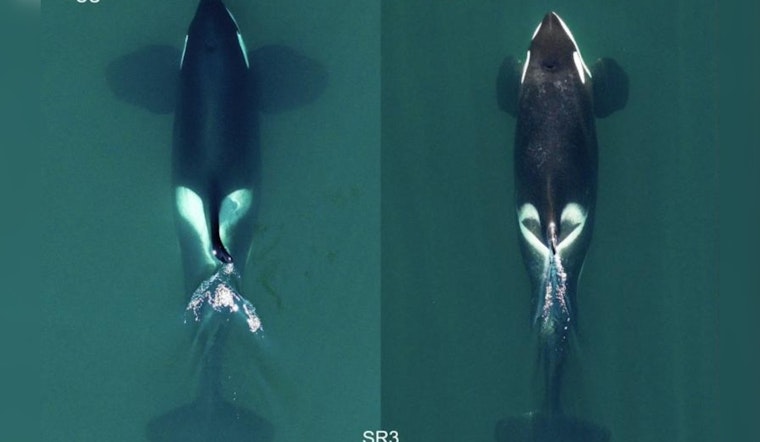

Ocean scientists have split the black-and-white world of the killer whales into new categories, as it turns out, there's more to these ocean predators than meets the eye. Researchers have identified what they believe are two distinct species of killer whales in the North Pacific, previously thought as one single global species known as Orcinus orca. Going beyond mere physical appearance, scientists have used genetic and behavioral evidence to differentiate between the two ecotypes roaming the Pacific coast.

According to a recent publication by NOAA Fisheries, these two ecotypes, known as resident and Bigg's killer whales, have long shown evidence of distinct populations, but only now have they been pegged as separate species. This discovery has its roots in the work of a Canadian scientist, Michael Bigg, who in the 1970s first noted that the two types didn't intermingle, despite sharing coastal waters – a key sign of being different species. This new realization not only pays homage to Bigg's insightful observations but also underscores the diversity of life beneath our ocean waves.

The team spearheaded by Phil Morin, an evolutionary geneticist at NOAA Fisheries' Southwest Fisheries Science Center, has brought clarity to the species question that had them stumped for nearly two decades. "We started to ask this question 20 years ago, but we didn't have much data, and we did not have the tools that we do now," Morin told NOAA Fisheries. "Now we have more of both, and the weight of the evidence says these are different species."

The research identifies residents and Bigg's killer whales as not just different in their hunting habits, with residents feeding on fish like salmon and Bigg's preying on seals and other marine mammals, but also as genetically disparate. Genetic studies suggest the two species likely split paths over 300,000 years ago, deriving from opposite branches of a killer whale family tree. As put by Barbara Taylor, a former marine mammal biologist at NOAA Fisheries, "They're the most different killer whales in the world, and they live right next to each other and see each other all the time. They just do not mix."

Recognition of these killer whales as separate species could have profound implications for conservation efforts, particularly for the Southern Resident killer whales, already listed under the Endangered Species Act. The separate species classification reaffirms the requirement for tailored protection measures for these distinct populations residing along the North Pacific Coast. As marine ecosystems continue to face pressures from human activity, these findings are a critical step in ensuring the survival of the oceans' most iconic inhabitants.