San Francisco, a city built mostly on sand dunes, grasslands, swampy creeks and rock, has more street trees than ever – above 105,000 at last count.

Its plan for caring for this urban forest, however, is a work in progress.

Many of the trees alive today were planted in the 20th century, particularly in the late '50s and early '60s. Maintenance costs grew along with the urban forest over the decades, but budgets started shrinking in the early '80s.

So the Department of Public Works has been steadily offloading care for individual trees to local property owners, citing budget cuts. And many of the trees the DPW does still care for get pruned, staked and otherwise maintained far less often than they should.

“Right now we're on a 10- to 12-year pruning cycle, on average, per tree,” DPW spokesperson Rachel Gordon noted. “We’d like to be at a two to five year cycle, but because of years of budget cutbacks, we’ve not been able to do as robust pruning or as frequently.”

Storm damage on Waller Street, December 2nd, 2014. Photo by Andrew Dudley / Hoodline

Storm damage on Waller Street, December 2nd, 2014. Photo by Andrew Dudley / Hoodline

In addition to suffering from this human neglect, the earliest generations of San Francisco's street trees are dying from an unavoidable cause — namely, old age. And trees of all ages are facing challenges from the increasingly extreme weather conditions associated with climate change.

The seemingly never-ending California drought has weakened many trees, drying out their roots and making their branches more brittle. When heavy rains soak the city’s sandy soil, and the wind picks up, more trees come down. The wind doesn't have to be hurricane strength, either; as Gordon told us, trees and branches start coming down whenever gusts go above 30 miles per hour.

Stormageddon Strikes

Unlucky locals had personal experiences with the combination of these issues in November and December of 2014. Tree limbs — or entire bodies — toppled throughout the city, occasionally falling on cars, fences, and buildings below.

Fallen tree on Waller Street, December 24, 2014. Photo by Paul W. / Hoodline

Fallen tree on Waller Street, December 24, 2014. Photo by Paul W. / Hoodline

For the property owners responsible for a tree, normal maintenance costs can run into the thousands of dollars, or require permitting and additional fees to remove. Tree stewards can also be held liable for the damage their street trees cause.

"My partner and I bought a house on 19th Street in the Castro in April 2013," reader Ryan P. related to us recently. "We were forced to pay over $1000 for sidewalk repairs needed because of root damage from the tree in front of our house."

To learn more about why so much tree care is required, we talked to horticulturalist Dr. Larry Costello of the University of California Cooperative Extension service for San Francisco. Pruning trees is an important aspect of keeping them healthy and safe in urban environments, Costello explained. Left to their own devices, trees can develop structural weaknesses that can cause them to topple to the ground.

Above, a city map showing current street trees, with green dots representing those the city maintains, and gray showing privately-maintained ones, via the Urban Forest Plan.

Above, a city map showing current street trees, with green dots representing those the city maintains, and gray showing privately-maintained ones, via the Urban Forest Plan.

Some trees, like many species in the now-dreaded ficus genus, naturally lose limbs when they reach a certain size.

“Trees aren’t perfect in terms of structural entities. Whether it’s the branches not being attached very well or the crown of the tree becoming imbalanced, trees can fall down even on calm days,” Costello said. “When the wind comes up, it increases the potential for a failure to occur. And urban trees need to be maintained to ensure that potential problems like conflicts between roots and sidewalks get resolved.”

Dr. Costello remarked that he’s worked with the DPW and city arborists, and that these local employees were quite knowledgeable about tree maintenance, but suffered from a lack of resources. “There’s much work to do, and not enough people to do it.”

The city plans to reduce the number of trees it maintains by transferring the rest to private owners, via the Urban Forest Plan.

The city plans to reduce the number of trees it maintains by transferring the rest to private owners, via the Urban Forest Plan.

DPW budget constraints have left a crew of 10 workers responsible for managing 105,000 street trees and fielding roughly 3,700 calls a year for urgent matters like broken branches and fallen trees. Because the staff is so small and the demand so huge, maintenance is often delayed, giving trees more time to grow, which results in larger pruning jobs required for each tree.

Meanwhile, private property owners might not prune trees properly after they take control. For example, topping a tree off (removing its central growth column) can make it direct too much energy towards side branches, which eventually get heavier than they otherwise would, and thus fall off more easily.

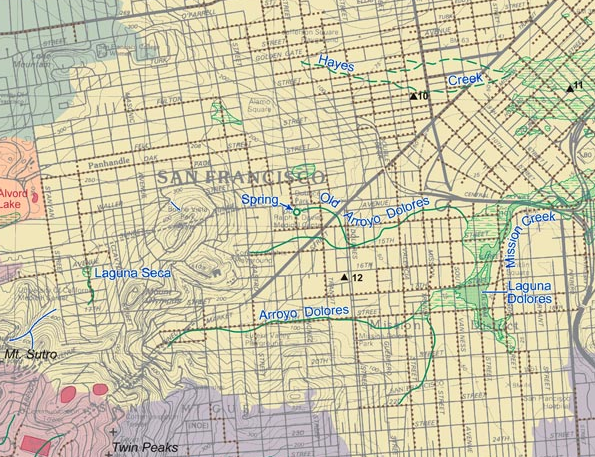

There can also be unseen circumstances impacting local street trees that are beyond a property owner's control. Some readers have been wondering if Waller Street’s many tree falls late last year were due to some strange water or soil history that made the ground extra soggy and loose. After all, there was once a wetland, a spring and a creek right in the area. In fact, an underground spring may have been discovered recently just two blocks away, with water bubbling up from a sidewalk at Haight and Divisadero.

A view of the local watershed as it existed before the city, via the Oakland Museum of California.

A view of the local watershed as it existed before the city, via the Oakland Museum of California.

With so many challenges both natural and manmade, there are ample disincentives for planting street trees in this city. But there are plenty of good arguments to be made for increasing the city's tree canopy, as well.

In Defense Of Street Trees

Trees are, admittedly, not a natural part of much of San Francisco. Hundreds of years ago, you could find some oaks, California buckeyes and maybe even a redwood or two tucked away near a creek. But mostly there were sand dunes, and assorted scrub brush and grassland similar to what can still be found along the coastal shores south towards Santa Cruz or north towards the Russian River.

There have been various recent efforts to return parts of the San Francisco landscape to something more akin to this natural environment. UC San Francisco almost decimated the old alien eucalyptus forest covering Mount Sutro in recent years, and only a protracted battle by fans and neighbors of the park preserved that unusual environment. The same sort of issue played out in Glen Park recently, when residents rallied less successfully to stop alien species from being cut out of Glen Canyon.

Historical map of San Francisco soil and water, pre-city, via the Urban Forest Plan.

Historical map of San Francisco soil and water, pre-city, via the Urban Forest Plan.

It’s a matter of perspective, as some pro-tree advocates might tell you. Which is more out of place here — the urban infrastructure of today’s city, and the million-odd people who occupy it every day, or a redwood that may naturally grow better further up the coast? Should we be reintroducing native North American plants that arrived here from the east coast 2000 years ago, or should we plant whatever trees are best suited to the climate and the various day-to-day needs of the modern city?

The specifics about which species should be planted, and where, remain an ongoing topic of debate. But there does seem to be widespread agreement that street trees in general are a desirable and worthwhile addition to the urban landscape.

As Dr. Costello reminded us during our conversation, they can help increase property values, provide habitat for wildlife such as birds, reduce wind speeds, and create cooling shade for homes and offices. Trees also act as filters for particulate matter that tends to float around cities, cleaning the air. And of course, they're a nice aesthetic addition to an otherwise concrete jungle.

View of San Francisco, formerly Yerba Buena, in 1846-7, via the Library of Congress.

View of San Francisco, formerly Yerba Buena, in 1846-7, via the Library of Congress.

Additionally, trees have (and generate) monetary value. If you include all 669,000 trees in the city, the total value is $1.7 billion according to a US Forest Service report. The trees provide an estimated $9.5 million in environmental and health benefits, and contribute $100 million to city property values.

The Future of the Urban Forest

You can read in detail about all of the arguments above in a new city-led report called the Urban Forest Plan published last year.

Created by city planners, the DPW and other experts, including the nonprofit Friends of the Urban Forest, the plan provides a well-illustrated, well-supported explanation of the history of San Francisco trees.

After running through the evolution of the urban forest from city founding through ficus plantings, it recommends taking care requirements away from private individuals and creating a citywide tree maintenance program of the sort that doesn’t exist because of the aforementioned budget problems. The plan would also increase the number of San Francisco street trees by 50 percent.

Where would the money come from? The report recommends that the city do a better job of tapping into existing governmental resources, getting more private donors, and maybe even crowdfunding online, but leaves the specifics up to policymakers.

A view of city street trees, if they were all maintained by the city as the Urban Forest Plan proposes.

A view of city street trees, if they were all maintained by the city as the Urban Forest Plan proposes.

The effort to find a solution is gaining new focus, especially as the cost to private property owners continues to rise. District 8 supervisor Scott Wiener has been working on the issue, and is currently putting together a working group to figure out funding possibilities. Comprised of many of the same groups that put together the Urban Forest Plan, along with other community and property owner organizations, this group will begin meeting next month.

This Urban Forestry Fund, in any form, would require the city to take back control of trees, and would cost at least $20 million annually. It would probably also require that old-fashioned form of crowdfunding, a ballot measure.

We talked with Wiener about what the funding structure might look like.

“A lot of ideas have been swirling around for a while,” he explained. “A parcel tax is one of the options. For many property owners, it’d save them money – they’d only need to pay $40 to $80 a year [for the parcel tax], which is a lot cheaper than paying arborists to come out to prune, or to get the sidewalk fixed.”

Wiener said another option is doing a “set-aside,” amending the city charter to require that a certain part of the general city budget goes towards tree maintenance. This is already done for libraries, children’s programs, public education, public transportation, and other city initiatives.

Street trees have received funding during San Francisco's more prosperous eras, but when the city has needed to balance its budget, maintenance has been cut in order to preserve the budgets of programs like the ones mentioned above. If trees were to receive set-aside funding, that allotment would be preserved in the face of any budget cuts, ahead of city programs that don’t have the same protection.

Or, Wiener adds, there’s the option of doing a blend: a parcel tax conditioned on a baseline of set-aside funding.

“However we do it, the most important thing is to actually have enough money in [the Urban Forest Fund] to solve the problem. There’s a temptation to do this, but just do it smaller, to not impact the general fund, to make it easier to pass – and it won’t be enough to actually solve the problem.”

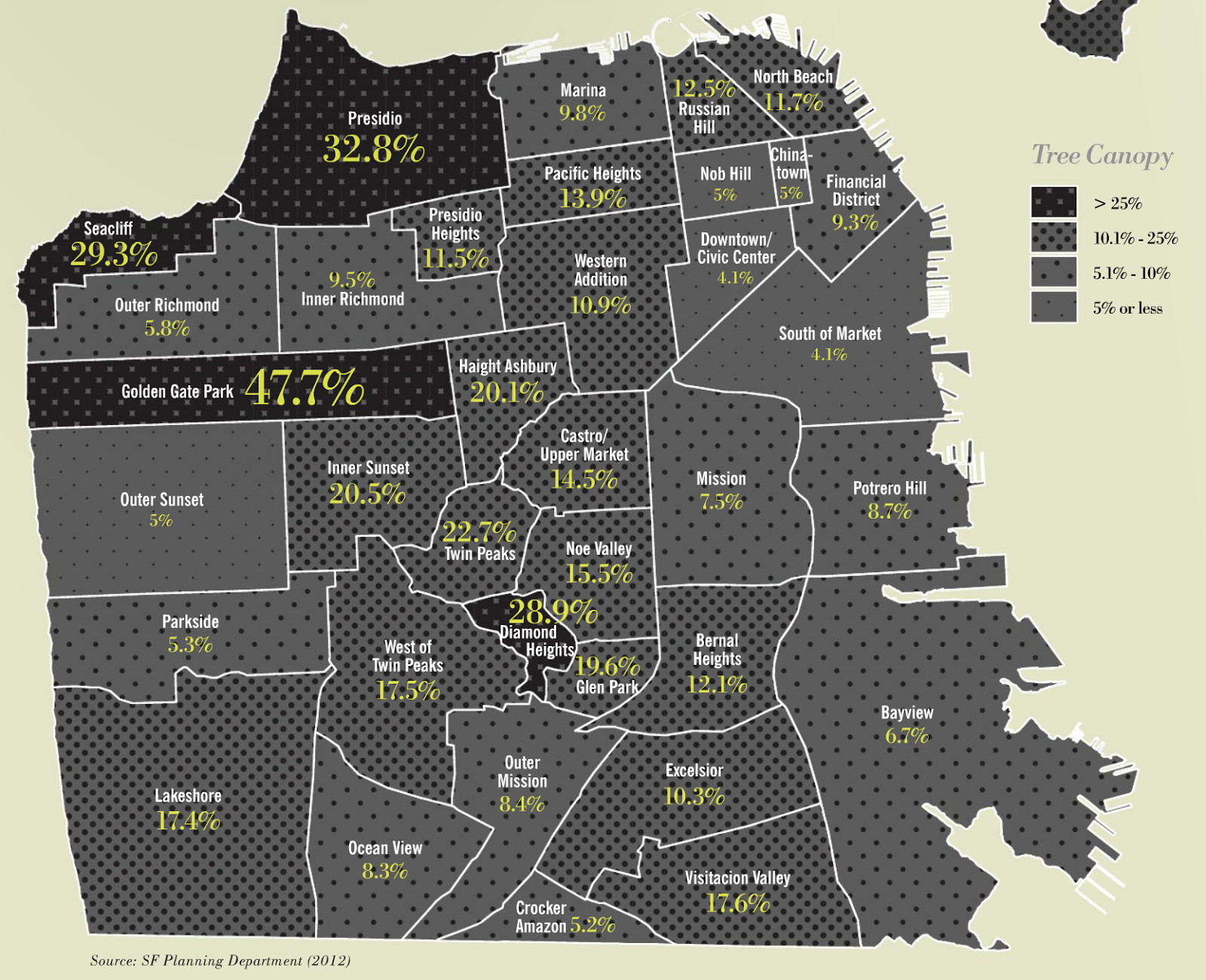

Tree canopy cover by neighborhood, based on SF Planning data in the Urban Forest Plan.

Tree canopy cover by neighborhood, based on SF Planning data in the Urban Forest Plan.

We also talked with Dan Flanagan, executive director of Friends of the Urban Forest, who has been advocating for a dedicated, long-term tree maintenance funding program.

“We don’t want a short-term solution," Flanagan said. "Trees require care over a long time. It would be wrong for the supervisors to see the light of day and give money for two years, then cut it” – like what has happened in past years.

The catch with parcel taxes and set-asides is that they require two-thirds of voters to approve such a ballot measure. In polling done a couple of years ago, urban forest advocates received around 60% approval for these options – not quite enough to attempt a ballot measure.

But with the increasing tree problems, the fund's supporters feel they are getting the wind at their backs. Wiener sees a ballot measure coming in November of 2016, once the working group has reached a finalized funding proposal.

In The Meantime...

While the DPW continues transferring tree care to property owners, it recently made a stopgap effort to help prevent some of the most dangerous situations from getting worse. In late November, it eased the permitting requirements needed to remove the dreaded ficus (although you’ll still have to pay the $339 removal fee).

Fallen tree on Divisadero, December 30, 2014. Photo by Cara K. / Hoodline.

Fallen tree on Divisadero, December 30, 2014. Photo by Cara K. / Hoodline.

For now, if you or your property do get damaged from trees, you can try filing a complaint with the city attorney, or filing for damages with the Department of Recreation and Parks (if the damage occurred on its property).

If you're a property owner wondering if you're responsible for the tree on your sidewalk, check out this handy map provided by the DPW to be sure.

If you're ready to brave getting a new tree, the Friends of the Urban Forest will help you select a tree variety (for a discounted price) that's right for your property and location.

Finally, you can offer feedback to the Urban Forest Plan working group, and/or make a donation to nonprofits working on this problem (like the Friends of the Urban Forest).

And, if you care about the issue, make sure to vote in 2016.

Max Cherney contributed to this article.