This is the second in a series of history posts from local historian, author and professor Art Peterson, who's given Hoodline permission to reprint some of his writing about North Beach and nearby neighborhoods. They appear in his local history book Why Is That Bridge Orange? and other previously published works.

On November 27, 1999, the day Finocchio's nightclub was to close at 506 Broadway, owner Eve Finocchio answered the phone as she had for many years: "Forget your troubles and woes and join us at Finocchio's, family-owned since 1936."

As the premier female impressionist club this side of New York City, Finocchio's, "where all the most beautiful women are men," did, indeed, have a long run, entertaining an estimated 300,000 patrons over its 63 years of existence.

Eve, who was in her eighties by 1999, had run the club on her own since her husband Joe died in 1986, but she eventually decided to hang it up. Business was down ("People seem content to rent a movie and stay home"), and her rent was being increased from $4,000 to $6,000 a month. And in modern San Francisco, a man dressed as a woman was nothing exotic.

Photo: Geri Koeppel/Hoodline

Thus, a venerable tradition came to an end—one that predates the Broadway club. The original Finocchio's opened as a speakeasy at 408 Stockton St. in 1929, and unlike its later days, there were no Gray Line buses lining up at this sanctuary for "bohemians and artists."

One of the club's early denizens was Henry Hay, a founder of the Mattichine Society, a pioneering gay rights organization before the words "gay" or even "homosexual" existed.

In an oral history collected by Chris Carlssen, Hay described the club protocol: "A waiter might approach you with a bottle of wine and a card sent over by a young man. If you weren't interested, you turned over your glass and that would be it. If you were interested, the waiter would fill your glass and bring another. Then the young man would come over and the waiter would introduce him."

Photo: Courtesy of SF Public Library Historical Photo Collection

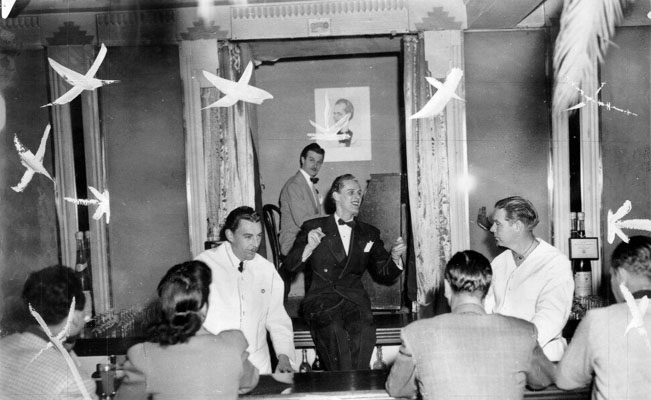

Female impersonators were part of this scene, particularly one performer who drew enthusiastic crowds with an imitation of the legendary Sophie Tucker. The Finocchios, Joe and his wife Marjorie (who, as "Madam Finocchio," was the prime mover behind the club), eventually moved the club to Broadway, but with a difference: the prime audience for the new club would be heterosexual.

They hired men—mostly gay, but some straight and married—who knew how to dress as women, nudged along by a bountiful collection of wigs, feathers and lashes. The cast, usually numbering 16, was fascinatingly authentic. "I wish I had legs like that," the females in the audience would regularly enthuse. And for those patrons who needed additional convincing, the emcee had some advice: "The more you drink, the better we look," he would say.

But being able to turn oneself out as a beauty was only one of the requirements. Most performers had to be able to sing like Judy Garland or Barbra Streisand or some other established diva—no pantomimes were allowed, a demand that eliminated many a beauteous baritone.

Further, the Finocchios ran a tight ship: performers were expected to dress as men as they arrived and left the club. "We were illusionists, not transvestites," said one of the show's stars, David de Alba.

Joe Finocchio would claim he had the "cleanest show on Broadway," but in the early days, the police were not convinced. The exotic club had its share of raids.

One bust came for selling liquor after 2am, but a Chronicle reporter noted the arrest came at 1:45am. Joe did everything he could to avoid trouble."They told me that if I run the place straight, everything would be fine. They don't want the entertainers to mingle around the customers. I promised to run it like a regular theater."

There was another dustup in 1943, when the club was found to be selling booze to military personnel "outside of authorized hours." After that, Joe agreed to limit drinking hours for the military to between 5pm and 10pm.

Photo: Courtesy of SF Public Library Historical Photo Collection

Of course, even with all the policing and self-policing, boys will be boys. "Stage-door Johnnies" were never in short supply, and there were stories of after-hours carryings-on with celebrities like Errol Flynn and David Niven. When Howard Hughes saw the show with his then-girlfriend Ava Gardner, he returned to the club and whisked away one of the performers for what turned out to be an extended relationship.

In general, though, the goings-on were squeaky clean. One young man, arriving from the Midwest to seek out his sexual identity, was disappointed when, arriving at the famous club, he was confronted by "men streaming in and out of the entrance, appearing overwhelmingly guy-like. They belched and patted their bloated bellies and spat more than seemed possible."

In its later years, Finocchio's had a not-altogether-deserved reputation as a tourist trap. The cast put on four shows, six nights a week; for a $3.50 admission in the 1970s, one could stay all evening. There was no drink minimum, a highball was $1.25, and an additional 25 cents would get you a mai tai.

But what truly brought people to the club was the quality of the entertainers. There was the elegant MC Carroll Wallace, who opened the show with the line, "In New York, Mr. Ziegfeld glorified the American girl ... Here at Finocchio's, we glorify the American boy." He would then launch into his trademark song, "I'm a singer but I haven't gotta voice," and other standard patter like, "If you want to take pictures of the performers, please give them time to pose."

Lucina Phelps, the Sophie Tucker expert, was straight and married with children, and starred at the club for 27 years. Lavern Cumming, a dazzling beauty and another longtime performer, was able to startle his audience by taking his high falsetto voice to a deep baritone.

Not every performer fit the mold of a standard beauty. Russell Reed, for instance, weighed in at 300 pounds, billing himself as the "ton of fun." He was a master of facial inflections and gestures, and a hilarious striptease that took him down to his red pajamas was an audience favorite.

Then there was Elton Paris, who would wander on stage with a deadpan expression, wearing dowdy women's street clothes and tennis shoes, making people laugh before he said a word. Like Lavern Cummings, he could drop his falsetto voice down into the baritone range, as he demonstrated on the song "Spinning Wheel" ("What goes up must come down").

Perhaps the most successful of the performers was the 6-foot, 6-inch comedian Lori Shannon, who went on to a supporting role as Archie Bunker's drag-queen friend in All in the Family.

Photo: Courtesy of SF Public Library Historical Photo Collection

Over the years, the Finocchio family remained very much in charge. Night after night, Joe would escort guests to their seats; the Finocchio children, and later the grandchildren, served drinks. The family did have its ups and downs. When Joe divorced Marjorie and married Eve, Marjorie retained partial ownership of the club, and she would not allow Eve through the door. But when Marjorie died, Eve took charge. After that, it was said that a sure way to get fired from the club was to launch into the old song "Margie."

By 1999, Tallulah Bankhead, Frank Sinatra, Bob Hope and the other glitterati who'd once inhabited the club were gone. Even the tour buses came only occasionally.

Eve planned no special ceremony for the closing; the regulars did their usual Whitney Huston and Madonna bits. But when Laurence Ferlinghetti got the word that Finocchio's was no more, he spoke for all of North Beach. "What a drag," he said.