[This article is part of a series of excerpts, edited by Marjorie Beggs, from the Neighborhood Oral History Project interviews conducted in 1977- 78 under a federal CETA contract by Study Center, the publisher of Central City Extra. The nonprofit has a large original collection of additional oral histories and photos in print form, and they (and Hoodline) are looking for people to help digitize and publish stories from the collection. If interested, please contact editor (at) hoodline (dot) com.]

Dr. Kazue Togasaki lived an amazingly rich life, stretching from her childhood experience of the 1906 earthquake and fire to her long professional career as an obstetrician: She was one of the first two Japanese American women to get a medical degree in the United States. She delivered babies and had other medical responsibilities at Tanforan assembly center and Tule Lake, Poston, Manzanar and Topaz relocation camps where she was held during World War II.

The biographical dictionary Notable American Women says that Dr. Togasaki, who had an active practice in San Francisco until she retired at 75, delivered more than 10,000 babies in her long career. One of nine siblings, she and her five sisters all became nurses or doctors and none married.

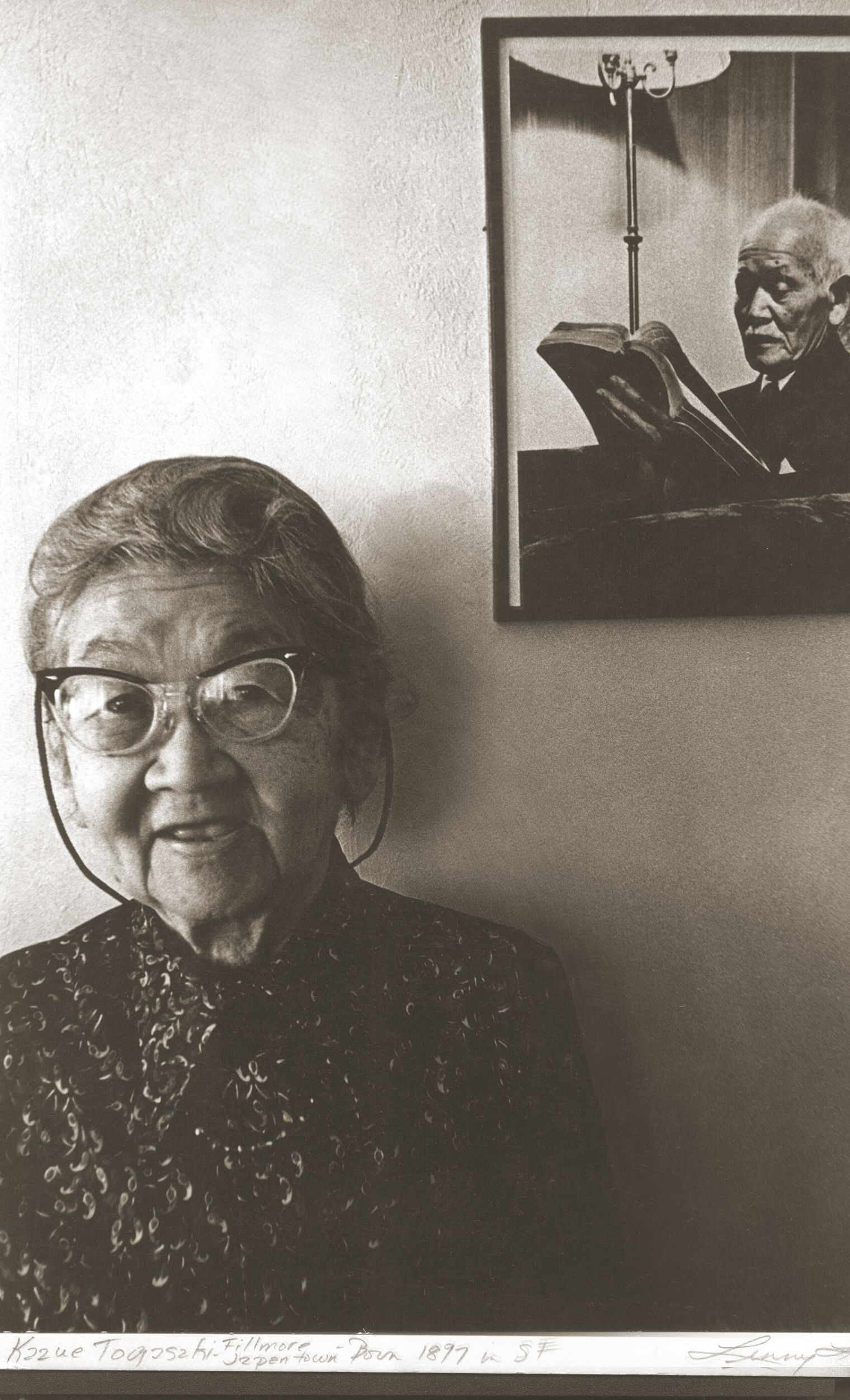

Dr. Togasaki was 81 when Study Center’s Oral History Project staffer Lenny Limjoco interviewed and photographed her in 1978 as a notable resident of the Fillmore/Japantown neighborhood, though she had lived in the Mission, SoMa and Tenderloin as a child. She died in 1992.

— Marjorie Beggs with Central City Extra, April 2013

Lenny Limjoco: You lived at Geary and Mason when the 1906 quake hit. What happened to you and your family?

Dr. Kazue Togasaki: I was 9 years old and was going to school at Clement Grammar on Jones and Geary. [The quake and fire destroyed the school.] I remember waking up that day — our bedroom was next to the kitchen — and the chimney had fallen in, and the kitchen was filled with soot. I remember we got dressed and walked from our house to 14th and Church where there was a hill, and that afternoon and for two days in the daytime we sat, watching the city burn. We were staying with my uncle on Dolores where it comes into Market Street. He had a carnation nursery near Church and Market. When the fires started, my younger brother, who was about 6 years old, would go stand at the window, see the whole city burning, and then scream. We tried to keep him back from the window, you know, but it just fascinated him — he kept going to the window and screaming.

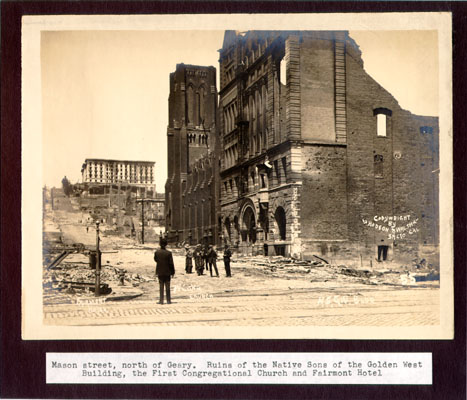

Mason north of Geary, via Central City Extra, from the History Center's photograph collection at the San Francisco Public Library.

Mason north of Geary, via Central City Extra, from the History Center's photograph collection at the San Francisco Public Library.

What was your early family life like?

I was born in 1897 and my family lived in the Inner Mission, I think on 10th Street. When I was 3 years old, we went back to Japan, then came back to San Francisco, and a year later, my second brother was born. For a while we lived on Stevenson Street between Sixth and Fifth, then moved to Geary and Mason, a block from the St. Francis Hotel. My parents had a little store at 405 Geary that sold Japanese tea and rice and chinaware.

They opened it to make a living. By the early ’40s, the store was one of the biggest Japanese wholesalers in the city.

My father had come to San Francisco in 1886 to study American law, right after he graduated from law school in Japan, but he couldn’t find work here so he went back to Japan. No work there, so he came back here again, and that’s when he met my mother, who was a student. Later, they went back to Japan and got married, but still there was no work so they came back here. My mother was the daughter of a merchant so she knew how to buy and sell, but my father, a lawyer, not a businessman, thought it was wrong to make a profit selling. So she taught him.

After the earthquake, we lived at Post and Buchanan and I went to school at Hearst Grammar, and then, a year later, the Gentlemen’s Agreement came in. [An informal agreement between Japan, the US government, and San Francisco city leaders, in which the city ended school segregation in exchange for Japan curtailing emigration to the US. Thanks to Hana M. for clarifying.]

My brothers and I and one other girl were the only Japanese at Hearst, and we were told we couldn’t stay and had to go to the Japanese school, over on Sutter between Buchanan and Laguna. I think we were out of school entirely for a semester, but in that time, the Japanese government intervened and made such a fuss, we all had to go back to Hearst again.

Kazue Togasaki at the Woman’s College of Pennsylvania, January 1, 1933. Photographer unknown. Via Drexel University College of Medicine, Archives & Special Collections: Women Physicians, 1850s-1970s.

Kazue Togasaki at the Woman’s College of Pennsylvania, January 1, 1933. Photographer unknown. Via Drexel University College of Medicine, Archives & Special Collections: Women Physicians, 1850s-1970s.

For high school I went to Lowell — it was on Hayes and Masonic then — and after that to U.C. Berkeley for two semesters. Then I went to Stanford University and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in zoology in 1920.

Did you go to work after that?

At that time, there was nothing for a Japanese girl to do, except maybe be a salesgirl, and my father wouldn’t let me do that, so I got a job as a maid working in a family for about a year — it was crazy and it was no fun, so I went into nursing, a two-year program at Children’s Hospital that I completed at the top of the class. They had accepted me in the program, but I still couldn’t work here — the climate in San Francisco was that they just “didn’t use” Japanese nurses; the staff wouldn’t have it. Then I went to work as a secretary for the YMCA International Institute. They wanted me to also do fundraising, but my father said, “No daughter of mine is going to be a beggar.” So I lost that job. Next, I took one year in public health nursing at U.C., and I might have gotten a job in Stockton, which had a big Japanese population, but I decided I was getting sick and tired of breaking my back to work and then having the job go to the white nurse. It just wasn’t worth it.

In 1929, I went back East to Women’s Medical College in Philadelphia and became a doctor, a general practitioner, graduating in ’33. I did my internship back here at Children’s Hospital, then had a practice with a Caucasian doctor in an office downtown, on Sutter and Powell, until the early ’40s. I bought this house at Buchanan and Post, the center of the Japan community, in 1938.

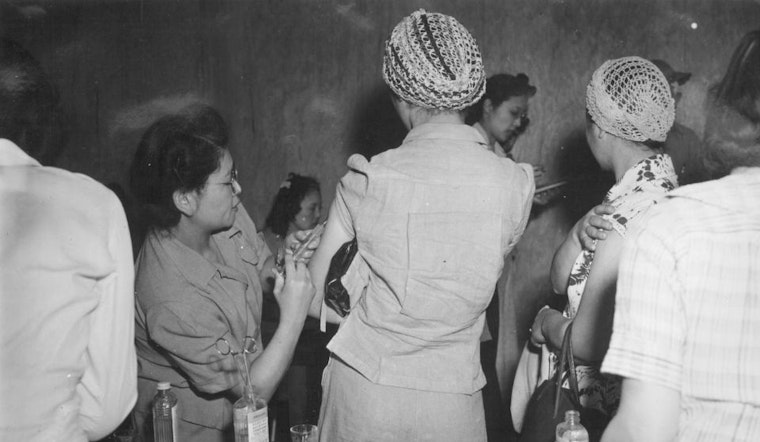

"Newcomers waiting their turn to be vaccinated at this War Relocation Authority center for evacuees of Japanese ancestry." Dr. Togasaki appears to be in the foreground. Photograph by Clem Albers. Manzanar, California. April 2, 1942. Courtesy of UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library.

"Newcomers waiting their turn to be vaccinated at this War Relocation Authority center for evacuees of Japanese ancestry." Dr. Togasaki appears to be in the foreground. Photograph by Clem Albers. Manzanar, California. April 2, 1942. Courtesy of UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library.

What happened during World War II? Were you still a general practitioner?

Yes, I was, and an obstetrician. Because I was one of the older Nisei sent to the Tanforan assembly center, I was asked to help open up the medical services there. [Tanforan was one of 18 first stops for detainees on the West Coast and Arizona. From there, they were sent to relocation centers.] The relocation was war hysteria. They just told us, on such and such a day be ready to leave. They had big buses and you were allowed to take two suitcases, whatever you could carry. I just remember being busy all the time at Tanforan. I stayed there a month, responsible for setting up the hospital, trying to get everything organized. I had the head nurse and the instructor of nurses at Stanford University Hospital and a doctor, all Japanese, working with me at Tanforan. They learned a lot from me because I was the top dog — 10 or 15 years older than them with real work experience. In that month, I delivered 50 babies in the camp. Sometimes I stood behind the doctor and taught him how to deliver. I thought it was my duty. In other camps, I know they’d send the pregnant women out to the nearest county hospital to deliver, but I never thought about sending them out from Tanforan. From Tanforan I was sent to the Stockton assembly center, then to the Tule Lake, Poston, Manzanar and Topaz relocation centers. I stayed at Topaz [in Utah] and got out, I think, late fall of 1943, something like that.

What happened to your house when you were in the camps?

I had a friend who was supposed to take care of it, but she was dumb as a doornail and she rented it to a bunch of . . . well, everything was stolen. By the time I got back a year or two after the war, there wasn’t much left, all my good things were gone. And I think that happened to most of the Japanese. I did get my house back, but it was one grand mess, so I just started over again. I set up practice here in this neighborhood, and everybody was happy to see a Japanese woman doctor. In all the years before I retired, there was only one other Japanese woman doctor in this area, but she got married after a year and left.

Dr. Togasaki during this 1978 Study Center interview. Photo by Lenny Limjoco/Central City Extra.

Dr. Togasaki during this 1978 Study Center interview. Photo by Lenny Limjoco/Central City Extra.

What about the neighborhood now and the Japan Center [built in 1968]? Do you like it?

I don’t like it. So many of the Victorians were torn down for it. I think it’s a steal because the area should have remained for the average Japanese family. They had to move out — scattered out to the Sunset — and their businesses closed. They lost every way. The builders destroyed the neighborhood. Maybe as time goes on things will change and people will be able to come back, shop in a Japanese store, the way it was before. Me, I’m perfectly happy to stay here. I grew up on Post and Buchanan. What was there is all gone now, but, you see, it’s still near where I grew up.

This is another in a series of photos and excerpts, edited by Marjorie Beggs, from the Neighborhood Oral History Project interviews that the Study Center conducted in 1977-78 under a CETA contract.