Today's story is the first in a three-part series on Coit Tower, running today through Wednesday. In subsequent articles, we'll explore how the tower's maintenance is funded, and look at proposed changes in the tower's offerings—including the possibility of food and online ticketing.

For decades, the entire second floor of the iconic Coit Tower—the white column that’s been a beacon atop Telegraph Hill since it was completed in 1933—went unseen by the public. While many visitors have seen the famed Depression-era murals on the first floor, or decades, the delicate secco frescos on the second floor of the building has been closed off—until now.

In 2014, the San Francisco Recreation and Park Department and the San Francisco Arts Commission, which maintain and operate the tower, decided to embark upon the first major tower restoration since 1990. To help restore the murals, they teamed up with Anne Rosenthal Fine Arts and ARG Conservation Services.

Library by Bernard B. Zakheim.

Both the frescos and the murals were painted by Depression-era artists, and have been subject to a lot of vandalism over the years, a particular problem in the disrespectful mid-20th century. Other issues have included leakage from the roof (an issue ever since the Tower was built), scratches and abrasions from visitors' backpacks and purses, flaking paint and damage from the salt air. Some restorations had already been done over the years, but that only ended up complicating the process.

“The biggest challenge [in restoring the murals] ended up being [that] the walls have been treated numerous times [in the past],” said ARG project manager Jennifer Correia. “Anne [Rosenthal] was familiar with where previous treatments were located. The question was whether to remove those treatments. What treatments didn’t work, and what did work?"

"Sometimes there was acrylic overpainting. They were vandalized, so one choice was to take out graffiti and inpaint," she continued. "But sometimes you’d see graffiti popping through. Graffiti [can be] very difficult. You can’t always take it off. Sometimes a ghost remains, and you’ll never be rid of it.”

City Life by Victor Arnautoff.

With effort, the teams were able to remove the graffiti, and the entire tower restoration project was deemed such a success that it recently received a Governor’s Historic Preservation Award (one of 11 such awards for 2015) from the State Office of Historic Preservation (OHP) and California State Parks. The award acknowledges the four-way collaboration among the two city agencies, ARG and Anne Rosenthal.

“The jury was impressed with the degree of care that went into repairing the building’s structure while maintaining original, historic features, and protecting the Tower’s murals throughout the process,” State Historic Preservation Officer Julianne Polanco told Hoodline via email. “Equally impressive was the excellent work to clean and conserve the murals and find solutions that would protect the artwork, yet ensure it remained accessible to the public.” She also noted the dedication of staff, volunteers and community members. (For a look at the damaged murals pre-renovation, visit Protect Coit Tower's website page with photos.)

Department Store by Frede Vidar.

There are 27 total murals and frescoes in Coit Tower. Those on the main floor were painted in oil on canvas adhering to the wall, while the more fragile works on the second floor are secco frescoes, in which paint is applied directly to moistened plaster.

Coit Tower itself was not designed for murals, but rather as a monument. But in 1934, the Public Works of Art Project (a precursor to the WPA) hired a group of activist artists, many of them students or apprentices of muralist Diego Rivera, to portray Depression-era California on its walls.

For the most recent restoration, four specialists spent about a month working on the second floor alone. Since relatively few secco frescoes exist, only a small number of restoration artists are specifically trained in dealing with them, which meant specialists had to be called in. Adding to the challenge was that, unlike on the ground floor, the walls of the second floor had not been extensively treated in prior years. After careful dry cleaning, areas of deteriorating plaster were stabilized with poultices and consolidants.

Finally, the painting could begin—inpainting, that is, not overpainting. The focus is on filling in the areas of loss, matching the original artist’s brush strokes; overpainting would be visually confusing, explained Correia.

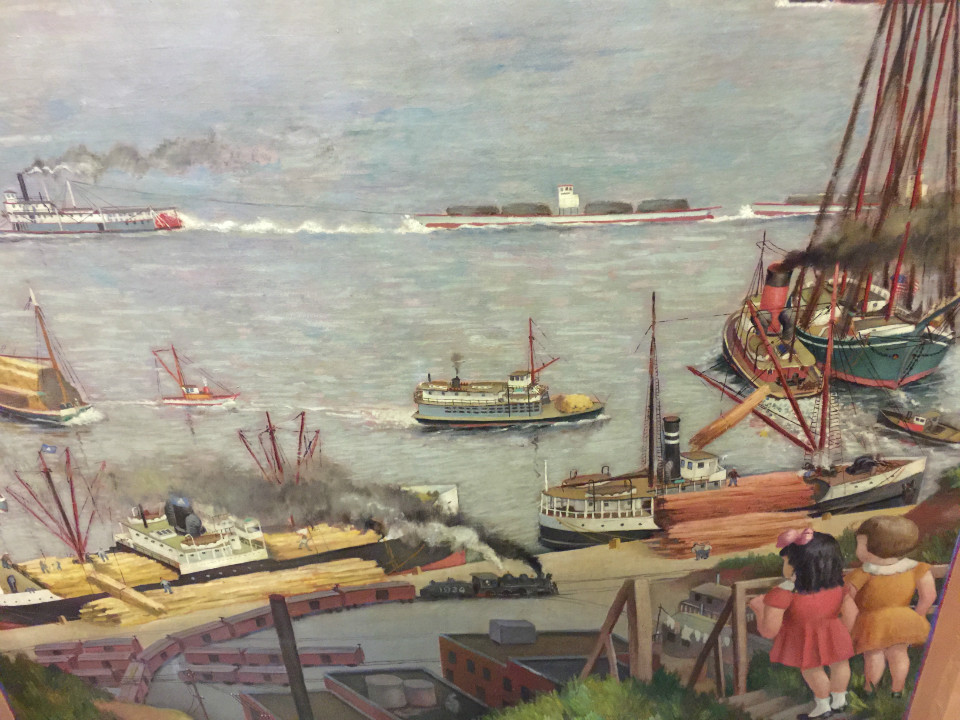

Industries of California by Ralph Stackpole.

The downstairs murals, which depict banking, farmworkers, agriculture, business and infrastructure, are often very solemn, befitting the hard times during which they were conceived. The upstairs frescos are lighter in tone, representing camping, home life, sports and leisure.

To reach the second floor, a few people at a time are allowed to walk up a narrow, twisty staircase from the elevator lobby. The staircase wall itself boasts a huge, swirling mural by Lucien Labaudt. It’s a magnificent mass of little vignettes, including a little self-portrait of the artist and a glimpse of Eleanor Roosevelt studying a map. Custom platforms and ladders had to be constructed to restore it.

Unlike the circular panorama of murals on the ground floor, the second floor is divided into three small rooms. The images depicted include a college football player, horseback riders and golfers, children in a playground, and scenes of the pastoral outdoors and hunting.

Jane Berlandina's Home Life. (Photo: Sandra Cohen-Rose/Flickr)

Particularly surprising is Jane Berlandina’s “Home Life," which, unlike the other frescoes, was painted on a dry surface with egg tempera, and had never been previously conserved. It’s markedly different in style from the other artworks in the Tower, because it doesn’t follow the colorful, social realist style that we associate with the Depression.

Berlandina’s scenes of a middle-class family—dancing, baking a pie, playing bridge, playing piano—are rendered in muted shades of brown, red, white and green, and consist of airy outlines rather than the clear details scene in the paintings of the other muralists. The resulting work projects a light spirit, in contrast to the solid frescos and oils, with their more serious subjects.

Otis Oldfield's mural, depicting his daughters Jayne (left) and Rhoda.

Although protecting the murals and frescoes will be an eternal challenge for Coit Tower's caretakers, the conservators expect this recent upgrade to last longer than any of the previous ones.

“It was wonderful to see the complete restoration,” said Jayne Oldfield Blatchly, who appears as a little girl in one of the ground-floor murals painted by her father, artist Otis Oldfield. She told us how sad she’d been to watch the artwork deteriorate over the years. “I suppose we’ll have to trust that future people in charge will continue the everyday practice of making sure they don’t get [neglected], as happened in the past.” The recent award, she said, is well-deserved.

Coit Tower is open daily from 10am-6pm; admission is free, though there is a charge for elevator rides based on age (SF residents get $2 off). To see the stairwell and second-floor murals, you must schedule a docent tour at coittowertours.com.