“That doorbell rings, and my heart just jumps! I think, ‘Oh, Jesus! Who’s coming through the door?’” said Mark Norman.

Norman, who is retired from a career working for the IRS, has been living in the same apartment in Alamo Square for roughly 25 years. After his wife passed and he developed emphysema and other health conditions, he said walking became “iffy”; he became apartment-bound, ordering in food instead of leaving to run errands. Meanwhile, stuff began piling up in the apartment. “I have bags of trash because I couldn’t get down the stairs,” he said; they filled up in his back hallway until he could no longer use it.

It was a problem that he kept private. “I don’t answer the doorbell unless I’m expecting someone,” said Norman. “I feel like Anne Frank in here. Inside, just hiding in the cellar.” But when his building changed property management companies and his apartment was inspected, his cover was blown. He received a notice that he had to clean, and hired Collectors Care, a cleaning and organization service with a speciality in helping clients with hoarding disorders. After two days, over a hundred garbage bags, and $2,600, Norman hoped to be free from the issue. However, some clutter remained, and the cleaning had revealed floor damage. “A couple of days later, that’s when I got the eviction notice."

Tipster John D. alerted us to the situation. If you talk to mental health professionals, landlords, and eviction attorneys, it soon becomes clear that Norman’s case is far from unusual. In the words of John Franklin, a program manager at the Mental Health Association of San Francisco (MHA), “That’s just the tip of the iceberg.”

Though the issue can seem invisible in San Francisco—you probably haven’t seen it in the news since the voyeuristic hubbub surrounding the “Hoarder Mummy House”—it occurs with surprising frequency and has a high cost to the city: it leads to evictions and homelessness, increased risk in the case of fires, health concerns, depression, strained friendships and families, and over $6 million a year from taxpayers, landlords, and social services.

Daniel Bornstein, a real estate attorney who has run bootcamps for landlords and co-founder of the property management group trying to evict Norman, said that on average in his practice, he encounters a hoarding eviction case a month. Erin Katayama, an attorney for the Homeless Advocacy Project said that last year, her office worked on approximately 26 cases that involved allegations of hoarding and cluttering. Over a quarter of the cases were eventually evicted, although some for reasons other than hoarding.

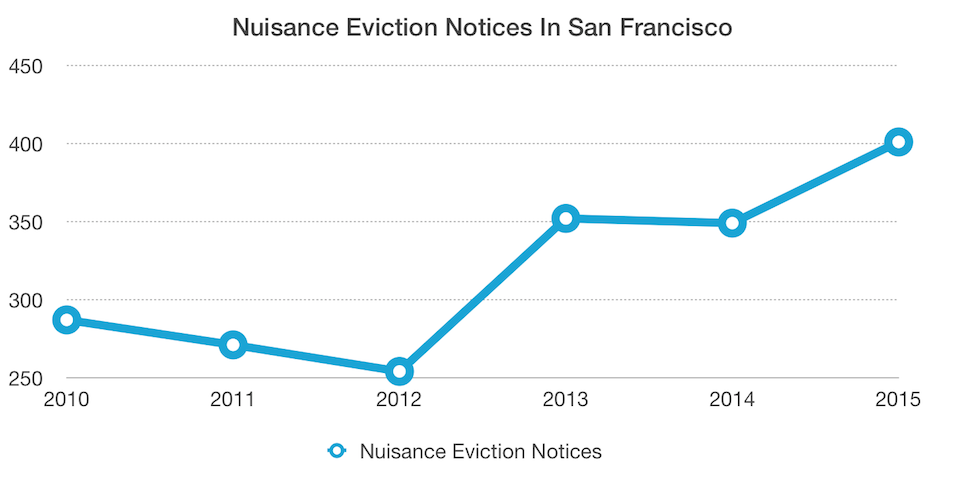

The number of nuisance eviction notices, a category that includes more than hoarding-related issues

In 2009, San Francisco published a report on its task force for hoarding and cluttering. At the time, report estimated that the disorder impacted 1-2 percent of the population and made recommendations of how to implement more effective treatment. Since then, Franklin says all of the recommendations have been put into action, and the findings are that the problem is much more prevalent than had been thought.

“I think everybody now realizes how grossly the number of people with collecting challenges has been underestimated,” said Franklin—his program now works with four times as many clients as it had previously. Now it appears that hoarding and cluttering disorder impacts more than twice as many people as the task force had originally thought, 2-5 percent, or 20,000 to 40,000 San Franciscans. That means there are twice as many people who suffer from cluttering as people who have Alzheimer’s.

Franklin says that, based on what he’s seen at international hoarding and cluttering conferences he attends every year, the disorder seems to occur at the same rate around the world, but San Francisco’s exorbitant housing market poses special problems.

First of all, smaller apartments and SROs mean that health and safety concerns arise more quickly. “If you were in a rural area or had a three-car garage or a basement, this could take a lot longer to come to people’s attention,” explained Franklin.

Secondly, it usually takes years for the amount of stuff to become an issue, which means that many people who face eviction for hoarding live in rent-controlled apartments. If they are evicted, the high cost of renting leaves some homeless.

Norman, who has lived in his apartment for over two decades, uses his pension and Social Security to pay over $900 a month for his one-bedroom apartment, a quarter of the current market price. “My rent probably was the lowest of the building, even though it wasn’t that low,” he said. He is working with Adult Protective Services and a lawyer from Legal Assistance to the Elderly to find a settlement that will allow him to keep his apartment. As for what he’ll do if he is eventually evicted, he said, “I’ll jump off that bridge when I come to it. I have no idea what I’ll do.”

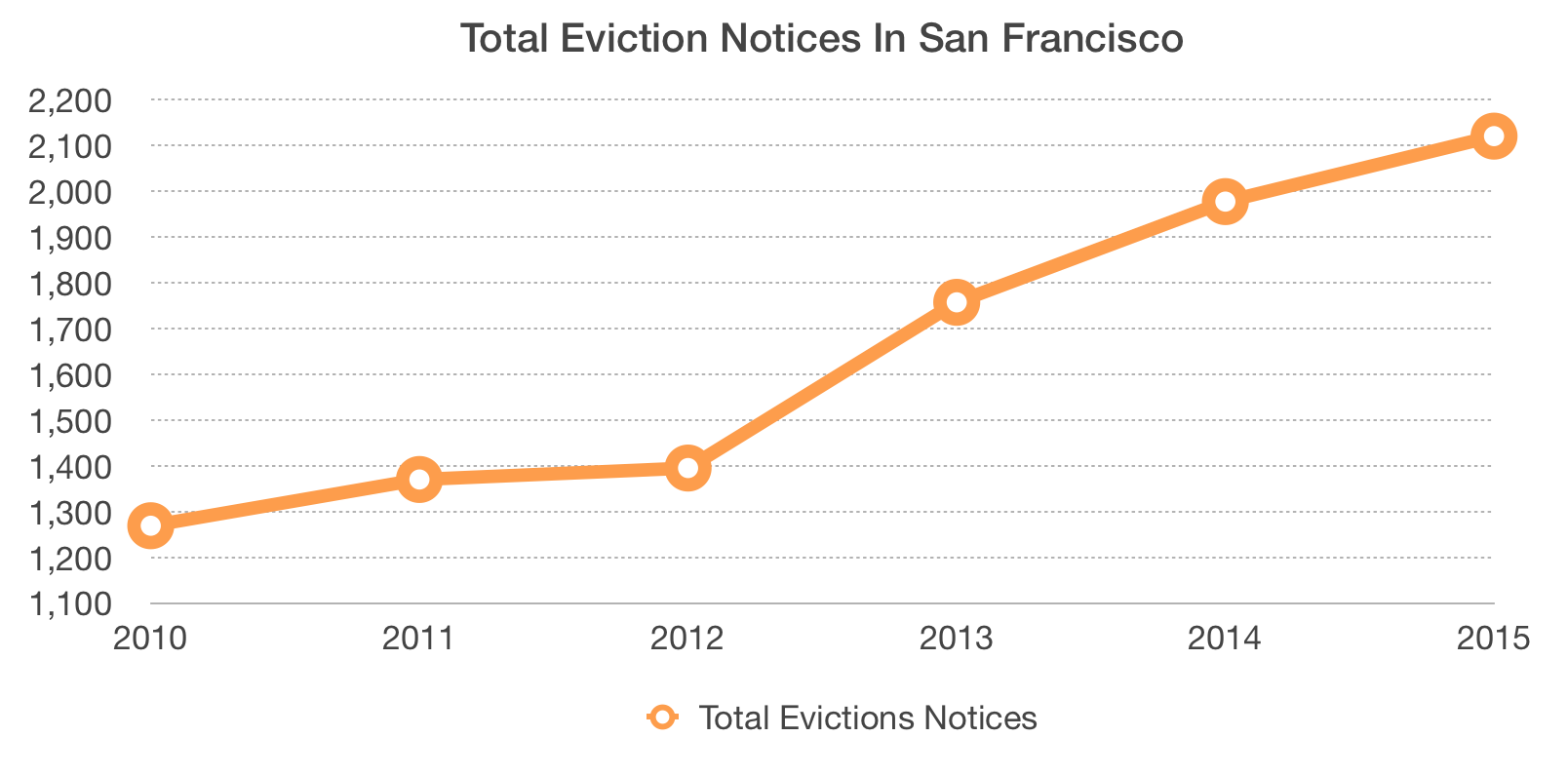

Finally, the number of evictions are rising in San Francisco as a whole. The city usually lumps hoarding evictions under the broader category of nuisance evictions, so there are not specific statistics. Katayama said that her personal perception is that she’s seen more cases come through in the last three years, but notes that it may simply be that more people have heard about their services—another sign of the increasing awareness surrounding the disorder.

Data from the Rent Board

There are other economic dynamics at play with hoarding and cluttering. For example, hoarding expert Randy Frost considers William Randolph Hearst a hoarder, but Hearst’s immense wealth meant he could store his ever-expanding accumulation of collectables, art, and antiques—he eventually reached the point where he sent items he bought directly into warehouses where he never saw them again.

People with the means can store their goods, pay to have someone to help clean them out, or even buy a new house. Sandra Stark, who once struggled with the condition and now facilitates a peer-led hoarding response team with the MHA, said “I had one client who fortunately had some resources and was able to pay—like $3000 or so—for help with cleaning out … The cleaners weren’t to throw anything out. It was all going into storage. She has five or six units, and she never goes back again to the storage. I told her, ‘You’re paying for a whole other apartment.’”

The language used to describe hoarding and cluttering behaviors, including being “outted” or “coming out,” parallels that used in the LGBT community. Stark, who loved entertaining and having people over until her possessions took over the house, remembers the day she was outted to her daughters. Someone had told them, and they showed up to do a clean out—a tactic that almost always fails because it doesn’t address the underlying problem. Stark agreed because they were her daughters. “I thought they knew what I loved and they would save more of my stuff,” she said. “But they didn’t … It was devastating.”

Afterward, she described her angry phone conversations with her daughters—it took nearly a year for her to stop bringing up things that were missing. After paying for the cleaning, she had to pay to replace things like her silverware, which had been thrown out. Then, in a year and a half, the clutter was back worse than ever.

Her journey toward regaining her life didn’t start until she saw psychologist Michael Tompkins discussing the condition on Oprah. “I thought, ‘Oh my God. That’s me. He’s talking about me, and there’s a name for it. And I’m not alone; there are other people. And I’m not this horrible, dirty, lazy person. I have a problem.’ It was just amazing.”

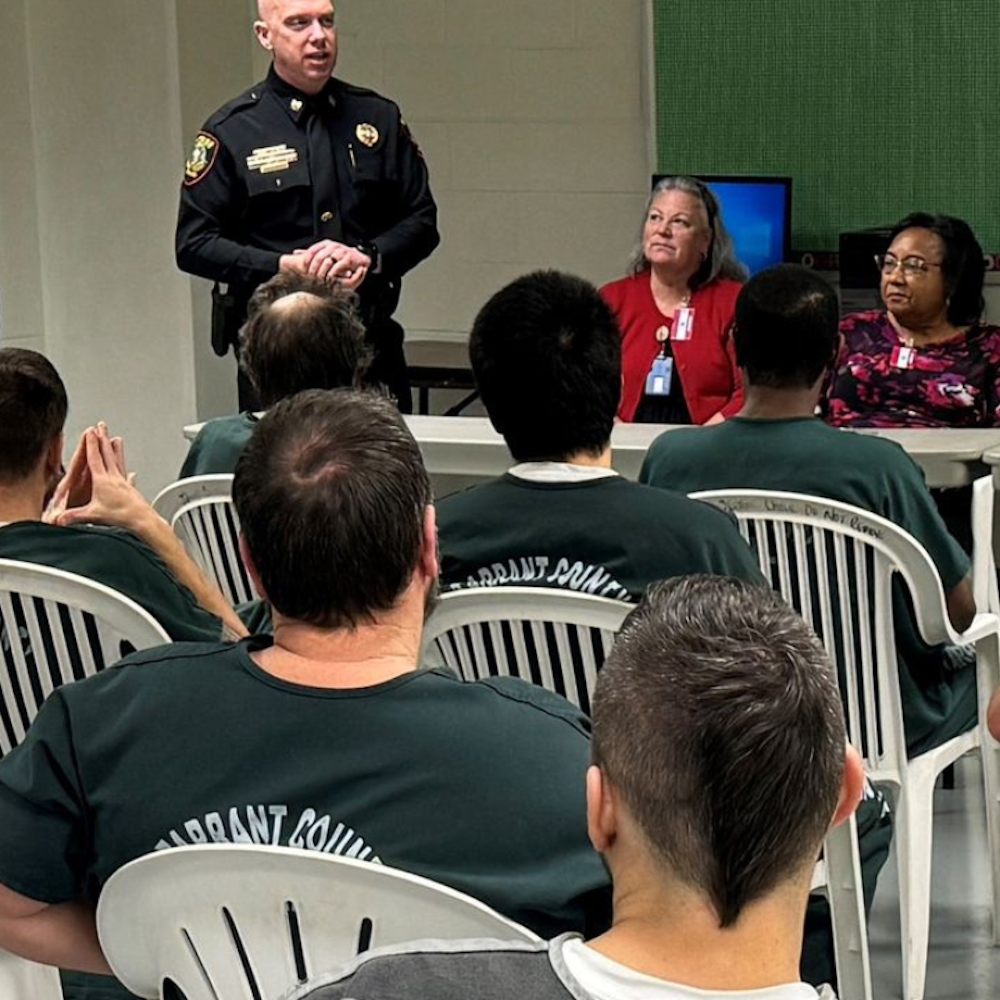

Sandra Stark facilitates a peer-led hoarding response team with the MHA

She went online to look up resources and eventually found herself at a support group with the MHA. She became friends with one of the participants, who offered to be her clutter buddy. “I think success almost depends on having someone who can help you, even if they just come and keep you company while you’re decluttering.” She said her clutter buddy likes to remind her that it took Stark three years to accept her offer to come to her house. “And even then, I cried as she crossed the threshold. It’s just—it’s so shameful. And so humiliating. Which is why everyone’s in the closet about it.”

Now Stark works full time at the MHA, offering others the type of help she found there. The peer- and therapist-led sessions are free—as are the resources provided by Adult Protective Services, Legal Assistance to the Elderly, and the Homeless Advocacy Project.

Stark’s experiences highlight the issues surrounding hoarding and cluttering. It’s not an accident that the disorder is discussed less frequently than Alzheimer’s. Secrecy compounded by stigma and a lack of awareness can prevent people from coming out about their conditions or seeking out treatment. "The general profile [of people who suffer from cluttering problems] is artistic, eclectic, articulate, creative, and responsible," said Franklin—but that's not how it is perceived.

Then, by its nature, the disorder can take time to treat, but as Bornstein explained, “Oftentimes, the city and the support services don’t get involved until there’s a crisis,” and the clock is running as soon as an eviction notice is served. (A three-day notice can be extended to several months because hoarding is considered a disability, but time is still tight—for comparison, the MHA’s peer- and therapist-led sessions are 20 weeks long.)

Bornstein, who both co-founded the group managing Norman’s apartment and legally represents it, said, “It’s a tricky thing because we have to balance the rights of the individual who is in the unit versus the need of the community. And cluttering and hoarding is a sort of litmus test as to which rights are more persuasive.”

Norman, for whom the results of the litmus test will be very real, concluded, “I really don’t know what to tell you except it’s horrible to be in this situation. If you can ever own property, own it.”