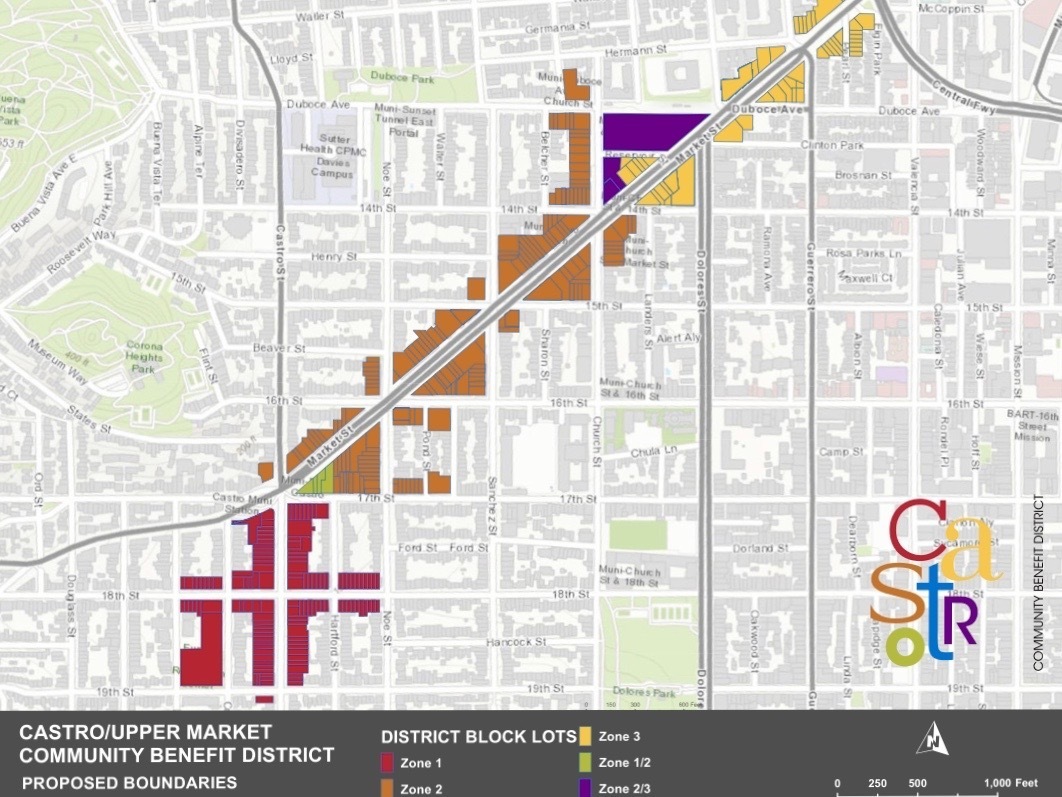

The Castro/Upper Market Community Benefit District (Castro CBD) is considering installing a network of security cameras in the Castro, Duboce Triangle, and Upper Market area.

The purchase and installation of the high-definition cameras would be funded by tech entrepreneur Chris Larsen, the co-founder of cryptocurrency company Ripple and mortgage lender E-Loans. He would also finance the cameras' first year of maintenance.

Larsen, who lives in Russian Hill, has been gifting security cameras to the city's CBDs since 2012, and his network now spans 1,000 cameras. He was driven to pitch in after his father-in-law's car was robbed, his own car windows were smashed, and his house was targeted for a burglary attempt.

“[Criminals] don’t care at all — they don’t care if they’re being seen,” Larsen told the New York Times in a July interview. "It’s brazen."

Larsen's camera network is currently spread across five CBDs in the city: Fisherman's Wharf, Japantown, Mid-Market, the Tenderloin and Union Square. If it approves the cameras, the Castro CBD would be the sixth member of the group — and the Lower Polk CBD has a similar network utilizing the same vendor.*

"I understand why the Castro CBD wants to do it," said District 8 Supervisor Rafael Mandelman. He and Andrea Aiello, the Castro CBD's director, say they hear constantly from constituents about property crimes in the neighborhood.

The petty crimes that plague the Castro — smashed windows, small fires, car break-ins, bike theft, phone theft and residential burglaries — have skyrocketed this year.

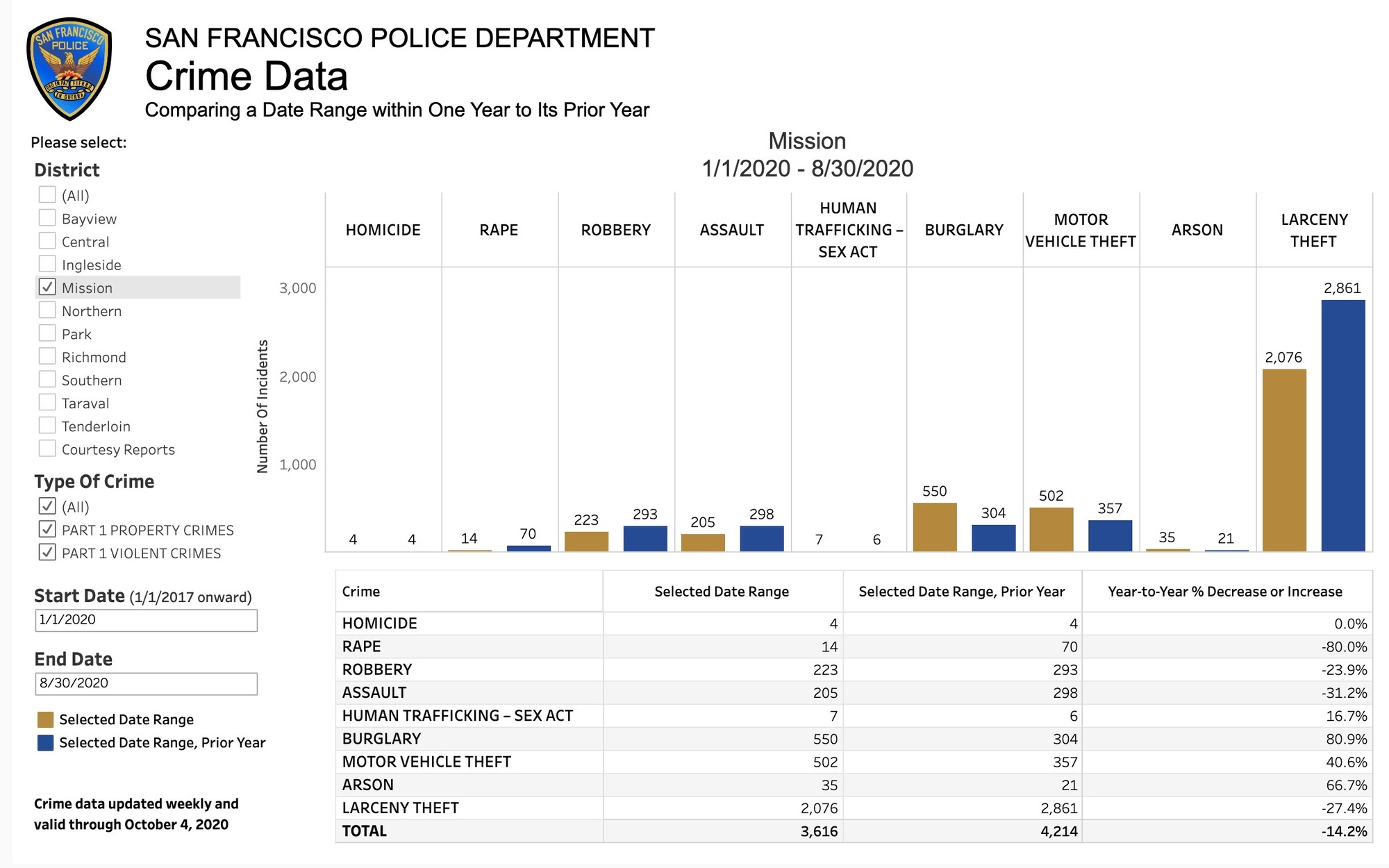

Compared to 2019, burglaries in the Mission Police District (which includes the Castro) are up 80.9%. Vehicle thefts are up 40.6%, and arsons are up 66.7%.

Not every crime category has increased — assaults and robberies are down, likely due to fewer people getting out and about during shelter-in-place.

But Aiello says she's heard from numerous business owners and residents who've been dealing with smashed windows and break-ins for years, and would like to see the cameras installed.

"When I meet with neighbors and police, one of the first things police suggest is installing cameras," said Mandelman. "But I think cameras always raise privacy concerns."

Maintained by Mission-based Applied Video Solutions, the cameras would only be installed on homes and businesses with their owners' permission. Aiello says the exact number and locations of the cameras haven't been decided this early in the process. If it moves forward, they'd likely be chosen based on crime data and consultations with SFPD.

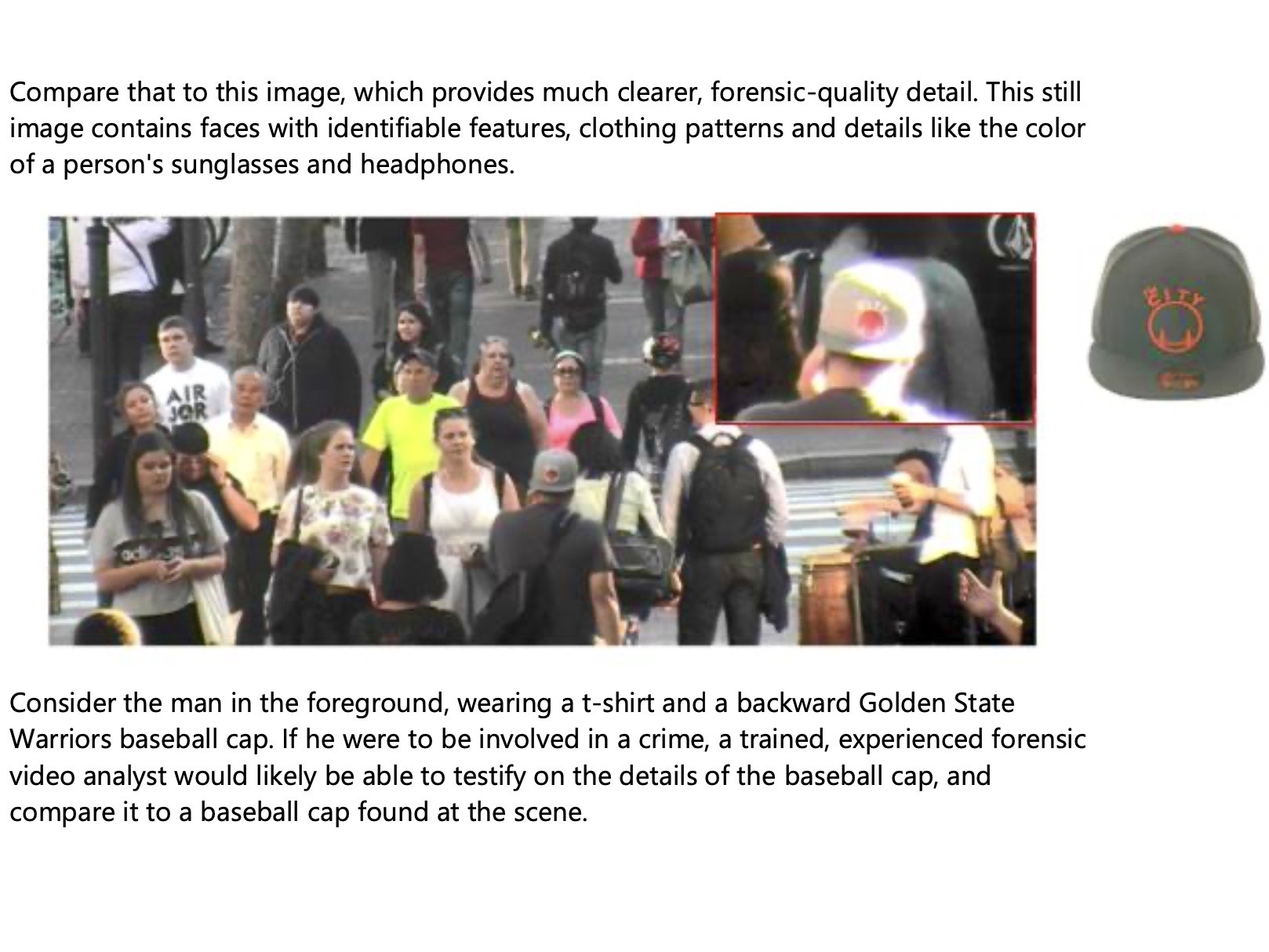

The high-definition cameras have video quality that's far superior to home security cameras like Ring or Nest, or the user-based app Citizen. They also time-stamp footage and use a larger field of view, making the resulting videos more compelling as evidence in court. Audio is not recorded, and all footage is deleted after 30 days.

The security camera footage would not have facial-recognition technology (which is banned in San Francisco). Larsen told the Times he also personally opposes its use.

Aiello says that access to the camera footage, which will be recorded 24/7, would be overseen by a neighborhood coalition. If someone needs access to the footage — like police, a crime victim or a defense lawyer — they'd have to send a request to the coalition.

With the plan still in its early stages, Aiello says she's not sure how the members of the coalition will be chosen.

The possibility of installing cameras comes at a critical juncture for the Castro CBD, which is funded through an assessment fee on property owners in the Castro area.

The CBD — which was just renewed by property owners for another 15-year term — uses that money to clean and brighten the neighborhood, promote public safety and lobby for larger, city-funded improvements. Those city grants, along with private donations, help flesh out its overall budget.

But with the city's budget deficit ballooning and a recession underway, the CBD has had to cut back significantly on spending. Its 2020-2021 budget is $866,274, down from $1.1 million in 2019-2020. (That's despite a sizable increase in the assessment fees on property owners, which rose from $534,000 in fiscal year 2019-2020 to $819,403 in fiscal year 2020-21.)

The cutbacks have led to some hard choices, including the possibility of laying off Cody Clements, the SF Patrol Special Police officer who guards the neighborhood. Most of his roughly $98,000 salary is paid by a grant from the city's Office of Economic and Workforce Development (OEWD).

The CBD has secured an approximately $200,000 OEWD grant for this fiscal year, but Aiello says she and the Castro Cares leadership team are still discussing the best use for the funds.

She's not sure whether the OEWD grant money can be spent on the maintenance and operation of the camera network. "I need to learn more about the grant process."

Maintaining the cameras could be more costly than continuing to employ Clements. Lorraine Lewis, the director of business planning and administration for the Tenderloin Community Benefit District (TLCBD), says her organization spends $136,000 a year to maintain, insure and staff its 90-camera network. Almost all that funding comes from grants.

The cameras' impact is also unclear. Lewis says she's not sure whether the cameras decreased crime in the Tenderloin, or otherwise served as a deterrent.

What she can say is that the camera network has provided greater coverage of any crimes it captures, creating a chain of evidence that can be used by a public defender or the office of District Attorney Chesa Boudin.

During a Tenderloin CBD meeting about the cameras in July, Boudin told the Times that he has mixed opinions on them. He likes that they can save the city money on policing; a single SFPD drug bust costs about $20,000, whereas a camera can capture similar evidence for a much lower cost.

But he's not sure how useful they are for arresting high-level crime ring leaders, rather than minor players on the sidewalks. And he's wary of the potential implications of individual citizens being empowered as crime-fighters, as many important laws that regulate sworn officers — including the city's laws on facial-recognition tech — don't apply to them.

Given the current conversation around policing, the potential police abuse of the technology is another concern. The SF Examiner recently reported that the Union Square BID let SFPD conduct live surveillance through its cameras during the George Floyd protests.

Saira Hussain, a staff attorney and privacy activist with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, told the Examiner that the surveillance was "extremely concerning," and could have a chilling effect on protesters' First Amendment rights.

Aiello says the Castro CBD is still in a very early phase of deciding whether to install the cameras. She plans to conduct significant community outreach, and despite the shelter-in-place order, believes that can be done virtually.

Should the security cameras be approved, it's unclear how the Castro CBD will pay for their maintenance. Aiello says they're still discussing it, and it's possible the cameras may ultimately prove to be too expensive.

The next meeting about the cameras will be on Sept. 24 at 10 a.m., when the Castro CBD's Services Committee will hear a proposal from Applied Video Solutions. The virtual meeting is open to the public.

Mandelman anticipates both enthusiasm and concern from neighbors about the issue.

"The Castro CBD is going to need to think long and hard to come up with policy and protocols that the material they collect is used in a way the neighborhood is comfortable with," he said.

* This article has been corrected to show that the Lower Polk CBD did not fund its camera network via Chris Larsen. Lower Polk CBD executive director Chris Schulman tells Hoodline that the funds came from a negotiated mitigation settlement with California Pacific Medical Center (CPMC). "Some funds went to Lower Polk Neighbors for alley and placemaking improvements and $1,150,000 went to the Lower Polk CBD over a several year period as partial seed money to start the CBD and go through the formation process, and partially as funds to be used at their discretion for operations. $150,000 was used as seed funds, and $1,000,000 was used for operations over a two-three year period of time. It was with these discretionary funds that the cameras were funded." Schulman added that CPMC did not stipulate how the funds should be used.