Writing with your mind? That's just what one paralyzed man has been doing with the help of some Stanford University researchers and microchips implanted in his brain.

The man, who lost practically all movement below the neck after an injury in 2007, is a participant in a study recently published in the journal Nature. Researchers placed two devices called brain-computer interfaces, each the size of a baby aspirin, into his brain. These pick up brain signals relating to hand movement.

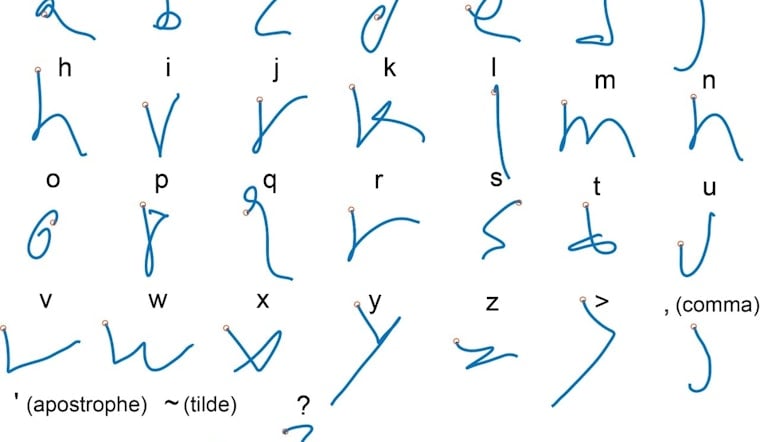

After that, the man simply had to imagine himself writing. The chips picked up the neural signals his brain generated to carry out the movements he imagined, then artificial-intelligence software decoded the signals and surmised his intended hand and finger motion.

Researchers have been using brain-computer interfaces to allow people to communicate who'd lost the ability to move or speak, but most research has been focused on gross motor skills and typing with computer cursors, according to the study authors. Instead, this effort focused on handwriting — and with spectacular success.

The man was able to write this way more than twice as quickly as he could using the old method, according to a Stanford news release about the research. In fact, he was able to produce 18 words per minute, not far from the average texting speed of non-paralyzed people his age of about 23 words per minute.

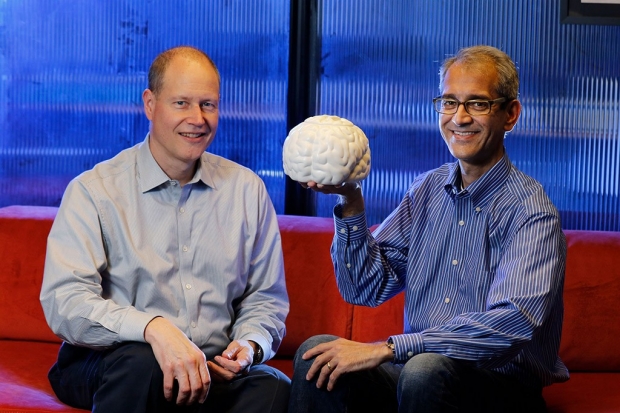

“This approach allowed a person with paralysis to compose sentences at speeds nearly comparable to those of able-bodied adults of the same age typing on a smartphone,” said neurosurgery professor Jaimie Henderson, one of the study's authors. "The goal is to restore the ability to communicate by text.”

What's more, the text the man produced had few errors. "Just raw typing without any autocorrect or anything, he can get about 95 percent of the letters correct, and then if you add autocorrect like you would on your smartphone, you can get above 99 percent accuracy," said research scientist Frank Willett, lead author of the study.

Jaimie Henderson and Krishna Shenoy, senior authors on the study Photo: Paul Sakuma / Stanford

"Temporally complex movements, such as handwriting, may be fundamentally easier to decode than point-to-point movements," like typing with a cursor, the study noted.

Willett said that the new findings shed light on a previous unknown: how long a paralyzed person's brain can actually recall the lost movements. “We’ve learned that the brain retains its ability to prescribe fine movements a full decade after the body has lost its ability to execute those movements,” he said.

The researchers believe brain-interface technology will eventually enable people with spinal cord injuries or neurological disorders to communicate faster on mobile devices.

“While handwriting can approach 20 words per minute, we tend to speak around 125 words per minute, and this is another exciting direction that complements handwriting. If combined, these systems could together offer even more options for patients to communicate effectively,” commented professor of electrical engineering Krishna Shenoy, another of the study's authors.