How do you get around Hayes Valley?

It’s a question that locals have been asking themselves since the early days of the city, and one we began taking a closer at last week.

Today’s issues around parking, crosswalks, bikes and drivers exist to a large part because a freeway was built through much of the neighborhood in 1959, then removed several decades later.

Following up on our look back at the construction of the freeway and Hayes Valley’s place in the freeway revolts in that era, here’s how the removal came about.

The instigation was the devastating Loma Prieta earthquake of October 17, 1989, because it damaged part of the Central Freeway spur that came over Market.

But the real reason was a concerted effort by local residents from a wide variety of backgrounds, who were interested in changing how cities were designed.

A New Type Of Transit Controversy

Demolishing neighborhoods in the path of freeway plans had by 1989 proven to be no longer politically feasible in San Francisco.

So, even though the Central Freeway had originally been intended as some sort of route all the way to the Golden Gate Bridge, there was no serious discussion about such a plan after Loma Prieta.

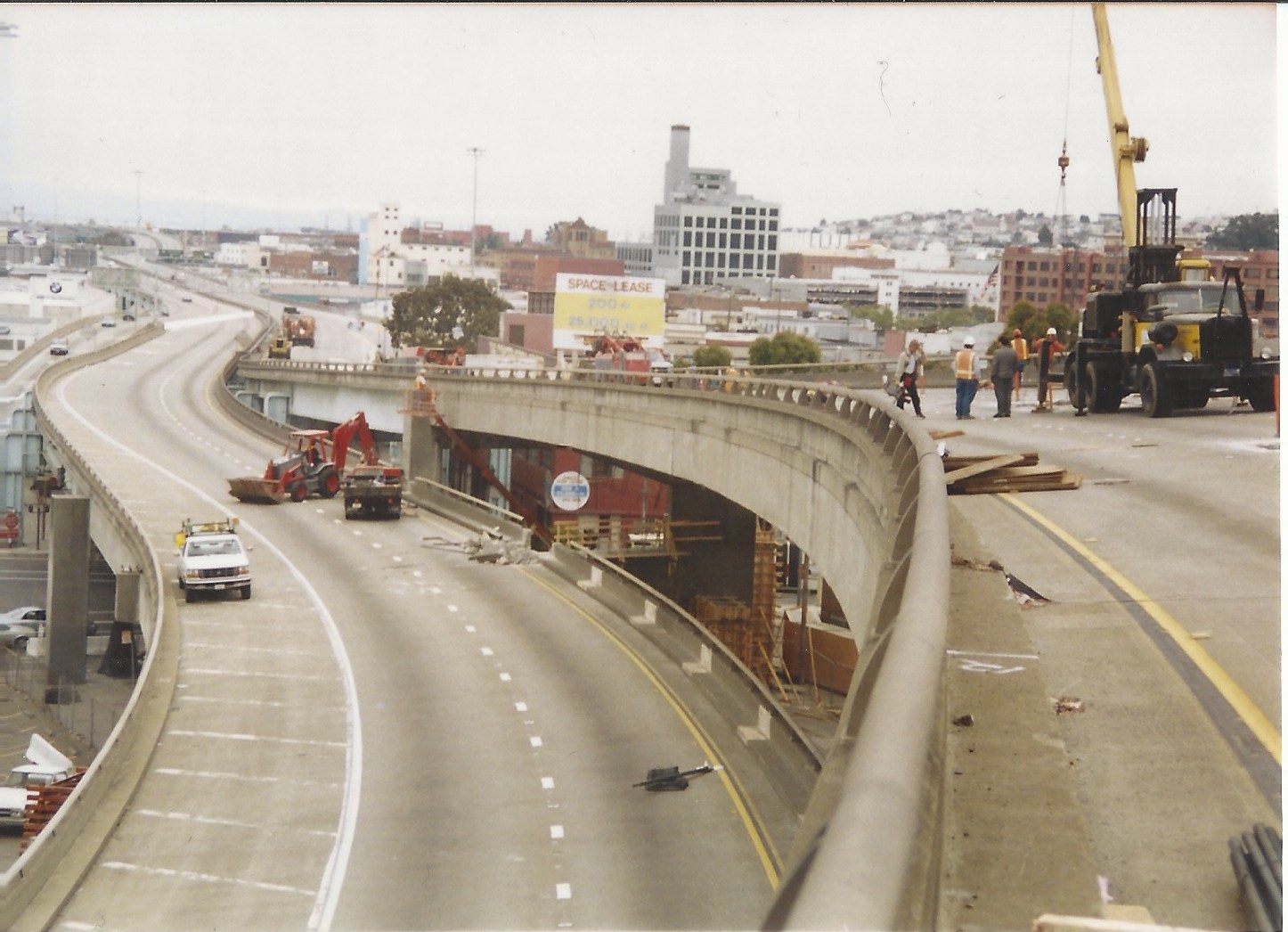

Photo via Madeline Behrens-Brigham

Photo via Madeline Behrens-Brigham

Meanwhile, the progress-leaning voters that had led the “freeway revolts” against the expansions in the 1950s and 60s had also been advancing a low-car vision in the following decades.

The Bay Area Rapid Transit system, for example, was funded in part by voters who feared more freeways. By the time of the quake it was providing an imperfect but functional new way for pedestrians to get around parts of the city and region.

San Francisco was becoming a new type of destination in the decades after the freeways were built. Inner city housing stock (and its residents) had been left to rot after decades of being denied home loans and “white flight” suburbanization. Rents were cheap, and for the many groups of progressive-minded people fleeing to San Francisco in the second half of the century, they made for great places to find people like them.

But the freeway spur had realized part of its goal. Residents and businesses in less-populated western and northern neighborhoods had come to rely on it to get south and east.

Hayes Valley, with its dense mix of retail and residential inherited from pre-car eras, was once again not just in the transportation crossroads of the city, but the political ones.

Remembering The Freeway Days

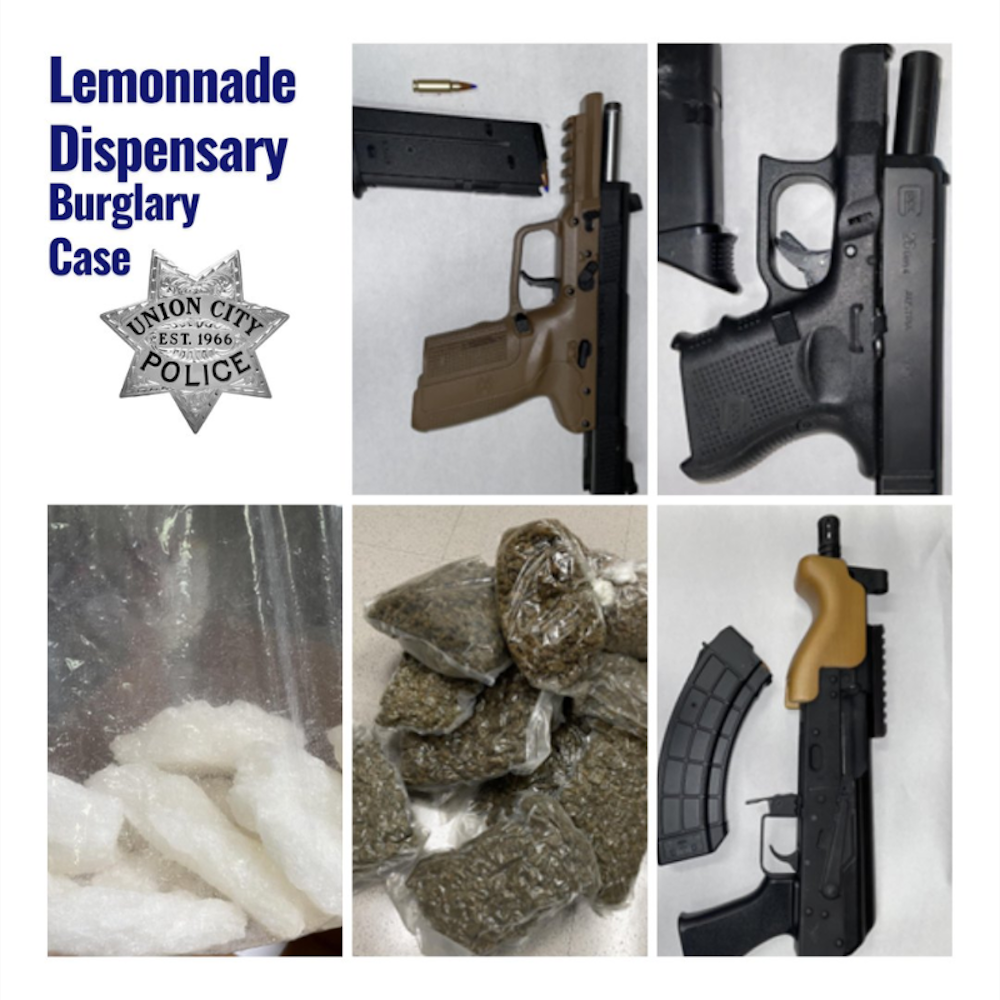

For the people living around it, the two-deck, 40-foot-high freeway spur was the pollution and crime-spewing blight that the freeway revolt activists had feared. And it was standing in the way of their vision.

Residents likened the structure to the Berlin Wall.

The east side, which ran along what is now Octavia Boulevard, boasted opera and jazz, thriving art galleries and shops catering to a wealthy clientele (not to mention City Hall, which was just three blocks away, and the rest of an economically burgeoning city center.)

Photo via Madeline Behrens-Brigham

Photo via Madeline Behrens-Brigham

The west side—what is now a busy strip of upscale stores, restaurants and apartment complexes—consisted of low-income housing, run-down victorians and scattered storefronts. One belonged to Madeline Behrens-Brigham a long-time resident, who lived and worked out of her collectables shop, Modernology.

“The freeway was the border, and you didn’t want to go under it,” remembers Behrens-Brigham. “We were called ‘the bad block’... You couldn’t get a pizza, you couldn’t get a taxi; the police wouldn’t even come here.”

The freeway was also a hotbed for drug dealing, prostitution and gang activity.

“Lights would be shot out all the time,” said Behrens-Brigham. “In the morning the hookers would line up underneath and construction guys would pull up with their trucks; they wouldn’t even move off to a side street they’d just be serviced right there.”

Meanwhile, as FoundSF has detailed, other constituencies wanted to keep the freeway. Business owners, particularly auto dealerships in the Van Ness area, were worried about losing customers. Residents of western neighborhoods, including some long-timers plus newer arrivals, were afraid that removing the freeway would increase their commute time.

Photo via Madeline Behrens-Brigham

Photo via Madeline Behrens-Brigham

The city ended up removing another notably damaged, previously controversial freeway on the Embarcadero after the quake. But the state transportation agency, Caltrans, decided in 1991 that much of the section north of Market should stay, despite pushback from Hayes Valley residents and a broader coalition of supporters.

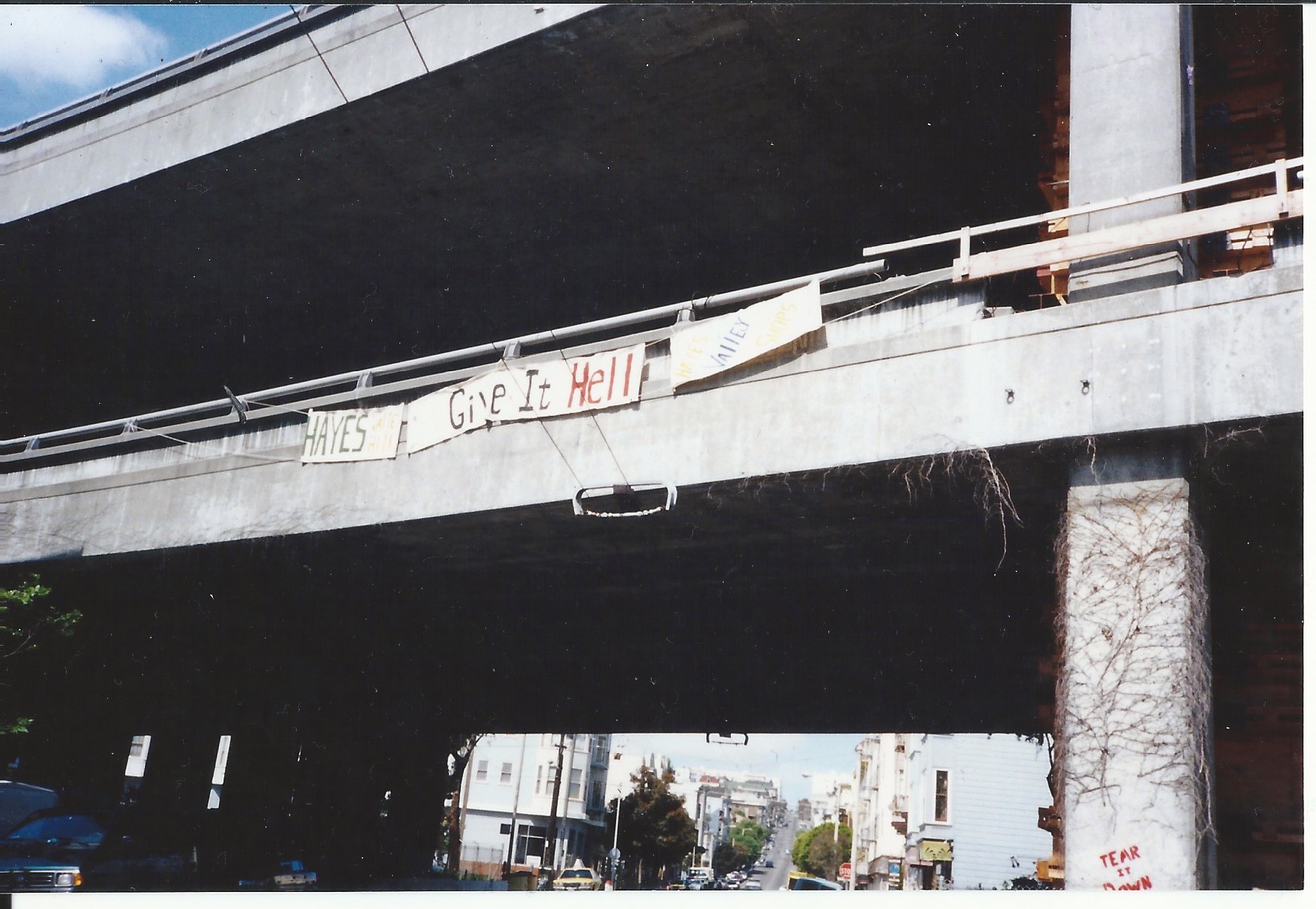

The neighborhood became the scene of a major confrontation in what FoundSF calls “the Second Freeway Revolt.”

Here’s our historical timeline of the convoluted debates of the 1990s that resulted in the Hayes Valley we know today.

The Central Freeway Revolt Timeline

1992: Caltrans, under pressure from Hayes Valley community groups (notably the early efforts of the Hayes Valley Merchants Association) and members of the board of supervisors, takes down the badly-damaged sections of of the spur running to Franklin and Gough at Golden Gate. The undamaged connections to Oak and Fell remain.

1995: The Board of Supervisors deliberate over the damaged freeway. Feeling pressure from both Caltrans and citizens advisory groups, they appoint the Citizens Advisory Task Force to study the issue and come up with a policy that reflects the needs and wants of the community.

The task force finds that most people want the freeway gone, so the BOS requests that Caltrans look into replacing the structure altogether. Caltrans ignores their request, a San Francisco Chronicle article reports, in favor of a $40 million plus demolition of the upper level and retrofit so the freeway can take traffic from both directions.

Photo via Madeline Behrens-Brigham

Photo via Madeline Behrens-Brigham

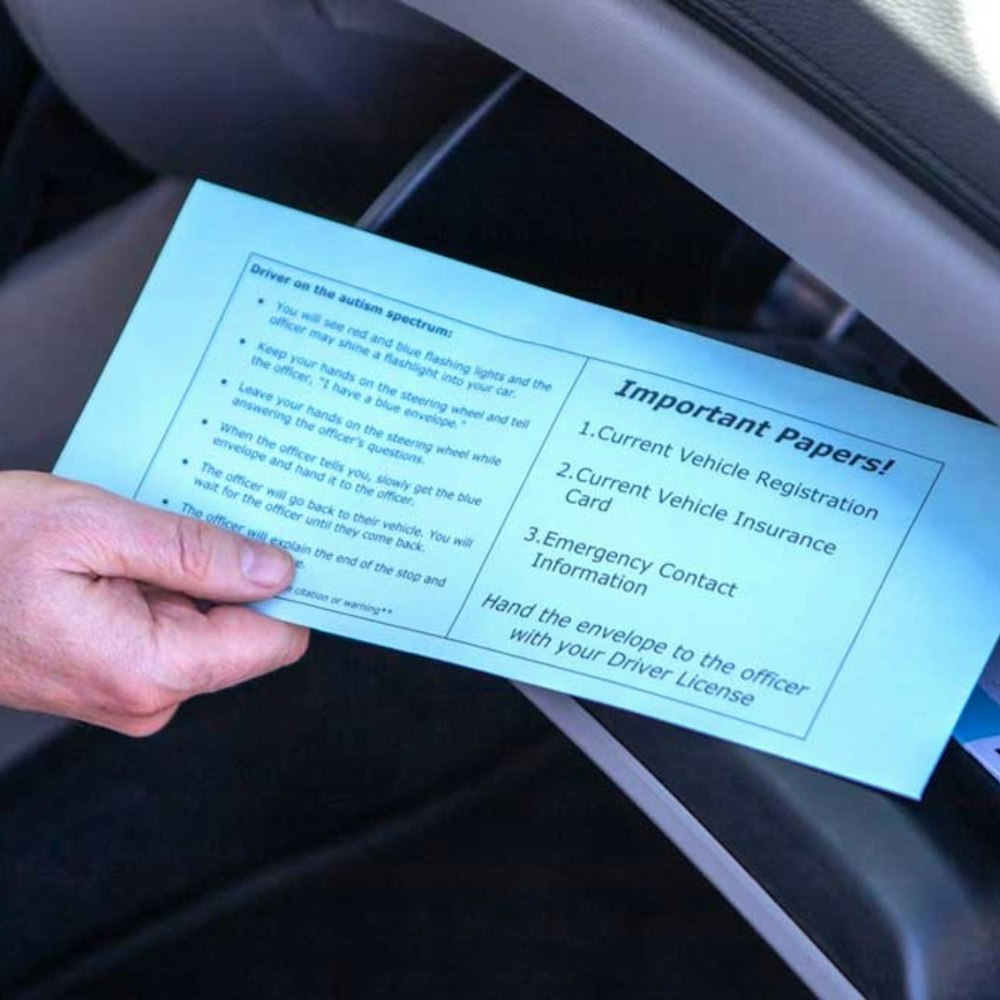

August 26, 1996: Caltrans begins to demolish the rest of the top deck. To prepare for certain gridlock, the Department of Transportation and Department of Parking and Transit leads campaigns urging commuters to seek alternative ways of getting to work, like public transit, cycling or, if they must drive, car pooling.

“[E]xperts predicted gridlock in all directions.” Chronicle writer John King remembers in a retrospective Chronicle article from 2003. “Traffic helicopters circled overhead to film the backup while bureaucrats waited by ramps with boxes of doughnuts for frazzled drivers.”

Whether from the awareness campaign or the overdesign of the freeway in the first place, traffic did not prove to be a problem.

Sue Bierman, then a supervisor and a leader of freeway revolt since the 50s, uses the outcome to argue the latter – that San Francisco never needed the Central Freeway to begin with. Her claim is backed by Mayor Brown, who, in turn, urges Caltrans to raze both decks and apply the $40 million to a replacement plan.

Propositions H & E

The issue finally hits the ballot box in 1997. At this point, the upper deck of the freeway is history, and the freeway war has, by and large, boiled down to one question: should we restore the freeway north of Market, or should we tear it down and replace it with a boulevard?

Thus, Proposition H makes it’s way on the ballot. A “Yes” vote means that Caltrans will embark on a $53.7 million project to rebuild, widen and retrofit the freeway from Mission to Fell Streets. A “No” means back to the drawing board.

The measure is largely supported by the Coalition to Save the Central Freeway, a group of mostly Sunset and Richmond District residents who, in just 4 weeks, gather 11,000 signatures to get Prop H on the ballot. The San Francisco Neighbors Association, another pro-freeway group, subsequently places one thousand pro-freeway signs throughout the city.

Photo via Madeline Behrens-Brigham

Photo via Madeline Behrens-Brigham

Meanwhile Supervisor Leland Yee, an ardent freeway supporter, says in the SF Chronicle that a surface-street alternative would be “detrimental to our air quality” and that “rerouting traffic, installing new signals, and widening certain existing streets would all need to be paid by San Francisco taxpayers.”

Prop H passes with 53 percent of the vote.

Some people blame the outcome on lack of coverage in the political press, others cite disorganization among progressive voters. Either way, those living around the freeway are devastated. A core group of activists, including Patricia Walkup and Robin Levitt, meet in early 1998 to figure out how to get the measure back on the ballot that year. (Walkup is who Patricia's Green is named after, as you may know, and as Brian notes in the comments, you can see her active during one of the election years in the photo above, front center wearing black.)

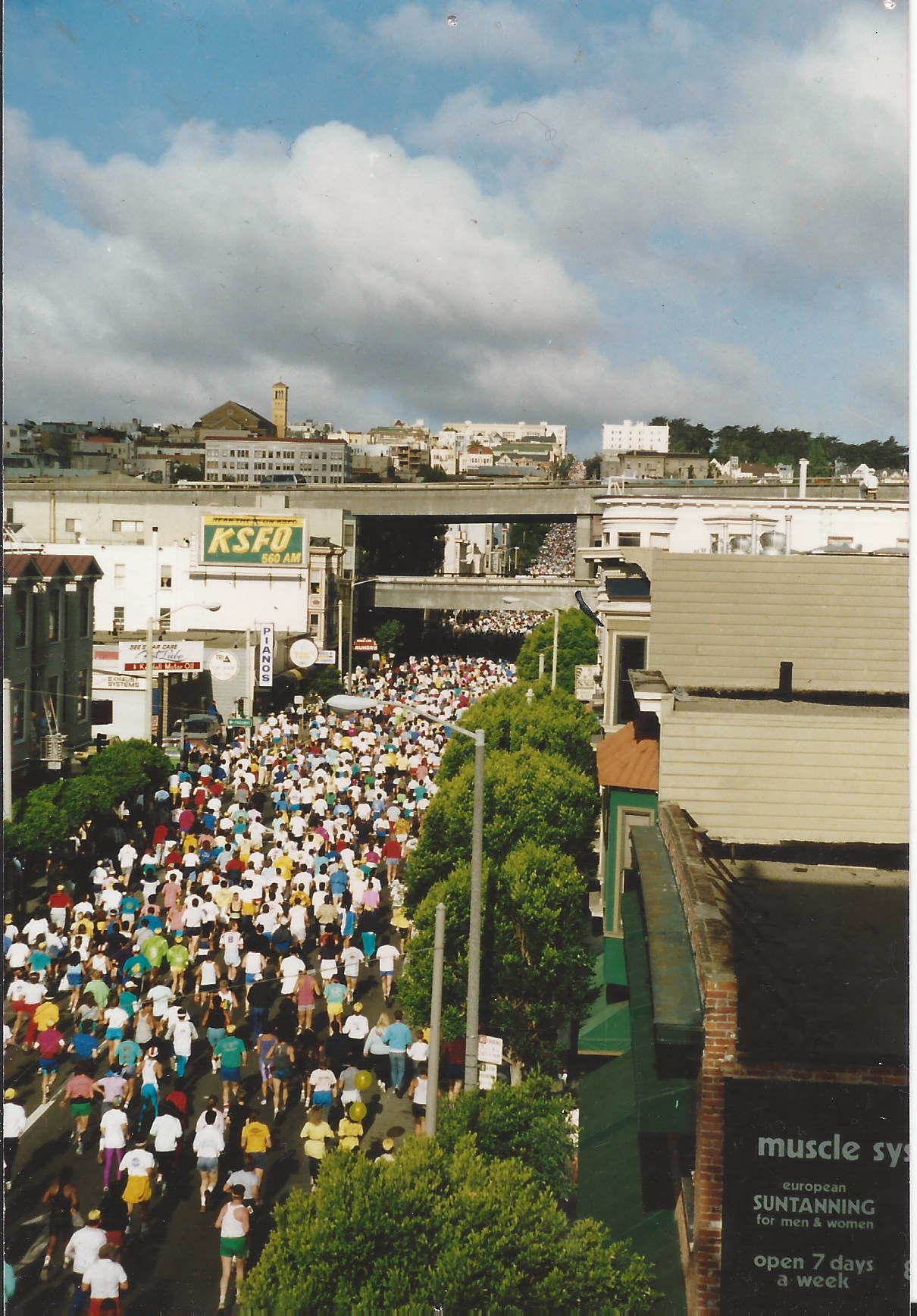

The result is 1998’s Proposition E, which asks voters, shall the city repeal Prop H and replace the freeway with a boulevard from Market along Octavia Street?

In an effort to gain support from the city’s progressive base, Prop-E supporters make appearances at the Jewish Festival, the Folsom and Castro Street fairs and the Latino Summer Fiesta in the Mission—only this time with a fresh approach: instead of condemning the freeway, they promote an attractive, state-of-the-art alternative that will efficiently move traffic west—Octavia Boulevard.

But the people had spoken in ‘97. And, perhaps for this reason, pro-freeway activists and west-side conservatives are less organized and less politically active that they had been with Prop H. Most of the “No on E” campaign is funded by Caltrans and the Department of Transportation, who suggest that the boulevard is poorly planned and a strain on taxpayers (Prop E is slated to cost $7 million more than retrofitting the freeway.)

A map of the former freeway route, as drawn by reader Tim O'Brien in response to our article last week

A map of the former freeway route, as drawn by reader Tim O'Brien in response to our article last week

Election day, November 3, 1998: Prop E passes with 54 percent approval, and the election gets 55 percent more voters than the previous year.

1999: The freeway war drags on. Freeway-backers want elevated ramps to Oak and Fell Street instead of a boulevard, and the issue goes back to the ballot box (Proposition J). Voters, again, opt for Prop E’s plan. Also on the ballot is Proposition I, which specifies that proceeds the city makes from selling or leasing right-of-way properties should help fund the Octavia plan and related efforts. It also passes.

2003: The Central Freeway north of Mission Street finally comes down. Final plans for Octavia Boulevard are approved.

Next: Building Something New

Since they first opened in 2005, Octavia Boulevard and Patricia's Green have become focal points not just for cars passing through, but for what has become a booming neighborhood.

We'll explore how the boulevard and the park got built, and much more, as we continue the series.