[Editor's Note: Mark Ellinger is a Tenderloin-based photographer and writer who documents the central city at his blog Up From The Deep. Here's an excerpt of his history of Mid-Market and Civic Center. You can find the full entry here. You can read his personal perspective of Sixth Street that we republished recently, here.]

Following the 1906 earthquake and fire, the stretch of Market Street between Powell and Polk developed as a lively theater and shopping district that by night was a sea of flickering chase lights and glowing neon tubes that seemed to stretch to the horizon on marquees announcing theater and cinema fare, and on towering blade signs like gigantic, fiery chart pins identifying each theater and department store along the broad and bustling thoroughfare; a protean street of dreams, alive with the pulse of the City.

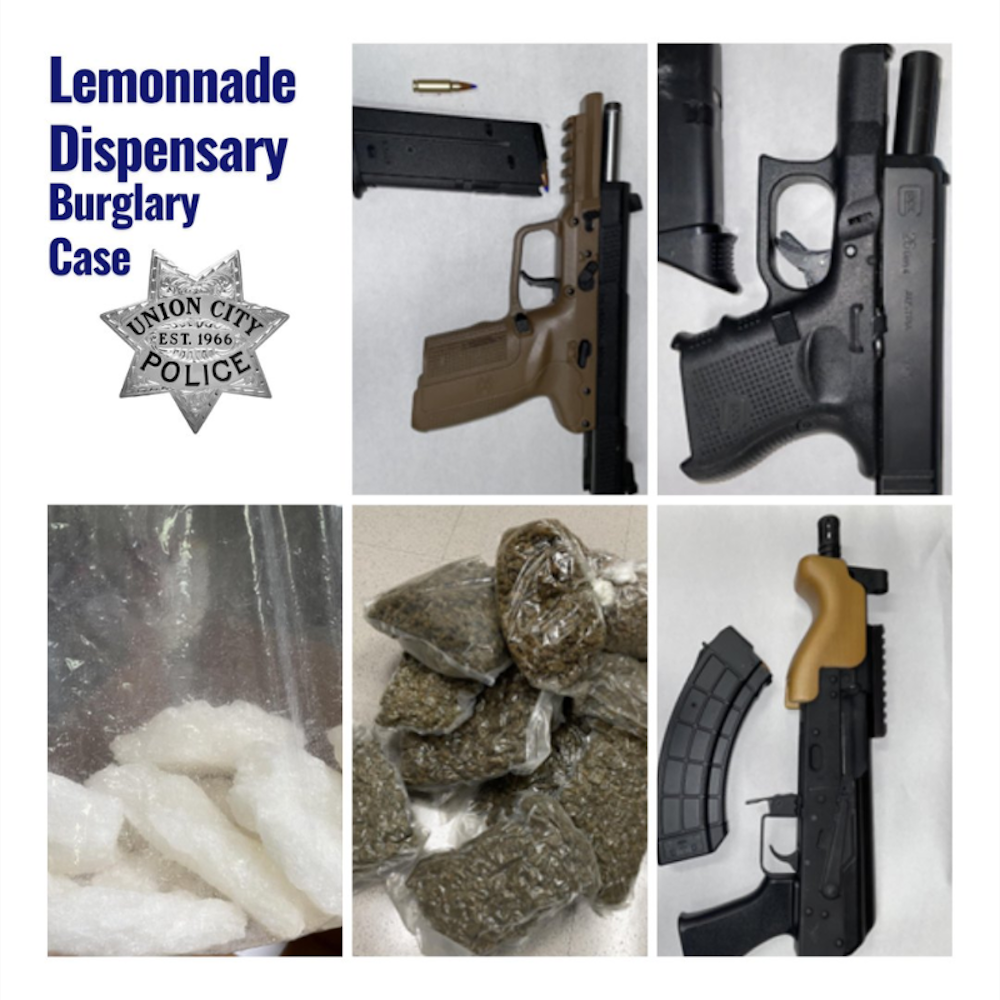

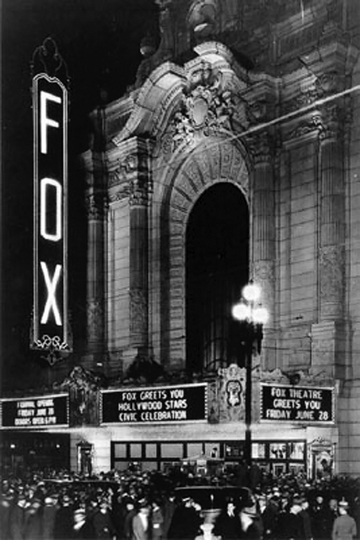

When in 1963 the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency demolished the celebrated Fox Theater, a San Francisco landmark designed by Thomas Lamb on the corner of Polk and Market, it was replaced by high-rise apartments and commercial space covering the entire block of Market Street between Polk and Larkin, named Fox Plaza in memory of the theater.

In 1964 BART began construction of its subway system, which for a decade turned downtown Market Street into a massive, gaping trench.

The destruction of the Fox was a death knell signaling the end of an era. The district lost much of its glamor when, under the 1967 Market Street Beautification Act, all of Market Street’s brightly-lit marquees and most of its neon blade signs were removed. When traffic was diverted away from the mid-Market area by BART construction, the district’s fate was sealed and it sank into a decline from which it has never recovered. Stores and theaters that had thrived for decades struggled on for awhile and then closed forever.

Mid-Market became a constantly changing landscape of liquor stores, fast food outlets, porn shops, check-cashing companies and gaudy storefronts, few of which have survived more than a few years. The downturn in quality and character of mid-Market commerce and a profusion of unused buildings and boarded-up storefronts have obscured the district’s glorious past and left in its stead an oppressive hollowness and blight.

Transience and decay have become ingrained, attracting derelicts, outcasts, and petty criminals from far and wide. One consequence of these changes, largely overlooked, has been a harsh decline in the quality of life for the area’s many long-time residents.

Marshall Square

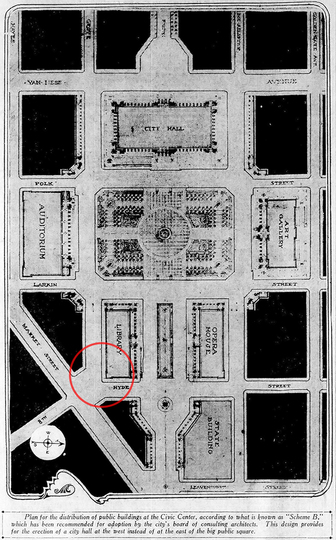

Marshall Square was a plaza that connected Market Street with City Hall Avenue (which was previously known as Park Avenue), a parallel frontage road for the old City Hall. When the old City Hall was ruined by the 1906 earthquake and fire, the design for a new Civic Center demanded the reshaping of grid lines. City Hall Avenue was completely obliterated and Marshall Square became part of the Hyde Street extension to Market. Opened in 1926, the office building and theater at the corner of Hyde and Market is the namesake of Marshall Square, though nowadays it is known only by the name of its theater, the Orpheum.

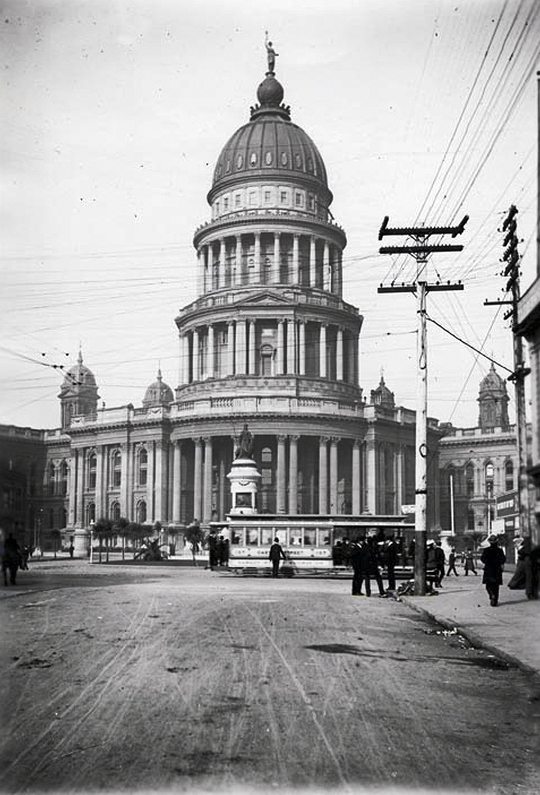

Designed piecemeal by seven different architects; shoddily constructed with compromised materials over a period of twenty-seven years at a cost of six million dollars; the old City Hall was a disgraceful mess, the malodorous embodiment of municipal graft. The stench of raw sewage frequently permeated the superstructure’s poorly ventilated chambers and corridors; a consequence of faulty plumbing.

Nine years after its completion, it was all but destroyed by the 1906 earthquake and fire.

Built in 1894 with money bequeathed by real estate magnate James Lick, sculptor Frank Happersberger’s Pioneer Monument mythologizes the story of San Francisco’s supposed “manifest destiny.” As told by the empire builders themselves (Lick was a founder of the ultra-exclusive Society of California Pioneers), it is an unabashedly romanticized story of empire building that depicts Native Americans as a docile and subservient people conquered by the Argonauts, nom de guerre of pioneering gold miners.

Contrary to both reality and Lick’s final wishes, the monument also places Mining ahead of Agriculture in order of importance, if not sustainability. Taken from the Great Seal of California, the figure that crowns the monument is Minerva, Roman goddess of wisdom and sponsor of arts, trade and technology. As a goddess born fully-grown, she symbolizes California’s direct attainment of statehood without first becoming a U.S. territory.

As things turned out, City Hall and the Civic Auditorium were the only Civic Center structures completed by 1915, just in time for the opening of the Panama Pacific International Exposition. The Civic Auditorium was in fact specifically designed for the PPIE and is one of the few exposition buildings still remaining. It was renamed the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium in 1992, in memory of the City’s renowned concert promoter. Thebeaux-arts Main Public Library was built in 1917 on the site proposed for the opera house. Following extensive remodeling under the direction of Italian architect Gae Aulenti, the building became home to the Asian Art Museum in 2003.

The new Main Library, erected 1993-95 and opened in 1996, was built on the site originally proposed for a library. 1922 saw the opening of the California State Building at 350 McAllister, proposed site of the art gallery. Today, the beaux-arts granite structure is home to the Supreme Court of California. Opened in 1932, both the beaux-arts War Memorial Opera House and its twin sister, the War Memorial Veteran’s Building (home to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art until 1994), were constructed on Van Ness Avenue, opposite City Hall. The site proposed for a state building, now part of the United Nations Plaza, is where thebeaux-arts Federal Office Building was constructed between 1934 and 1936.

As composed of these seven beaux-arts buildings, the San Francisco Civic Center is widely considered as one of the most successful manifestations of the City Beautiful Movement. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places in October 1978, it was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1987.