On Saturday, Gertie, an Australian Cattle Dog mix, was playing ball. By Tuesday morning, she was gone.

Gertie was the victim of a type of bacteria called leptospirosis. The potentially fatal bacteria has rarely been seen in San Francisco’s dog population, but this year, it’s rampant.

“At VCA [San Francisco Veterinary Specialists] alone, we have seen five documented cases in the past two months,” says SFVS veterinarian Elyse Hammer. In previous years, the hospital averaged one to two cases annually.

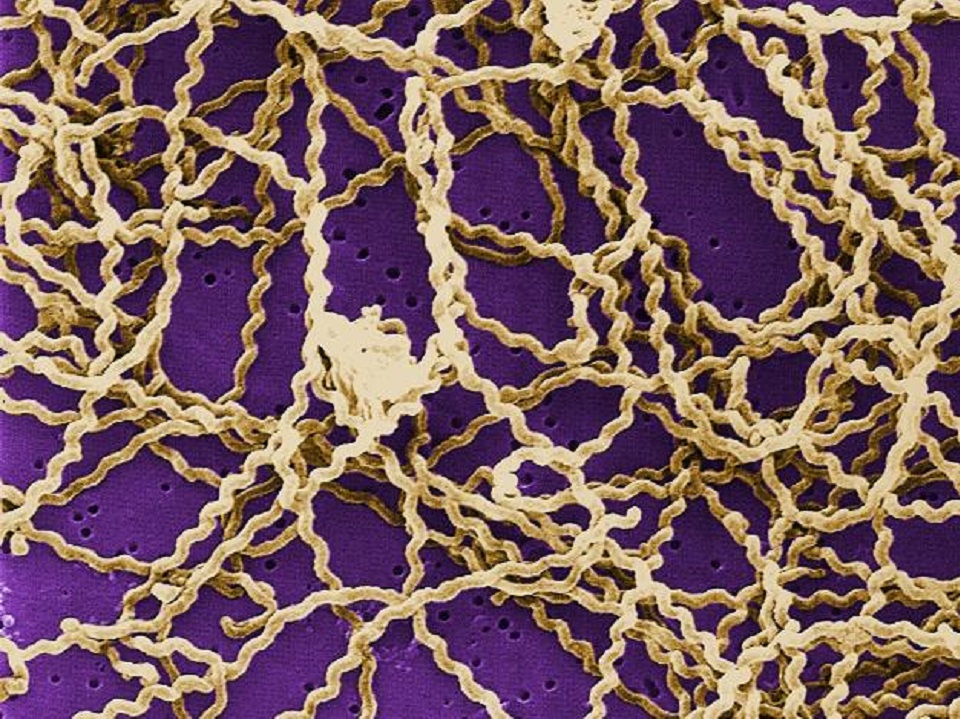

Leptospirosis spirochete, a flexible, spiral-shaped bacteria, is spread through the urine of infected animals, particularly wildlife like raccoons, skunks and coyotes.

If excreted in standing water, it can live for weeks and even months, infecting dogs and other animals tramping through or drinking from puddles. (Humans, too, are vulnerable to leptospirosis infection.)

Dr. Hammer speculates that this year’s marked increase in leptospirosis cases is likely due to the mud and puddles left by the city's recent heavy rainfall.

When the disease is caught in time, most studies show a 75 percent survival rate. Unfortunately, the initial symptoms can be hard to recognize. Hammer says symptoms are often non-specific and variable, and can include lethargy, decreased appetite, increased drinking and/or urination, vomiting or diarrhea.

Gertie’s guardian, Jeannine Giordian, noted that her senior dog initially seemed more tired than normal, but she thought Gertie was simply beginning to show her 13 years. Over the weekend, Gertie was eating normally, but her exhaustion continued, and she began to have a hard time walking.

On Monday morning, Giordian brought Gertie to her regular vet, but he couldn’t find any obvious signs of pain or illness. He drew some blood for testing and sent Gertie home.

The next day, Gertie’s blood work came back. “Her kidney values were off the charts,” says Giordian. “She was in renal failure.”

She immediately brought Gertie to the emergency room at SFVS, but the dog failed to respond to fluids and antibiotics. Giordian had no choice but to euthanize her.

Leptospirosis is preventable: the canine DHLPP vaccine protects against the bacteria, as well as against distemper, hepatitis, parvovirus and parainfluenza. Though the vaccine is not 100 percent effective, it is a dog’s best defense.

The problem is that most San Francisco dog owners have never heard of leptospirosis, so they don’t know to ask for the vaccine.

“I didn’t even know [the vaccine] existed,” says Giordian, who believes some San Francisco vets may be misinformed about the leptospirosis risk to city dogs. “Just because you live in the city, some vets think there’s no wildlife, but that’s not the case." Gertie spent every weekday in John McLaren Park, where wildlife is regularly sighted.

If your dog seems to be under the weather, “it is important to bring up to your veterinarian that your dog is out at the park or swims a lot, as these lifestyle components increase exposure to leptospirosis,” advises Dr. Hammer.

“I think the part that makes it most horrible is that it was preventable,” Giordian says. “Everyone should know that this is a disease that’s out there.”

The DHLPP vaccination is available at any veterinary office, and at the vaccination clinics hosted at Pet Food Express locations.