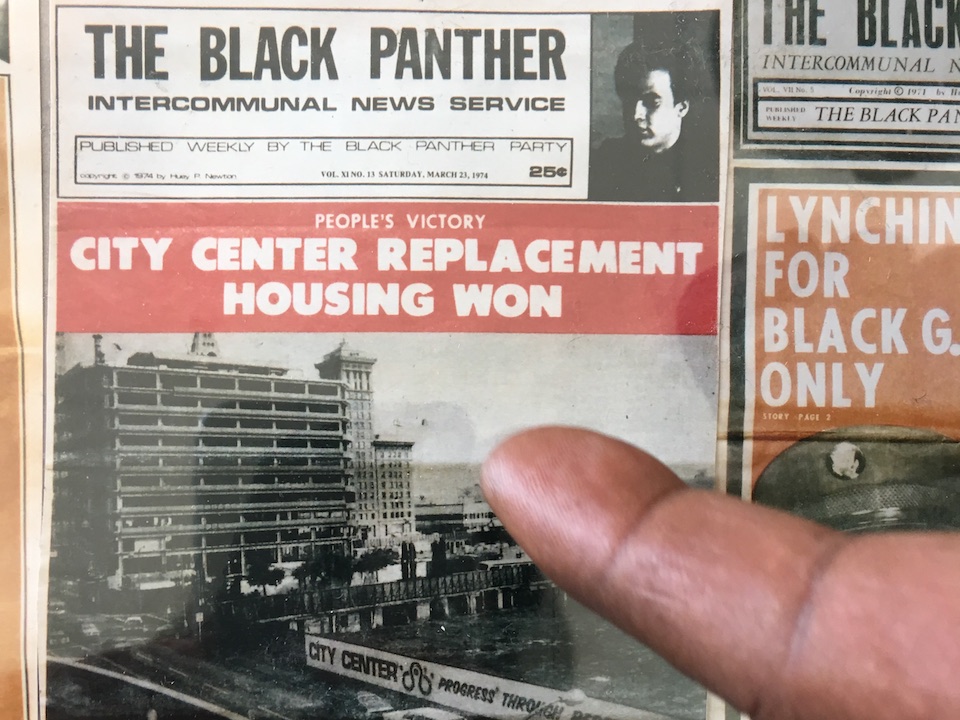

“The Mission tenants are in trouble,” stated a 1966 article by the civil rights organization S.N.C.C. “We demand decent housing,” read the front-page headline of an issue of The Black Panther a few years later.

According to former Black Panther Madalynn Rucker, people of color are still fighting for social justice when it comes to housing.

“If you close your eyes, some of the issues people are really concerned about now sound as if it were back in the 1960s,” said Rucker, now executive director of On Track, a diversity consulting group.

Today, she's part of a team organizing Stay In The Bay, a pop-up in Margaret Haywood Park from noon to 4pm.

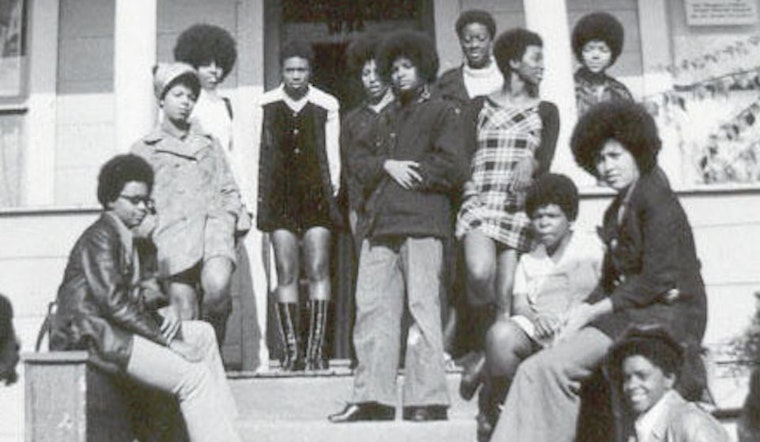

The first in a series of six, today's event will present images from the It’s About Time Black Panther Party Archive with workshops, resources, and experts who'll connect the housing issues and solutions from the past to the present day.

When Rucker and her team visited an exhibit at the Oakland Museum last year commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Black Panther Party, she was moved by the diversity of attendees.

She said she'd kept her party membership to herself due to the controversy often associated with the Black Panthers, militants who often dressed in paramilitary garb and appeared armed in public.

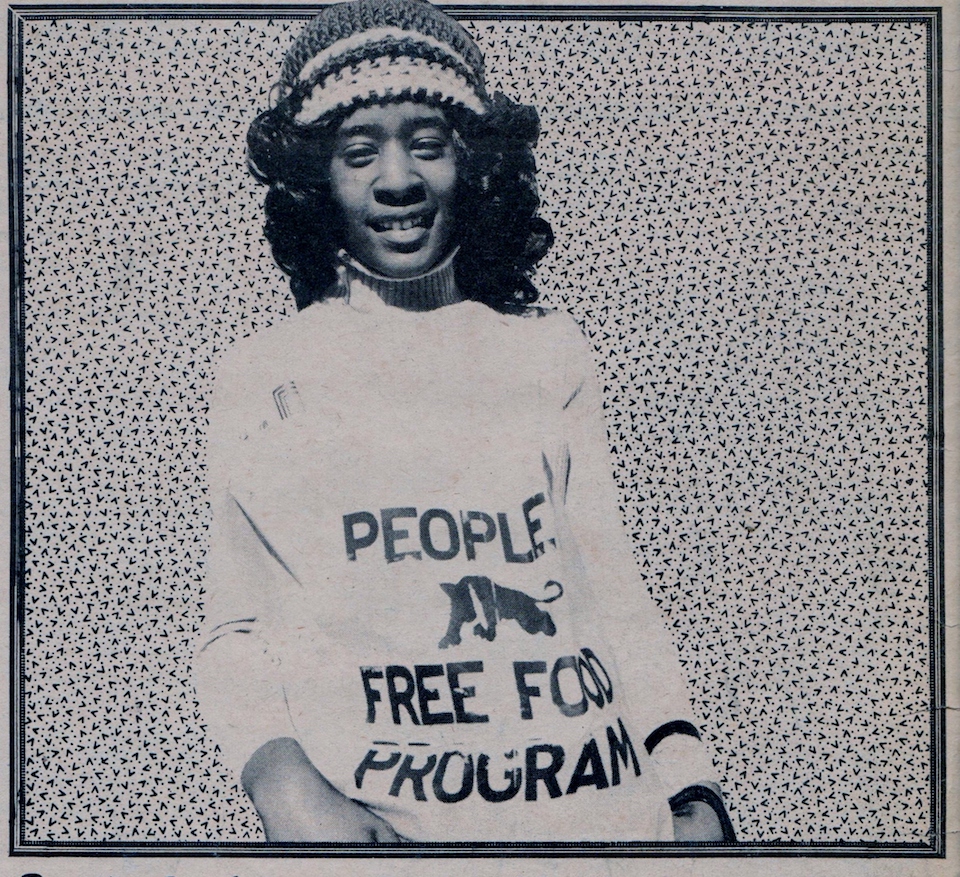

But the exhibit also reminded her of the work Panthers did in the community, such as a free breakfast program in Oakland that spread to many cities—and preceded the establishment of a federal program that exists to this day.

“Certainly we had a lot of missteps, but it also reminded us of the good that we did and that many people—because there were so many who came to see—recognized it,” Rucker said.

“Sometimes you just need little emotional reminders that we can fight for what we know is right. We changed our little piece of history.”

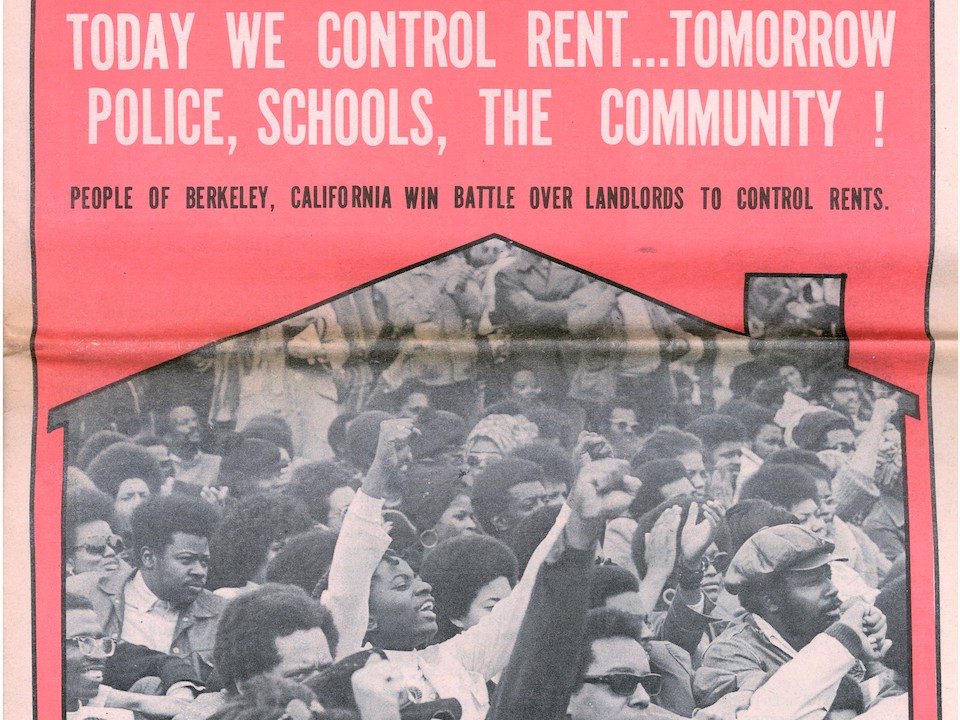

At Stay In The Bay events, attendees can browse artifacts such as newspapers and posters to see past examples of community organizing.

In an archival interview with Bobby Seale, one of the founders of the Black Panther Party, Seale described boycotting a store that declined to donate food to the free breakfast program by organizing a carpool to take shoppers instead to the Lucky Store, which supported the program.

“Next thing I know, I’ve got four other Lucky Stores donating food to us,” Seals said. “It’s economic power. It’s unity in the community.”

Billy Jennings, a curator and archivist who's helped organize the events, said relocation housing for people displaced by urban renewal was another example of the Black Panthers' ability to mobilize the community.

Thousands of minority residents were displaced in the Fillmore; in Oakland, a similar redevelopment took place in the city's center, demolishing more than a dozen blocks of mostly minority housing.

The Black Panther Party filed a suit to avoid mass displacement; the suit, according to Robyn C. Spencer, a professor at the City University of New York, led the City Council to agree to build the replacement housing.

Despite its name, Jennings said the party's membership included people of difference races throughout the country and around the world.

“We were there at a time when folks needed to hear that they had a right to struggle for what they believe in,” said Rucker.

For more information about subsequent events, email [email protected].

-1.webp?w=1000&h=1000&fit=crop&crop:edges)