Famous for its street-mapping technology, Google has partnered with the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) and Aclima, a sensor technology provider, to accurately map airborne pollution in West Oakland.

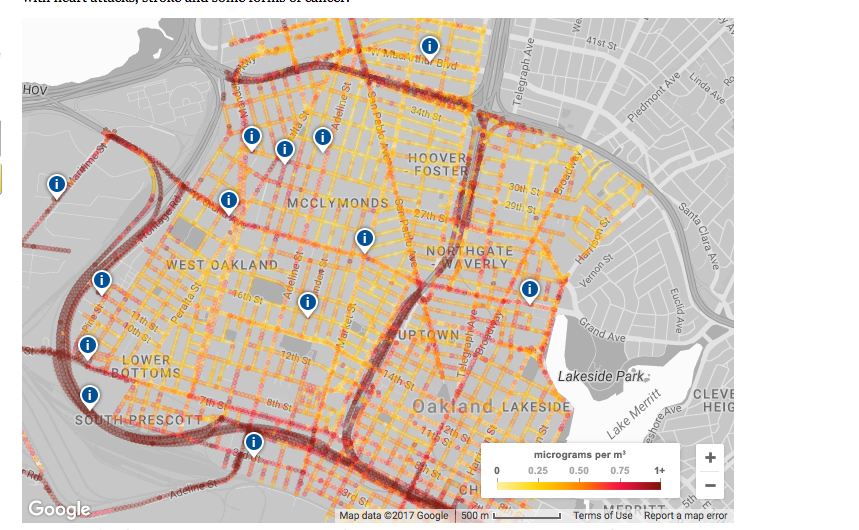

Starting in 2015, Google cars equipped with sensors drove more than four hundred miles of streets in West Oakland and parts of East Oakland at least thirty times on fifty separate days to assure an adequate sample size, altogether taking nearly 3 million measurements over 14,000 miles.

The study's results found that pollution levels varied between neighborhoods, and also on a hyperlocal level within neighborhoods. In some cases, residents near industrial operations or high-traffic corridors were found to be inhaling several times the amount of airborne toxins as neighbors a block away.

The study focused on particulate matter (PM) of 2.5 microns or smaller; for comparison, a single human hair is about 70 microns wide.

“At around four microns, particulate becomes respirable,” said Brian Beveridge, co-director at West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project (WOEIP).

“Ultrafine particulate [1 micron or smaller] can go into the deepest and most sensitive parts of the lungs and cross into the bloodstream," said Beveridge. "They can even pass the blood/brain barrier and enter the brain.”

Beveridge said ultrafine diesel exhaust coming from the 880 freeway is of particular concern.

“Diesel particulate has 22 known carcinogens,” he said. “They are tiny little packets of toxins going into your bloodstream.”

Before the Google study, West Oakland had only one fixed air quality monitoring station at West Grand and Poplar. According to Beveridge, using a single station to develop environmental policy for an entire neighborhood isn't effective.

“When ambient medians are what we’re constructing regulations off of, we’re also treating populations as an average mass,” says Beveridge. “But the data shows we are experiencing pollution as individuals, not as broad demographic groups.”

No stranger to citizen science, WOEIP is currently doing its own study of West Oakland air quality in partnership with UC Berkeley, with funding from EDF.

Beveridge said the two studies can strengthen arguments against further industrialization of the polluted neighborhood and port.

“Now people aren’t just coming in complaining, they’re coming in with data,” he said. “It’s powerful in changing the nature of dialog between community members and the people who are charged with protecting them.”

The findings could have significant impact on a recurring proposal to transport coal along freight lines in West Oakland and construct a terminal for coal export in the port.

Heavily industrial, West Oakland's problems with air pollution have worsened since the opening of the 580 and 880 freeways.

Because 880 is open to heavy trucks, communities in West Oakland, Chinatown and Fruitvale receive elevated levels of pollution, a situation Beveridge describes as a "tale of two freeways."

“Some folks have all the trucks passing through. Some don’t have any," he said.

"But everyone is getting the market benefit, even though people with lesser impact carry the greatest burden. Which is the definition of environmental injustice.”