This year marks the 40th anniversary of Muni's Castro station and the adjacent Harvey Milk Plaza. The station officially opened to subway service on June 11, 1980, less than two years after Milk's assassination.

To commemorate the anniversary, Hoodline is taking a look back at the history of the station and the plaza, and how we've gotten to where we are today.

Castro Station was one of seven underground Market Street subway stations built as part of the regional Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system project. Each day, thousands of Castro residents and visitors take the underground Muni subway, traveling downtown, to West Portal and beyond.

Later this year, the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency's (SFMTA) Castro Station Accessibility Improvement Project will add a new glass elevator to the station, in order to make it compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

The new elevator was originally intended to be part of a full demolition and renovation of Harvey Milk Plaza. But that project remains in limbo, as neighborhood group Friends of Harvey Milk Plaza (FHMP) faces pushback from some community members.

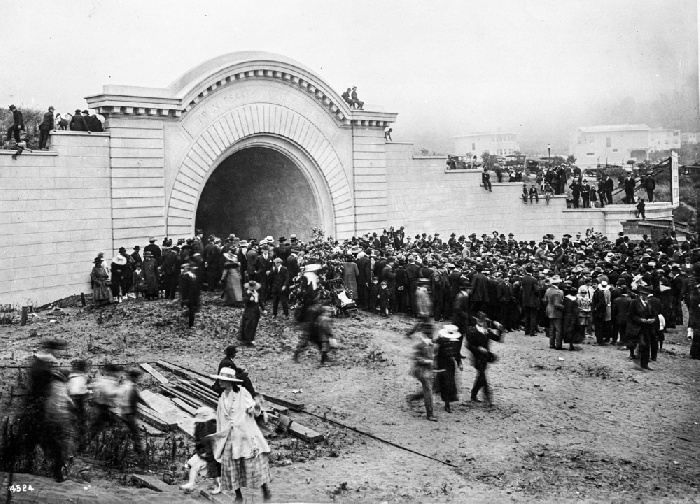

The story of Castro Station begins more than 100 years ago, with the Twin Peaks Tunnel.

Construction on the two-mile-long tunnel was completed on July 14, 1917. The tunnel connected the heart of the city with its "Outside Lands," ushering in a wave of westward expansion.

Terminating at the Beaux Arts-style facade of West Portal, the Twin Peaks Tunnel gave riders access to neighborhoods like Forest Hill, St. Francis Wood, Stern Grove, Parkside and Lake Merced.

The final pieces of the streetcar infrastructure were completed in 1917, and Muni's K-Ingleside train began running through the tunnel in 1918.

On its eastern side, the tunnel exited at Market and Castro streets. From there, streetcars continued above ground along Market Street past the 1922 Bank of Italy building, later known as the Bank of America building. (It's now home to SoulCycle.)

As traffic boomed in the post-World War II era, clogging Bay Area bridges, officials began to discuss how to relieve the congestion.

One solution was the construction of a regional public transit system. In 1962, voters narrowly approved a $792 million bond for the construction of the Bay Area's regional rapid transit system, BART.

BART construction broke ground two years later, in June 1964. Work commenced in the East Bay, with the Market Street subway section of the project launching in July 1967.

With stations constructed 80-100 feet below street level, the two-level Market Street Subway could carry both BART and Muni trains.

Stations were built at West Portal, Castro, Church, Van Ness, Civic Center, Powell, Montgomery and Embarcadero. (Forest Hill station, already part of the Twin Peaks Tunnel, was also folded into the system.)

As transit riders are aware, BART turns south at Civic Center, running along Mission Street, while Muni continues onward from Church to West Portal.

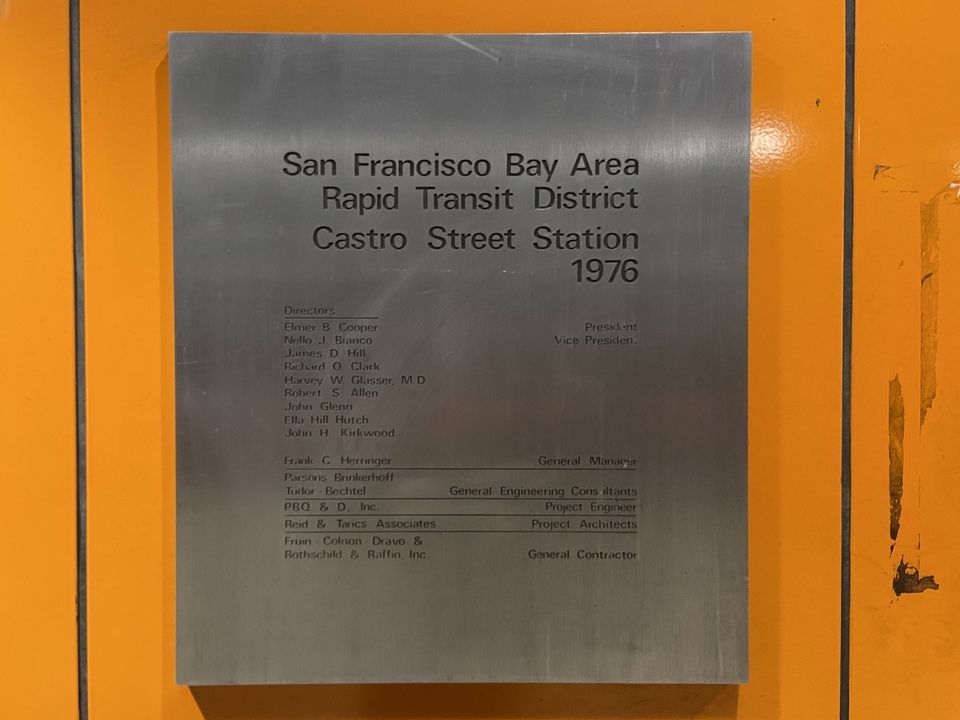

Reid & Tarics Associates (RTA) was the design firm responsible for West Portal, Castro, Church, Van Ness and Civic Center stations.

According to official documentation from SF Public Works, RTA and its project architect and designer, Howard Grant, were awarded two design awards for the project.

Civic Center station earned a U.S. Department of Transportation award in 1969, while Van Ness station earned a 1974 prize from the American Institute of Architects.

Castro Station includes two Market Street entrances: one on the north side, and a grand entrance on the south side of Market, at what is now Harvey Milk Plaza.

"In planning the five stations, I intended from the outset to give each one a distinctive character that would reflect its location," said Grant.

Original station features include a diagonal stairway down to the mezzanine, a large sunken garden with a clerestory window, a bridge over the plaza, planters and cedar benches along a serpentine wall.

"Castro Station was the culmination of the new Market Street redesign that was underway, with its signature red-brick paving," said Grant.

While service for BART officially opened on November 5, 1973, the Muni metro took longer, launching on February 18, 1980 with weekday N-Judah service. (The subway only began operating on weekends in 1982.)

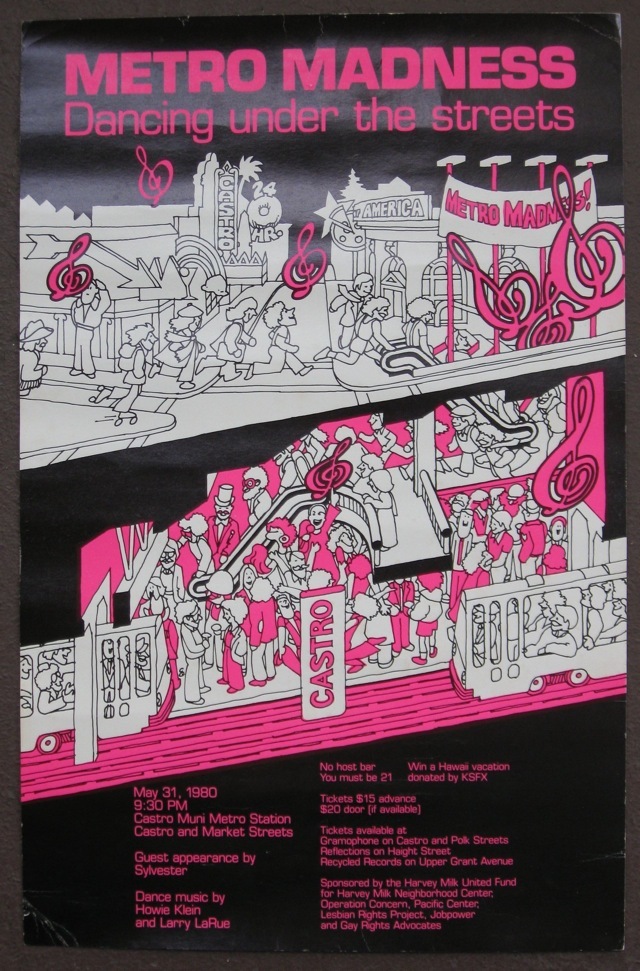

On May 31, 1980, approximately two weeks before subway service to the Castro launched, Van Ness Station hosted a grand-opening party on its platform, as a benefit for the Harvey Milk Fund.

Attendees of "Metro Madness" were able to ride a shuttle from Castro to Van Ness station. LGBTQ+ icon Sylvester was on hand as the special guest performer (the performance was videotaped).

Then, there was Harvey Milk Plaza.

According to a 1985 letter from Scott Smith to former District 3 Supervisor John L. Molinari, the Board of Supervisors designated the area at and around the station as Harvey Milk Plaza in 1979 — one year after the murder of Milk and Mayor George Moscone.

It wasn't until six years later that the plaza was officially dedicated in Milk's honor, as part of the 12th annual Castro Street Fair on September 15, 1985.

Large metal letters spelling "Harvey Milk Plaza" were placed on the bridge, and a bronze plaque was installed on one of the bridge columns.

For nearly a decade after the dedication, the plaza did not see any other major improvements. But in 1995, the Board of Supervisors passed a resolution calling for a "major civic space" to honor Milk at the location.

One of the Castro's most iconic images, a large flagpole flying the rainbow flag designed by Gilbert Baker, was added to the plaza in 1997. It was raised on November 7, the 20th anniversary of Milk's election win, and has become a worldwide symbol of LGBTQ+ pride.

By 2000, neighborhood group Castro Area Planning and Action and SF Public Works had come together to create a master plan for the area. This resulted in a design competition, led by the SF Arts Commission, to introduce a new piece of public art to the Castro.

One of the grand-prize designs was Christian Werthmann's “Pink Cloud," a cloud of pink steam intended to hover over the intersection of Castro, Market and 17th streets.

Another feature was a structure called “A House For Harvey,” to be located in Harvey Milk Plaza. But ultimately, the project was shelved for lack of funding.

Supervisor Bevan Dufty revived the "Pink Cloud" idea in 2009, but again, the project never came to fruition.

On May 21, 2006, which would have been Milk's 67th birthday, a permanent photographic tribute was unveiled on the fence surrounding the sunken garden (to which entrance had been blocked in 2004).

The 11 featured photographs depict different stages of Milk's life.

One of the photographers featured in the tribute is Daniel Nicoletta, a close friend of Milk's, who worked on his political campaigns and at his camera shop at 575 Castro St. Nicoletta is credited with organizing and planning the installation, in coordination with Dufty and State Senator Carole Migden.

In the 2010s, the plaza faced a few trials and tribulations.

In 2011, the large brass plaque honoring Milk and Moscone was stolen. The plaque was never found, and had to be replaced.

The original cedar benches on the plaza's street-level walkway were removed at some point, but new purple benches were installed in 2010. However, due to neighborhood concerns with undesirable street behavior, the benches were removed just two years later.

The prospect of upgrading the plaza was spurred by SFMTA's 2016 announcement of the need for the new elevator.

"[Our mission is] to reimagine Harvey Milk Plaza as a welcoming, vibrant space that honors Harvey's life and legacy, celebrates his enduring importance to the LGBTQ+ community, and inspires by acting as a beacon of hope to marginalized communities worldwide," said Andrea Aiello, president of FHMP.

Designer Perkins Eastman was selected in 2017 after an international competition. But since then, the project has seen many design revisions.

After significant community pushback, plans for a large on-site amphitheater were abandoned. A pink free-form structure, intended to take its place, has also been nixed.

In mid-2018, Aiello told Hoodline, her group realized that the plaza redesign project couldn't be coupled with the addition of the new elevator.

Now, the FHMP are preparing to release new renderings, in partnership with Perkins Eastman. Aiello believes this proposal will be a success.

"The current community-based effort has gotten the furthest," she said.

The plaza redesign received Phase 1 approval from the SF Arts Commission in 2018. It's begun the environmental review process and its first step, a Historical Resource Evaluation.

Grant agrees the plaza needs an upgrade. "Clearly, the plaza could use some loving attention after 40 years of neglect and minimal maintenance. The Milk memorial deserves to be dramatically improved."

"Hopefully, this will be achieved while retaining the historic features of the plaza," he said.

Special thanks to photographer Daniel Nicoletta for allowing Hoodline the use of his historical photos.

Nicoletta's first solo photography book on the LGBT journey, "LGBT San Francisco - The Daniel Nicoletta Photographs," was released in 2018. The book can be purchased online and at local booksellers.