This article, written by Mark Hedin, was originally published in Central City Extra's October 2015 issue (pdf). You can find the newspaper distributed around area cafes, nonprofits, City Hall offices, SROs and other residences – and in the periodicals section on the fifth floor of the Main Library.

It’s been 40 years since punk rock first reared its snarling, safety-pinned head. Although San Francisco’s thriving punk scene doesn’t always get its due, the rebellious music and community flourished here, characterized in large part by bands such as the Avengers and Dead Kennedys, whose pointed social commentary and songs of protest and angst placed them along the trajectory of creative dissent that, as poet-about-town “Diamond” Dave Whitaker has often said, went from “the beatniks to the hippies to the punks.”

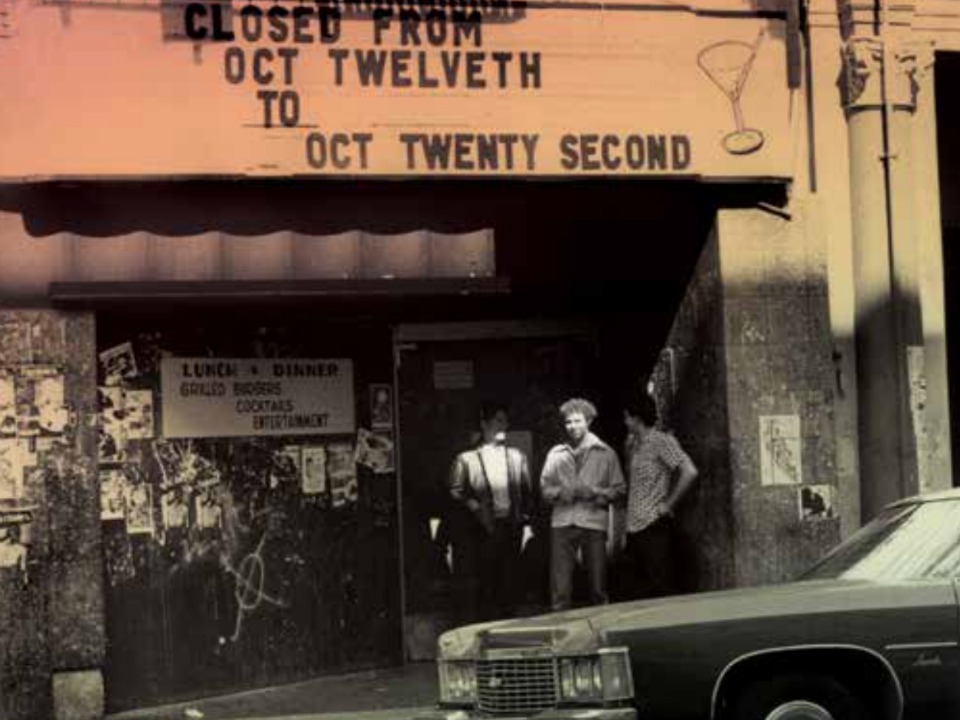

While the spotlight — and sometimes searchlight—focused on the “Fab Mab” Mabuhay Gardens and other North Beach clubs such as the On Broadway and, to a lesser extent, the Stone, down in the Tenderloin, the underground of the underground found itself a home. Anyone who was anybody could gig at the Mabuhay, but to play at Celso Ruperto’s Sound of Music club at 162 Turk St., you had to truly be a nobody.

Photo: Jeanne M. Hansen/Lise Stampfli

Photo: Jeanne M. Hansen/Lise Stampfli

“The Sound of Music was a dump, the sound system sucked, but it was a club where about anyone could play and most people could get in free or cheap,” White Trash Debutante singer Ginger Coyote recalled. Coyote has remained active in the punk scene over decades now, leading her band and publishing Punk Globe magazine out of L.A..

Today, the site is as quiet as it was loud back then, with a retractable black metal security gate stretched across the front and inside, mattresses, a ladder and debris visible through the glass façade, a real estate agent’s sign stuck on the exterior.

Photo: Google

Photo: Google

In September, a collective calling itself the Punk Rock Sewing Circle organized a series of events in San Francisco and Oakland celebrating 40 years of Bay Area punk. Among them were four walking tours, of the Tenderloin, SoMa, the Mission and North Beach. If you saw a group of about a dozen people standing outside 162 Turk on Sept. 24th, led by a fellow with a microphone and small speaker — not Del Seymour — that was it.

Other stops included the site of the Market Street Cinema, the Crazy Horse strip club next door to the Warfield, Oddfellows Hall and the 181 Club.

Sound of Music stalwarts Frightwig, Flipper, Toiling Midgets and Vktms were among the Punk Rock Renaissance acts appearing in concerts at 111 Minna and the Mission’s Verdi Club over the course of the week, and Sound of Music flyers were plentiful among the hundreds displayed at the various events.

Club owner Ruperto, usually known by his first name, took a cue from fellow Filipino Ness Aquino, the owner of the Mab, and began booking bands in late 1979 or early 1980 as an alternative to the drag shows he’d been hosting, said Ian Webster, who worked at both venues.

With the city bursting at the seams with misfits and outcasts, there were plenty of willing performers and before long, the Sound of Music was mostly a rock ’n’ roll club, providing a community for those kids.

“They really made it a place where we could go and be safe, because there was always shit going down, just like now,” said Paul Hood, who played there often in Toiling Midgets.

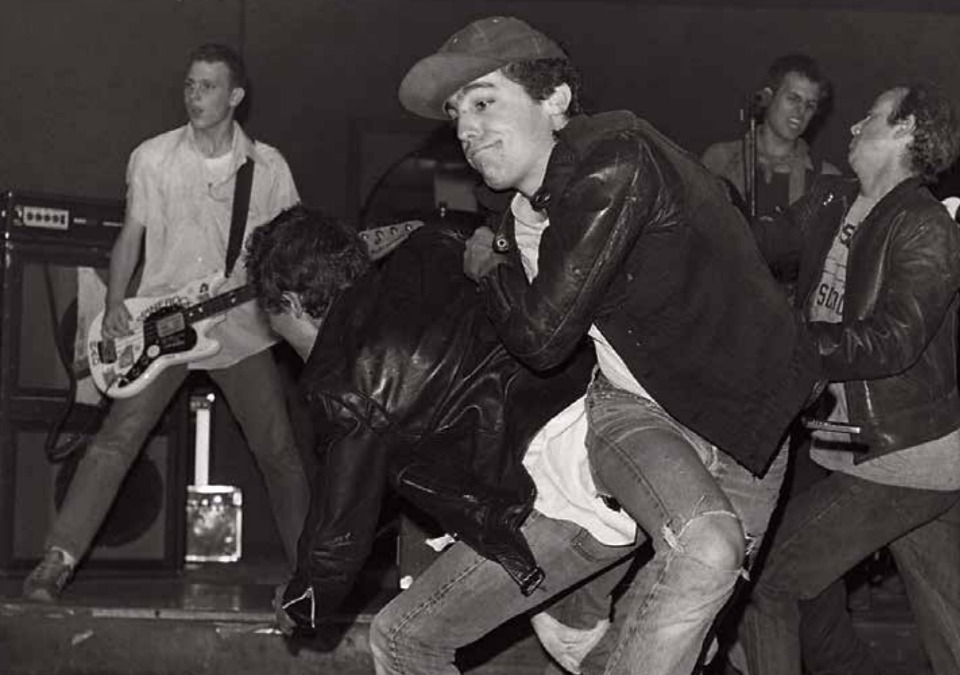

Slam dancing to the band Society Dog. (Photo: Bobby Castro)

Slam dancing to the band Society Dog. (Photo: Bobby Castro)

“For me it was the antidote to the shit of the ’80s: typical high school, ruled by the wealthiest kids with nose jobs and BMWs. Once I found the weirdos who liked to dress up and be silly, I felt liberated,” said Michele, an exile from the Peninsula. “When I think back on it, we were given four more years to play and not have to grow up. “I have a terrible memory. But for sure that time was super-important to me. I grew up on the Peninsula with friends I had known since kindergarten. In high school they morphed into assholes. It felt oddly akin to the entitled gentrification that has been going on in S.F. now. I felt very disenfranchised and chased out of my own life by rich, self-centered, clueless kids who were out of control, yet in control. I found my heart, my music, my politics, my values and my best friends in the punk scene.”

Many punk bands were already too big for the Sound of Music when it opened its doors to the scene a few years after the first wave broke. So no one saw the touring bands from New York’s earliest days of punk there: The Ramones, Cramps, Patti Smith, Television, Blondie and the like, nor the English bands that followed — the Sex Pistols had played Winterland in January 1978, after all. And the Avengers and Nuns, locals who opened that show, had already dissipated before Sound of Music even got started.

But for newer local bands such as Faith No More, Flipper and Frightwig, who went on to make names for themselves in the ’80s, the Sound of Music was an important launching pad.

“There was a movement happening there at the time and it just grew and grew and by ’82, the Sound of Music was happening in a regular way,” recalled Hood, who worked as a bike messenger, along with most of his Toiling Midgets cohorts to support himself while frequently gigging there.

“They started to bring in bands that could really fill the place — Gun Club from L.A., for example. “Some of these memories are hazy, but we played there with Flipper a lot in ’80, ’81. We were always paired and put together. We would be considered one of the bigger bands because we could put more people in the club.”

Other frequently appearing acts, such as Translator and Romeo Void, Hood recalled, reflected a transition that began to take hold moving away from punk to edgy new wave and pop. If a concert fell through for some reason somewhere else, there was always the Sound of Music.

Coyote recalled: “When Agnostic Front was going to play the Mabuhay Gardens, a certain female who ran a distribution company used all her pull strings to get the show canceled. She accomplished in getting Ness to cancel the show. But it moved to the Sound of Music and was a sell-out show.”

Mia Simmans, who still performs around the city as Mama Mia and was back on stage with Frightwig at the Punk Rock Renaissance show at the Verdi Club, wrote of those early ’80s days: “Frightwig used to practice at Turk Street Studios, right across from the Sound of Music. One day I went into the club in the afternoon and asked Celso for a job. He looked me up and down and said I could start bartending that evening. I was 17."

"I saw all of the bands of the era during my stint there — it was great fun, loud as sin and about as dirty. Bartending was easy, as all everyone ever wanted (or could afford) were the $1 cans of beer, with the occasional shot of nasty bourbon thrown in on special occasions. Everyone was broke, pissed off about everything and having the time of their lives. If I didn’t like a band, I would throw half-full beer cans at them from the bar."

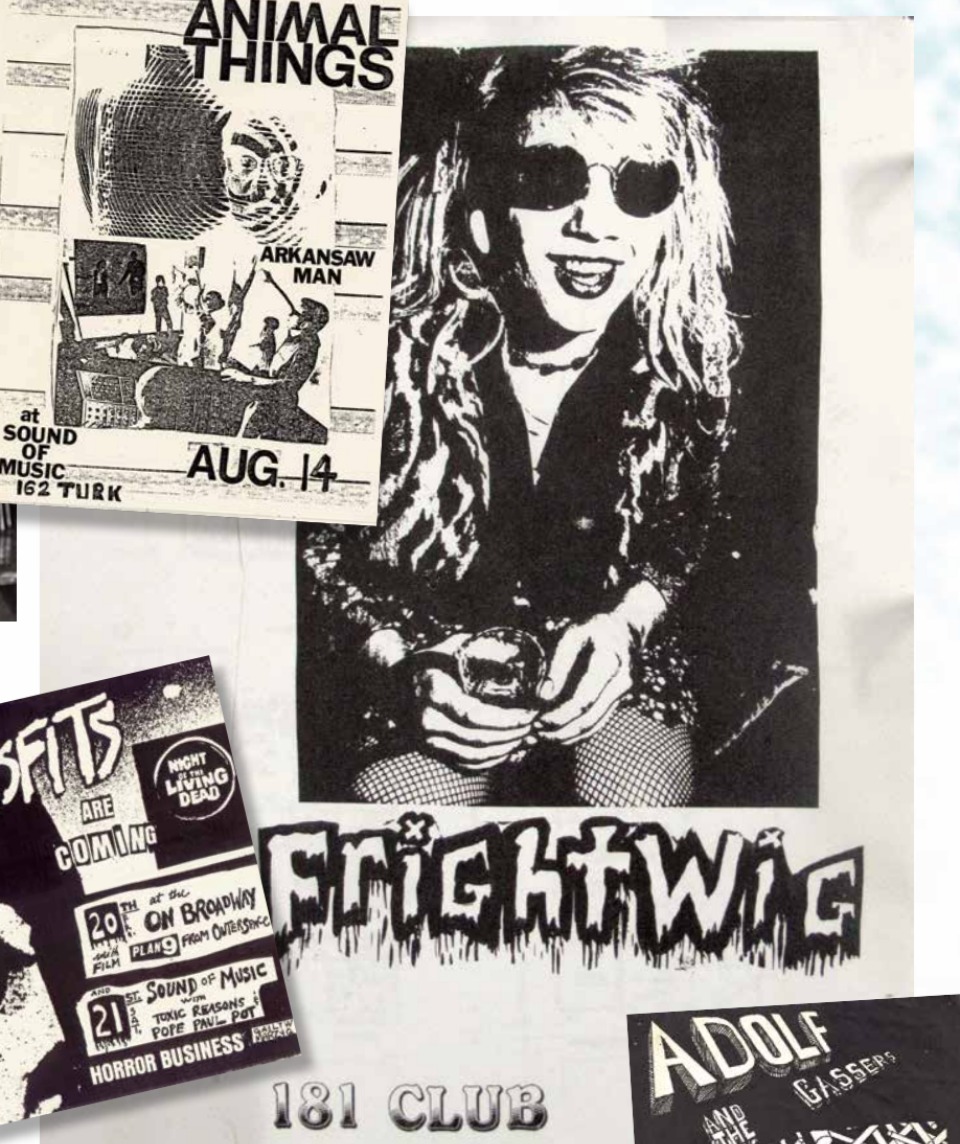

Flyers from the ’80s for Tenderloin shows. Adolf and the Gassers got some legal heat when a Second Street camera store noticed their name.

Flyers from the ’80s for Tenderloin shows. Adolf and the Gassers got some legal heat when a Second Street camera store noticed their name.

"The Sound of Music was more democratic,” Webster, who performed there, booked bands and worked the door, recalled. Also, at a time when the Broadway clubs were being harassed by the administration of then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein, nobody in officialdom bothered much with the Sound of Music. In the 1979 mayoral election, of course, Dead Kennedys singer Jello Biafra had challenged Feinstein, who’d become mayor the year before when Dan White murdered Mayor George Moscone in his office, taking down Supervisor Harvey Milk as well.

Along with serious proposals such as banning cars downtown or requiring police to be elected from the precincts they served, Biafra vacuumed leaves in Feinstein’s Pacific Heights neighborhood to mock her publicity stunt of spending a couple of hours with a broom sweeping Tenderloin streets. Biafra came in third behind Feinstein and Quentin Kopp, with 6,591 votes in the general election. Which is not to say the club entirely escaped the attention of authorities.

Drummer Jane Weems recalled walking out of the bar one night and into the glare of police spotlights, shining on a man standing in front of the club with a needle in his arm, poised to inject. Instead of the suspect pleading with police to “Don’t shoot!” this time it was the cops shouting, “Don’t push that plunger!” But, Weems said, he did anyway.

“You saw fucked-up shit all over the place,” she said. “You were a young adult who could be up at night, who could go to shows, etcetera, and you could see the nightlife for the first time and it was crazy.”

“One afternoon, while I was setting up the bar,” Simmans recalled, “two police officers came in and asked me for my ID. I said I needed to go get my boss, and ran down the narrow stairs calling ‘Celso, you gotta come up here now!’ He met me halfway up the staircase and I told him the cops were here and that I was 17. He didn’t bat an eye, and told me very seriously to go downstairs and not come out until he came down to get me. I did as he asked, and, unfortunately, never bartended there again. The Sound of Music was not shut down as a result of my age, and Celso remained a gentleman and a friend."

“Frightwig played our first show there and many times after. It was a great club that welcomed us in all of our freaky flavors, never asked for a demo, just embraced the entire scene and swallowed it whole!” Carmela Thompson, a former bike messenger who still performs around town in a number of bands when she’s not working as a genetic consultant, remembers how at her band Short Dogs Grow’s first-ever gig, at the Sound of Music, they only got to do about three songs before the police shut it down over underage kids in the bar. At their next gig, she found herself working the door, telling underage kids, “If the cops come, just go hide in the bathroom." "It was pretty loose,” she said. Of the band, “I don’t think any of us were 21."

Thompson and Webster both described Ruperto’s haplessness as a businessman. Thompson eventually would insist that there be a doorman hired and adequate supplies of beer for sale before her bands would agree to play. “He’d run out of beer. He’d go to the store and buy beer to sell at the club,” she said.

Hood remembered how Ruperto let teenage artist Kim Setzer do some “really raw” murals of boxers, and now-deceased Toiling Midgets drummer Tim Mooney about seeing a car burning in the back. He saw someone in there, but it was “too hot” to attempt a rescue.

Webster remembers doing battle with the TL’s dope dealers who wanted to ply their trade in the club’s bathrooms. Maybe that was why, as another patron recalled, the women’s room had no locks.

In the basement rooms across the street from the Sound of Music where bands would practice at Turk Street Studios, burglary was a constant problem. Eric Bradner, who led the TL walking tour during the Punk Rock Renaissance program, told of bands outside the Sound of Music being offered their own gear, freshly stolen from the studios across the street, at bargain prices.

Bass player Lizard Aseltine said, “I used to swamp the bar so I could see shows. I loved seeing Tragic Mulatto. I remember Gayle’s green, duct-tape bra. They were fantastic. I liked seeing Eric Rad’s band Sik Klick — an obvious reference and reverence to the Lewd’s Bob Clic. Another great memory was seeing the Contractions. I was a huge fan of Kathy Peck and I loved watching their drummer with her electric drill. There were many a great time.”

Bassist Peck went on to in 1988 cofound H.E.A.R. — Hearing and Education Awareness for Rockers, a nonprofit that battles hearing loss, especially in teens — after her own experiences with hearing loss and tinnitus. The Contractions appear on the only known record from the bar, 1983’s “SF Sound of Music Club Live, Vol. 1” which also included Repeat Offenders, ELF, Arkansaw Man, Boy Trouble, Defectors, Ibbillly Bibbilly, Dogtown, Katherine and Farmers. You can’t even find it on eBay.

Tragic Mulatto, Webster said, “was one of our go-to bands. There were only three of them. When there was a gap in the bookings — and there were many — I’d walk across the street to Turk Street Studios. And if the show was advertised in advance, they could draw a pretty good crowd.”

Eric Rad, whose band Housecoat Project was another mainstay of the scene, died of a heart attack onstage at the Mab. His wake was held at the Sound of Music. He is remembered for wearing long dresses to work in the copy shop in the lobby of the Mills Building, 220 Montgomery, long before Boy George took that style mainstream. Two of the incredible, industrial-looking guitars he designed and built from random metal and plastic parts, with innovative features, are now displayed at the Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, donated by Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top, who bought them.

The Sound of Music was hardly the only locus for punks in the Tenderloin and Civic Center, though. Out at the Civic Center, the Ramones played a free concert in August 1979. At the corner of Eddy and Taylor, the upstairs after-hours 181 Club hosted occasional shows in its bordello atmosphere, where patrons could bring in a bottle and pay $10 for a setup. And there were plenty of punks hanging out on Polk Street and sharing cheap flats. “I remember seeing Faith No More at the Sound of Music, and that it was small and grimy, and later going to 181 after shows to dance with the drag queens,” Michele said.

Images of burning police cars from the White Night riots of May 21, 1979, outside City Hall were featured on the cover of the Dead Kennedys’ first album, “Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables” released later that year — rumor has it that the protest was somber and uneventful until some punks decided to start breaking City Hall windows and torching police cars. Ruperto died in Reno in 1990, reportedly of a heart attack.

According to Coyote, Ruperto, who dressed and lived like a pauper, left half a million in his bank account. Included in the Punk Rock Sewing Circle’s Renaissance week events was a tampon drive, organized with St. Anthony’s. A pair of mannequin legs with fishnet stockings was placed at venue doors, calling attention to the collection of sealed boxes of tampons and pads, or cash for a cause. More than 550 boxes were donated.

The Sound of Music hosted its last show in 1987, Webster, who worked there almost to the end, said. It’s currently vacant and “available,” according to signs posted on its windows. Upstairs is the Helen Hotel. Next door, as ever, is a vacant lot on one side and an auto shop on the other.

Most recently, it was a thrift

shop. And across the street, bands still

practice at Turk Street Studios, although

these days it’s one of 600 spread across

four states owned by a company that

calls itself Franciscan Studios.

The beat goes on.