Emperor Norton might not have approved—he apparently wanted to fine a person $200 for the transgression—but there are some places in the city where it’s safe to say the word Frisco. And one of them, surprisingly, is the Hyde Street Pier on Fisherman’s Wharf.

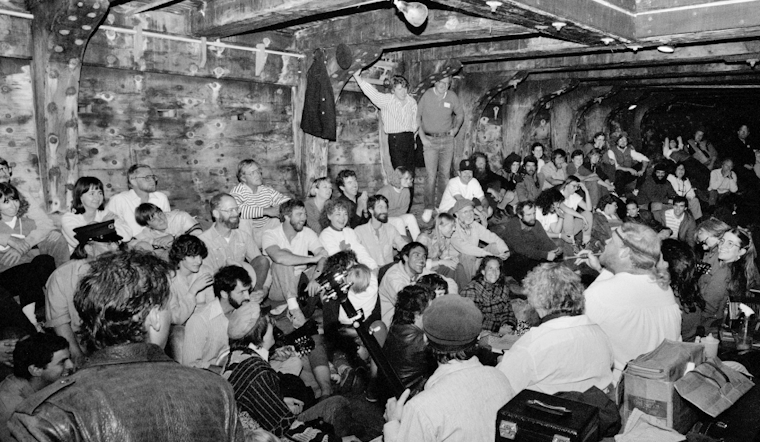

There, dozens of sea chantey enthusiasts gather aboard the gently listing 1890, wooden-hulled, sidewheel paddle steam ferryboat the Eureka on the first Saturday night of every month to sing call-and-response songs from the mid-19th century, considered the Golden Age of sea chanteys.

And there, as you walk up the gangplank any time between 8 p.m. and midnight for the free event, you’re likely to hear lyrics like “If you ever go to Frisco town...” followed by a hearty chorus of “Whiskey, Johnny,” or “In Frisco Bay there were three ships/A long time ago.”

“In the maritime world, we think of Frisco as a term of endearment that was used by sailors around the world,” says Peter Kasin. Since 1992 Kasin has been a park ranger for San Francisco’s Maritime National Historical Park and has been leading the chantey sings since 1996. “It was affectionate—or not, if they were warning about the dangers of the Barbary Coast,” he adds.

Oldies like “What Do We Do with a Drunken Sailor” and “Blow the Man Down” are the tip of the iceberg, so to speak, of a more esoteric collection favored at the sing.

The square-rigger Balclutha off the Hyde Street Pier. Built in 1886, the ship would have had many chanteys sung on board as it sailed between San Francisco, through Cape Horn and on to the rest of the world. (Photo via the National Park Service)

The square-rigger Balclutha off the Hyde Street Pier. Built in 1886, the ship would have had many chanteys sung on board as it sailed between San Francisco, through Cape Horn and on to the rest of the world. (Photo via the National Park Service)

Most chanteys come from this country, the British Isles and the West Indies, and some from France or elsewhere. They’re work songs of the deep-water ships that sailed the seas back then. They are also the net-hauling songs of fishermen in places like the Carolinas, even Japan, and they are songs of oarsmen and cargo handlers.

“The songs were still sung into the early 20th century, on the last of the sailing ships,” says Kasin. In fact, sea chanteys started as early as the 1830s, he explains, when square riggers went out on long sea voyages. But the heyday was around the 1850s, with the larger clipper ships that required more sailors working together. By hand, they had to turn the capstan to weigh anchor, haul on the halyards to raise the sails, pump the bilge and more. Call and response songs helped them coordinate the rhythm of the difficult and monotonous tasks.

The sea chantey, for some aficionados, possesses a lure that goes along with a passion for all things seafaring. Kasin grew up on folk, later rock, blues and jazz, and has for a long time been playing Irish traditional music on the fiddle at the Starry Plough. But it wasn’t until he started working as a ranger that he caught the sea chantey bug and got up the nerve to sing as well as play.

A rendition of the John Kanaka Sea Chanty, about a ship leaving for the "Frisco Bay."

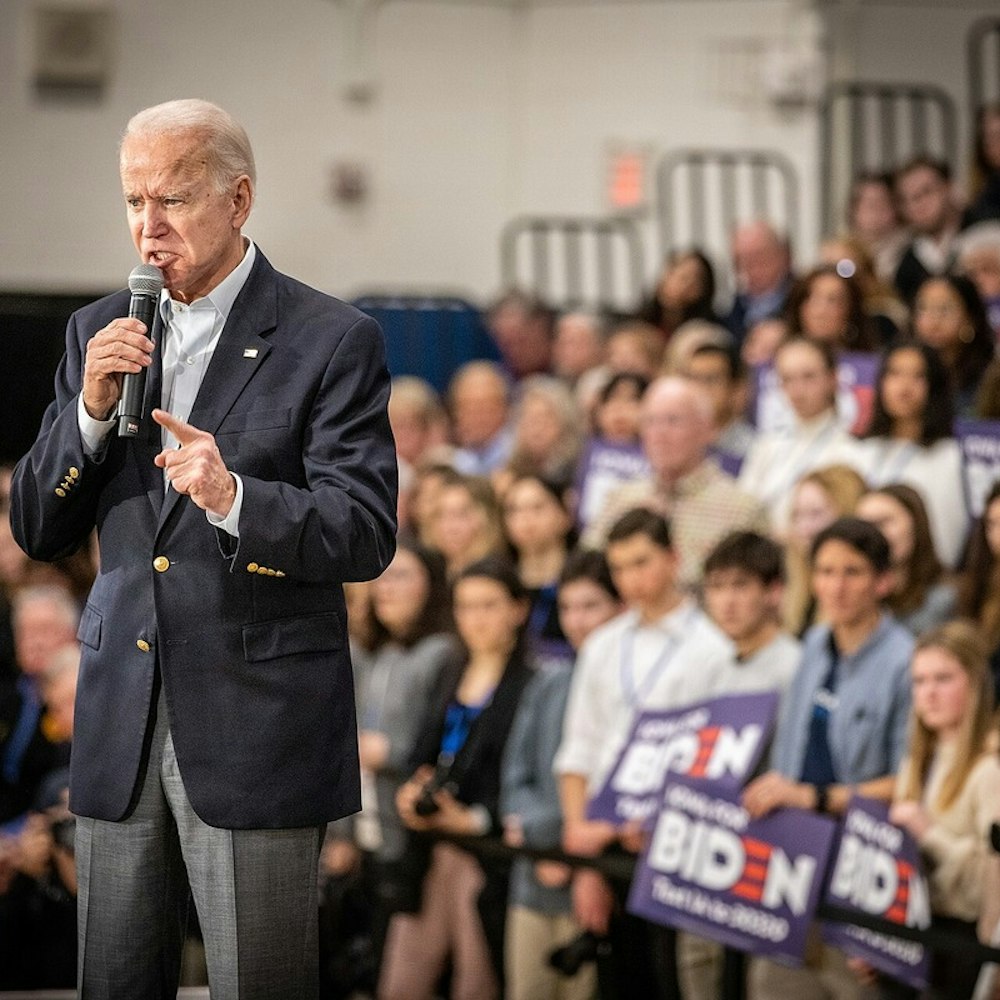

The folks who gather on the Eureka—sometimes as many as several hundred--are mostly locals, plus some tourists; the group has grown since its inception in 1981, when a small group decided to meet after a sea festival concert. Kasin says the San Francisco sessions are the oldest in the country; more recently, chantey sings have cropped up in places like Mystic Seaport, Conn.

These days, participants arrive with lyrics loaded onto their iPads. Anyone can pop up at any time and lead a song, including those with certifiably tin ears —(“Sailors weren’t recruited from opera houses!” Kasin points out). Over time, so many regulars have become familiar with the choruses that the responses are instantaneous and need no instruction from the song leader. The sessions are intergenerational, and Kasin has seen participants grow from kids to adults.

The crowd assembles on folding chairs, with Kasin facing them, usually flanked by a few musicians, such as the achingly sweet-voiced Riggy Rackin, who plays a concertina. All chantey sings begin with “Away Rio,” a reference to a river in Brazil (and pronounced rye-o): (“Sing fare-thee-well my Frisco girl/And we’re bound for the Rio Grande); sung when taking in the anchor, it was thus traditionally the first song sung aboard ship.

So how many sea chanteys are there? No one knows. A lot were lost to history. Luckily a handful of collectors wrote down music and lyrics, and early-20th-century folklorists recorded retired chanteymen for the Library of Congress, according to the Park. Many of those songs have found their way into the monthly chantey sing, picked up by participants through recordings, songbooks and online.

Also in the repertoire are “forebitters,” songs that sailors sung during a two-hour leisure break called “dog watch,” when they’d bring out their accordions, fiddles and flutes; those include drinking songs and other songs of the period. Among the particularly popular songs at the chantey sing, says Kasin, are “Reuben Ranzo” (“Ranzo was a tailor/Ranzo, me boys, Ranzo/Now he is a sailor/Ranzo, me boys, Ranzo”) and “Hard times in Old Virginia,” a cargo-loading chantey: “Oh, in old Virginia/Hard times in old Virginia.”

Many of the chanteys express longing for the girls back home (or praise for the beautiful “Spanish girls I met around Cape Horn”). Others are bleak and dark (“As you wallop around Cape Horn you wish to God you’d never been born”). “It could be a miserable life,” acknowledges Kasin. “Sailors would dream of freedom. The lyrics show us a lot of what was on their minds—universal concepts: fear, courage, longing for a better life. A lot of the themes that come up connect as with emotions as well as with history.”

And, inevitably, some of the lyrics were racist or sexist. Kasin enforces a few rules: no risqué songs until the final hour (11-midnight); and no lyrics that use the n-word. There’s also no liquor allowed on board ship, but at the breaks, everyone troops across the pier to the three-masted, 1886 Balclutha—the site of the original chantey sings, until they got too big for her—for free hot chocolate and cider served up by Alice Watts, who has been working the galley for about 30 years.

By long tradition, every chantey sing ends with “Leave Her, Johnny” (“For the voyage is done and the winds do blow/And it's time for us to leave her), a song for pumping the bilge.

The demographics of the attendees have changed over time, notes Kasin—there’s a greater ethnic mix these days. “Which is great—this is everyone’s music,” he says.

The chantey sing happens on the first Saturday night of every month. For more information call (415) 561-7171 or email [email protected]