Since he moved to San Francisco, Michael Helquist has used his reporting as a tool for social advocacy—particularly when it comes to the Masonic Avenue Streetscape Improvement Project, which will add two bike lanes and a tree-lined median along an accident-prone stretch of Masonic by removing street parking.

As the project gets underway this year, we caught up with Helquist to hear more about its history, as well as his work in San Francisco during the AIDS epidemic and his new book on the most radical woman you’ve never heard of.

The roots of the Masonic project stretch back nearly a decade, before Helquist's involvement, when a handful of concerned residents formed a group called Fix Masonic. The group began discussing ways to calm traffic, meeting with neighbors, local leaders, groups like the SF Bicycle Coalition, and Supervisors.

Helquist remembered an interview with a young dad living on Masonic that captures the fears he and other residents had. While they spoke, the father broke off the conversation to shepherd his two sons directly from the door of his house to the door of his car. “He said, ‘I’m so scared that they will be hit and killed on the sidewalk,’” recalled Helquist, noting that accidents along the street involve not only bicyclists, but pedestrians and drivers as well.

By February of 2008, Fix Masonic had collected 500 signatures calling for a change, and the Board of Supervisors unanimously passed legislation to devise a better street configuration along the Masonic corridor from Geary to Fell.

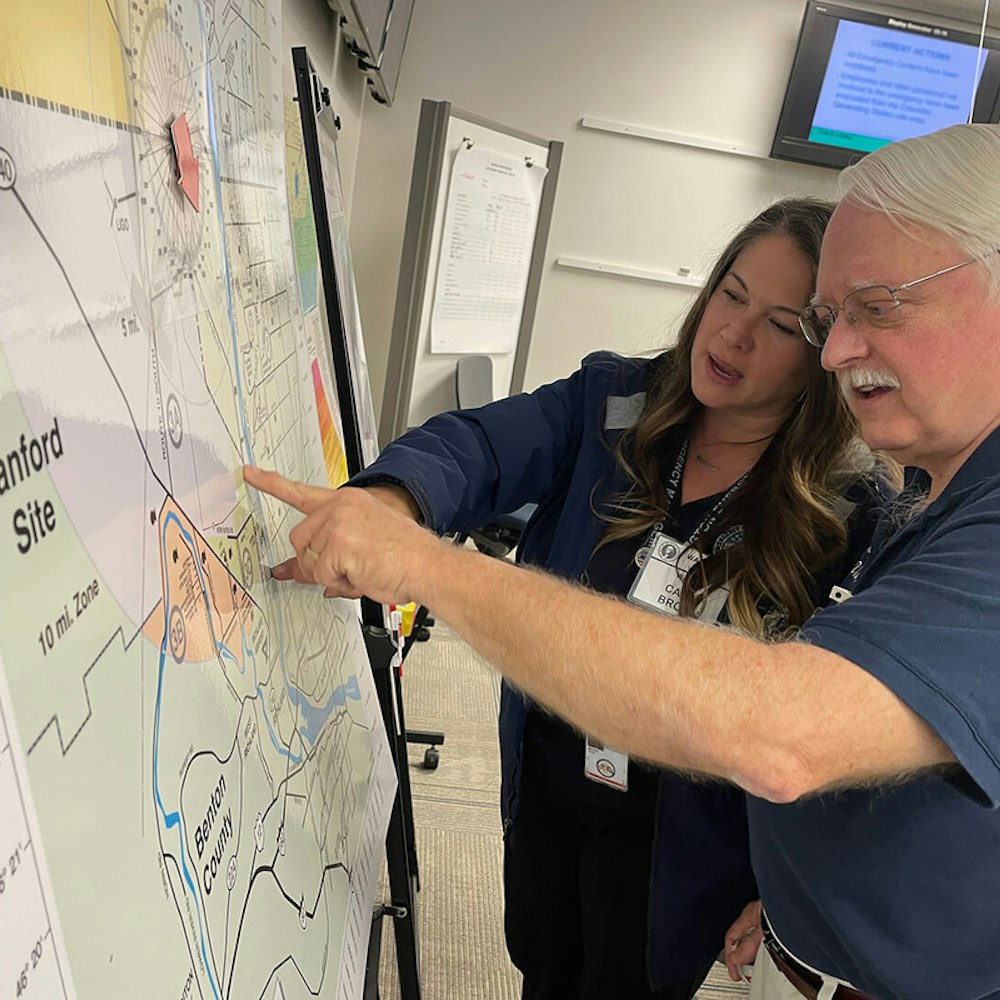

The planned street improvements along Masonic. (Image: SF Public Works)

As Helquist, who served as president of the North of Panhandle Neighborhood Association (NOPNA) for a number of years, got more involved with street safety, he started a blog about biking in the area called Bike NOPA. His goal was to not only discuss what needed changing, but also bring attention to people in community.

“I think it’s important to feature people who are involved, because it makes it more real,” he said. “People go, ‘Oh, my neighbors think this is important enough to get involved.’”

That meant dispelling the stereotype of bicyclists as reckless twentysomething men, by frequently profiling families, women, and dads who get around on two wheels. The increased prevalence of biking has helped change its image and normalized the experience of sharing the road, he said. “When drivers see a mother or father with two small kids in tow on a bike, it’s hard to keep that stereotype.”

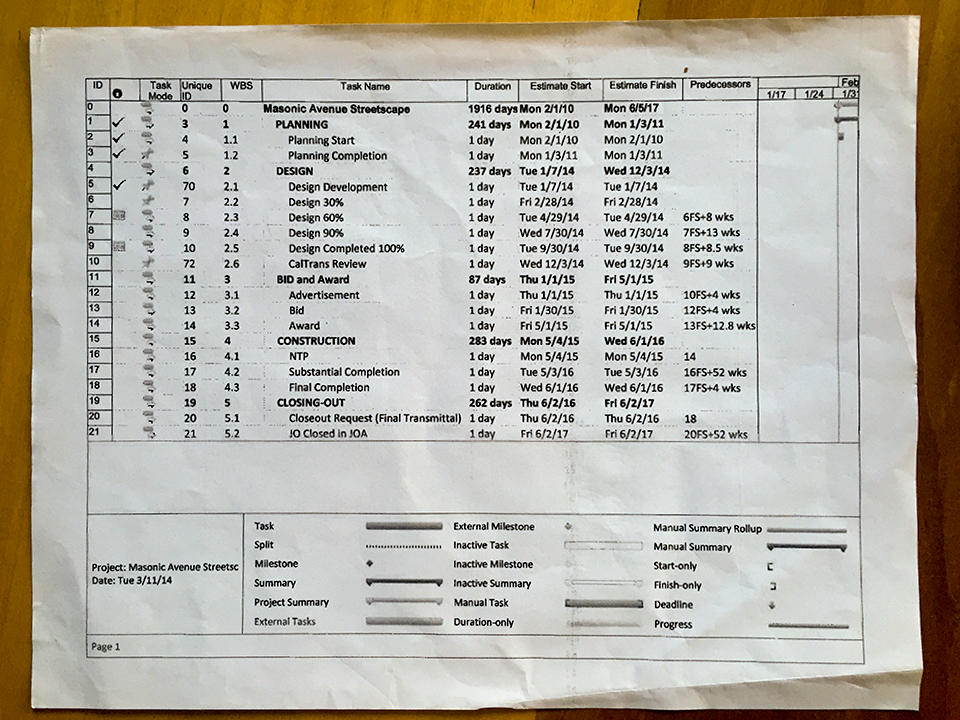

The Masonic Avenue Streetscape Improvement Project schedule in 2014. The project went up for bid in December of 2015, about a year behind schedule.

Once it's finally completed, Helquist believes the Streetscape Project will be an example of successful community planning. But he also warned that it’s a very complex project, more so than many in the city. It's already encountered some delays—and will likely see more in the future.

“It's a full eight blocks of a major thoroughfare. It involves work not only above-ground—the landscaped median, raised bike lane, re-paving, parking removal—but also underground, with upgrading utility and sewer lines and repairs, he said. "Projects like these inevitably encounter design and construction delays,” and it's important for the neighborhood to pay attention so that the city makes staying on track a priority.

Before he turned his writing to street safety, Helquist’s advocacy was largely focused on the AIDS epidemic. The crisis struck soon after he moved to San Francisco, in 1980.

“For AIDS in the early years, there was so much uncertainty of what was involved and what was the risk," he said. "There was so much fear, there was so much discrimination, that sometimes just getting information out in a straightforward, informative way could be social activism in itself.”

Helquist, who had a regular column in The Advocate, eventually went to Washington, D.C. to help direct a global AIDS communication program in developing countries. “Writing has been a lot of my way of focussing the public’s attention to make change.”

In recent years, Helquist has pursued another passion related to social justice: writing a book about the life of Marie Equi, an openly lesbian activist who became one of the West Coast's first woman physicians in the late 1800s. (Though she spent most of her life in Oregon, she studied medicine in SF, returning to the city to provide aid after the 1906 earthquake.)

Marie Equi.

Helquist's book, Marie Equi: Radical Passions and Outlaw Politics, was published by Oregon State University last year. Recently named a 2016 Stonewall Honor Book by the American Library Association, it tells the story of how Equi fought, sometimes literally, for women’s and worker’s rights—she once horsewhipped the school superintendent in the center of The Dalles, Oregon for withholding her girlfriend’s full pay.

In the course of her fiercely independent life, Equi provided birth control and abortions at a time when they were illegal, was one of the first people in a same-sex relationship to adopt a child, and served time in San Quentin for protesting World War I.

“What most people say, other than how did you find out about her, is ‘Why have we never heard of her?’" said Helquist. Once more, he's turned to writing to change that.