This story is the second in a four-part series on Oakland architect Julia Morgan, and the histories of four key buildings she designed. Check out our previous entry in the series, on the Mills College bell tower.

On the morning of April 28th, 1902, the King’s Daughters Home burned down. The hospital for “incurables” on the corner of Oak and 11th St., home to 30 people, was destroyed in a blaze caused by a single oil lamp.

As the San Jose Evening News reported at the time, the fire was started by “aged inmate” William Bray, who knocked over his heating lamp “in an epileptic fit.” Bray and another resident died in the resulting blaze, accelerating the Christian organization's plans to build a new location.

In a statement to the San Francisco Call, the home’s president, Matilda Brown, made an announcement: “We have just paid the first installment on a new site for a home on Thirty-ninth street and New Broadway, where we hope to be able to build a new institution.”

The task of designing that new institution would fall to Julia Morgan, the first female architect to be licensed in California. The project hit close to home for Morgan, whose mother and sister were active volunteers for the women-led King’s Daughters.

Fresh off the success of El Campanil, her groundbreaking reinforced-concrete bell tower at Mills College, Morgan was awarded the contract in 1906.

In early April of that year, she presented her initial design for a single building. Karen McNeill, the former Kevin Starr postdoctoral fellow in California studies at the University of California, describes the design as Second-French-Empire-style: stately, ornate and massive.

But a just few days later, the 1906 earthquake and fires changed everything. The aftermath of the disaster sent labor and material prices through the roof, and Morgan back to the drawing board.

To work on the King's Daughters redesign, Morgan opened a new office in the Merchants Exchange Building in San Francisco. Like El Campanil, it had managed to survive the disaster, and from its top floor, Morgan oversaw a team of young architects.

Julia Donoho, a lawyer-architect who has studied Morgan extensively, says that working for Morgan was “like going to graduate school.”

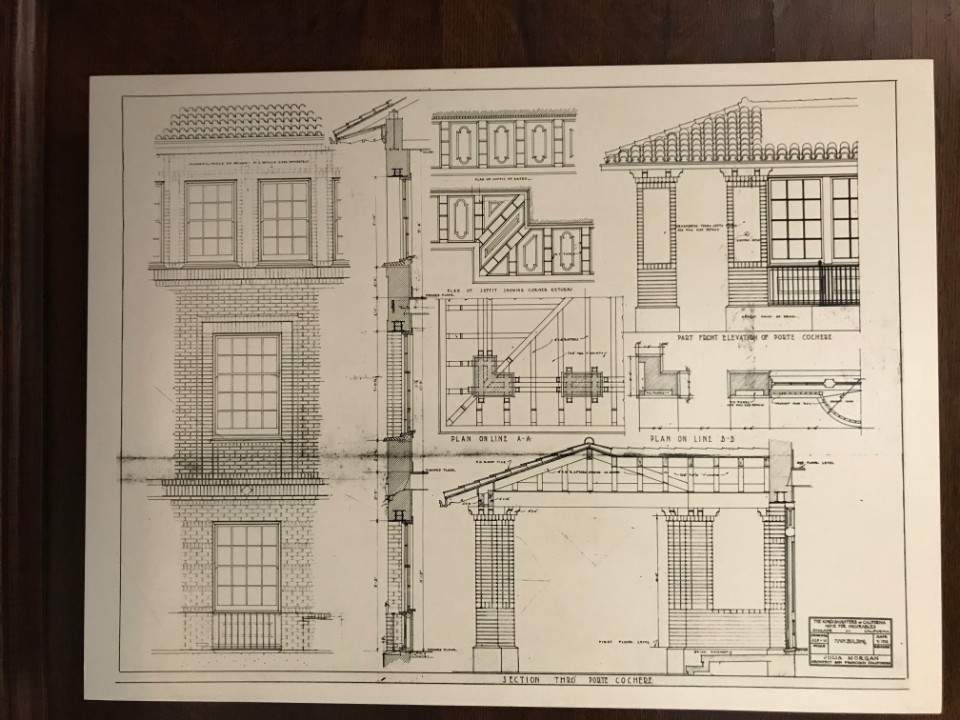

Given the sudden increase in labor and materials costs, even a scaled-down version of Morgan's original design would have been too expensive for King's Daughters. So Morgan devised a development schedule that would match its intermittent cash flow. Between 1908 and 1916, the hospital would rise in stages, starting with the big, symmetrical building that now looms over Broadway.

At the end of each construction push, the King’s Daughters volunteers would hit the pavement: knocking on doors for donations; fundraising through bazaars, teas, and dances; and posing in front of the Morgan-designed steps with signs that displayed their fundraising goals.

In keeping with advances in hospital design, Morgan’s multi-unit layout captured sunlight and natural ventilation and emphasized outdoor space. Compared to Fabiola Hospital and its "massive Victorian approach," said McNeill, the nursing home sported a modern look.

The home served Oakland's chronically ill patients for decades, until it finally shuttered in April 1980. It was registered as an Oakland landmark on November 4, 1980, and in 1981, Kaiser Permanente began moving some of its administrative offices into the buildings.

After an interior remodel of the main building in 1987, the healthcare network’s division for psychiatry and behavioral medicine took up residency, and has remained there ever since.

Despite the intervening decades and the changes in tenants, Morgan’s mark remains. It’s in the copper lanterns, the terra cotta car shelter, and the entrance gate on Broadway, a metal arc that spells the original name: King’s Daughters Home.

According to McNeill, the gate was paid for by Morgan’s mother in honor of Julia's brother, Gardner. Known as "Sam," Gardner was an Oakland firefighter who died in 1913, when his fire engine collided with a street car on East 14th St. (now International Blvd.)

Outside an annex building that used to hold carriages and now holds offices, maintenance worker Ricky Wilkerson steps down from his golf cart and points to more Morgan details — an ornate grill vent, a multicolored ceramic tile, the building’s barn-style doors.

People come to admire them all the time, he says, though he's quick to clarify.

“The outside is all the same," he says. "But the inside is totally different.”