This story is the first in a four-part series on Oakland architect Julia Morgan, and the histories of four key buildings she designed. Look for more entries throughout February.

Every Tuesday morning, Mike McBride, the chief engineer at Mills College, unlocks the doors of El Campanil, the 72-foot campus bell tower. Applying a power drill to a mechanism of gears and cylinders known as a turret clock, he rewinds the cable and weight that spin the clock's hands and ring its bells. The weight descends, another week passes, and McBride repeats the action.

The Spanish Mission-style tower helped make its pioneering architect, Julia Morgan, a world-renowned success. This spring, it will celebrate its 115th anniversary on the Mills campus.

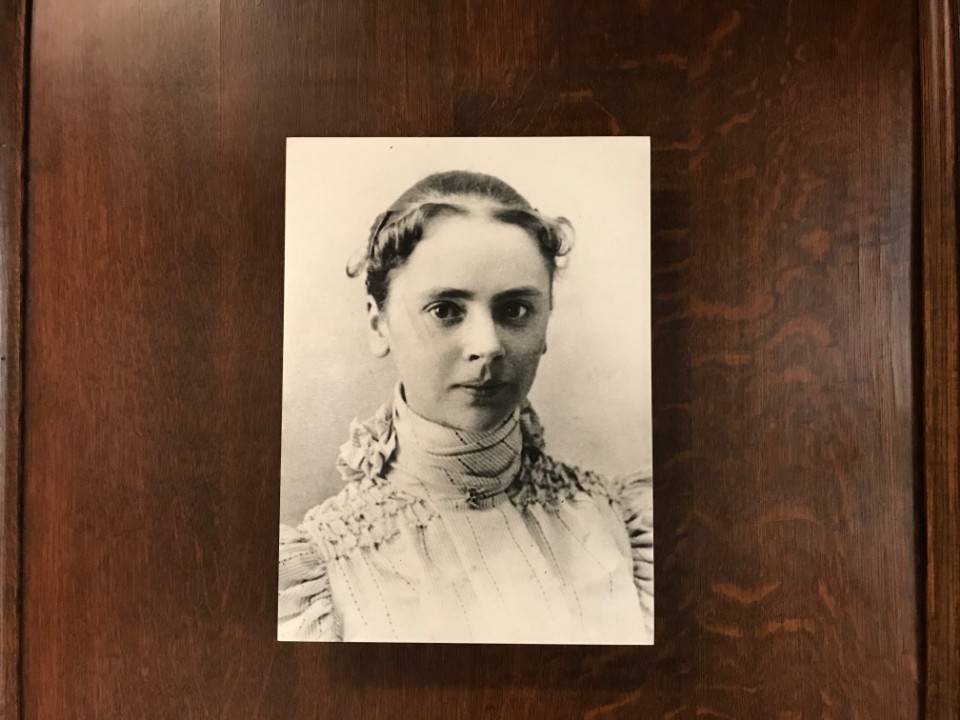

32 years old at the time of El Campanil’s construction, Morgan was a San Francisco native. A graduate of Oakland High and U.C. Berkeley, she was the sole woman in her college class to earn a civil engineering degree, and became the first woman licensed to practice architecture in California.

After returning from her studies at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1902 (where she was also one of the first female graduates), Morgan settled in at her family home in West Oakland. She began to distinguish herself as an architect on the Cal campus, making contributions to the Hearst Mining Building, the Greek Theater and Sather Gate.

That work caught the attention of Susan Mills, co-founder of the women’s college. She and her husband Cyrus, former missionaries, had purchased the former women's seminary in 1865, moving it to Oakland six years later.

But the college's earlier reputation had followed it to its new home. Eager to shake her institution’s “finishing-school past," Susan Mills "needed to make a statement," says historian Karen McNeill, the former Kevin Starr postdoctoral fellow in California studies at the University of California.

So she settled on erecting the first freestanding bell tower on a college campus, with the help of deep-pocketed Francis Marion “Borax” Smith and his wife, Mary. The project would also make use of another lavish gift to the college: 10 large bells, courtesy of local industrialist David Hewes. Cast during the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, they'd been gathering dust in a storage facility ever since.

In 1903, Morgan received the commission, her first major project. (Though some have speculated it was because she charged less than male architects, the evidence doesn't support that theory, McNeill said.)

“Where the Campanil was new and innovative was in using reinforced concrete for a beautiful structure,” said McNeill.

Embedded with a mesh of steel bars, reinforced concrete can now be seen in just about every new housing development in Oakland and San Francisco. But at the turn of the 20th century, it represented a new frontier of construction.

Morgan had studied the material in Paris, where some of its pioneers, François Hennebique and Auguste Perret, were exploring its non-industrial uses. Fascinated by its combination of stability and plasticity, she may have been the first architect in the U.S. to put it towards something other than bridges or piers.

“She knew what she was doing, and there was nobody else who knew what she was doing,” said Julia Donoho, a lawyer and architect who led the campaign to posthumously honor Morgan with the 2014 AIA Gold Medal.

Construction on El Campanil was completed in April 1904, and almost exactly two years later, it was put to the test by the great 1906 earthquake. But amidst the rubble, the bell tower stood tall.

After that, says McNeill, “Morgan was a spectacle.”

“When the Campanil survived the earthquake of 1906 without a crack, that just catapulted Julia Morgan into the highest echelon," she said.

Morgan would go on to construct five more buildings at Mills, along with dozens more in Oakland, hundreds in California (including Hearst Castle in San Simeon) and a smattering around the world, as far as Tokyo.

115 years later, El Campanil still divides the hours. It's so integral to the life of the campus as to almost escape notice — except, that is, when it stops working.

When the 10 bells were sent to Minnesota for repairs in 2003, the atmosphere suddenly changed, said Pat Ernesto, an administrative assistant in the campus facilities office.

“I would get calls from the neighbors, asking 'Why aren’t the clock bells ringing anymore?'" she said.

But they returned in March 2004, and with Mike McBride's help, they've been ringing at the right time ever since.