Alamo Square Park today is a central feature of the neighborhood, if not the city. But before it became a popular destination for locals and tourists alike, it almost got developed over – twice.

Here’s a brief history, as compiled by someone who grew up next door.

Alamo Hill, as the plot of land was originally known, was a stopping point along the Devisadero trail from Mission Dolores to the Presidio. “Devisadero” loosely translates to ‘with a view’ in Spanish, and you can read all about the controversial history of the street name in our article and its comments section from last year.

The name Alamo most likely comes from the fact that there were poplar trees on the land as “alamo” is the Spanish word for the tree.

The Wild West Years

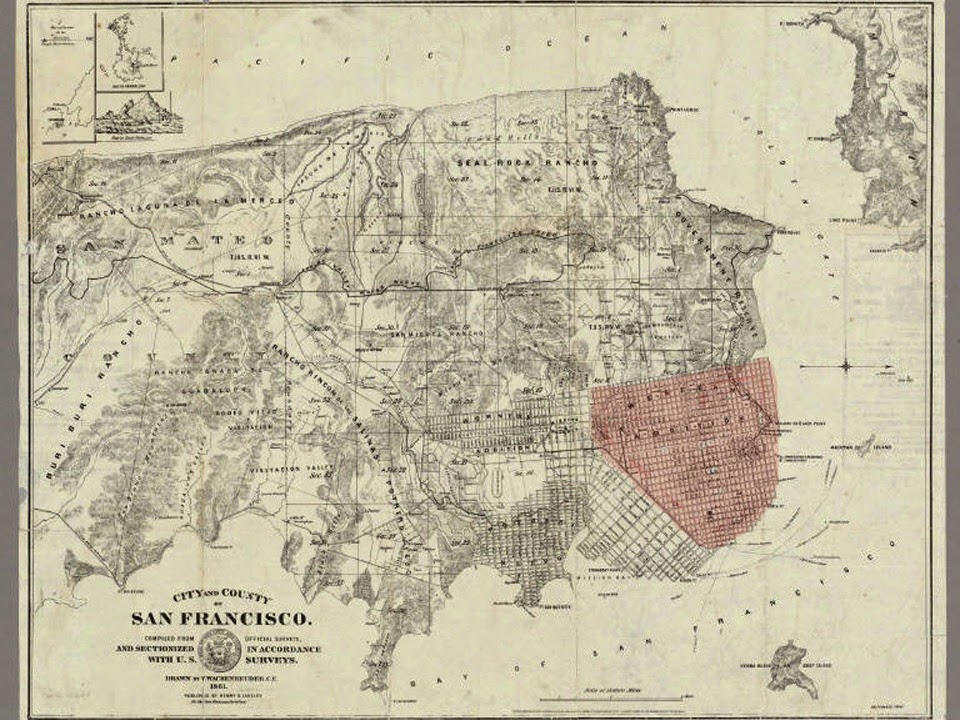

The land started along the path to becoming a park in 1855, when mayor James Van Ness and other city officials began drafting a set of zoning regulations in what would become called the Van Ness Ordinances. The new legislation divided up the land west of Larkin using the grid system seen today – and beginning a long-running series of court cases with existing landowners and squatters to decide who would own what.

The city officially reserved some for public parks, schools, streets and fire lots, and hence, out of the public domain, including what it defined as “Alamo, bounded by Hayes, Steiner, Fulton and Scott streets” in 1857.

Yet most of the city was to the east in these years and the newly-designated park stayed little more than a rocky knoll for years. It became more accessible in the early 1860s, when well-connected city official Thomas Hayes obtained some of the newly-zoned city land down the hill made available with his friend and neighbor, the mayor Van Ness.

In an effort to grow the area, he brought a rail line east from Market Street to what became his namesakes, Hayes Valley and Hayes Street. The line expanded all the way towards Lowell High School (the current CCSF extension campus), located at Masonic between Grove and Hayes.

But Hayes himself ran into financial problems. The line, convenient for access to downtown, eventually passed into the hands of the Market Street Railway, with much of the surrounding real estate still up for grabs.

Early residents used a mixture of political connections, lawsuits against the city and even banditry to take advantage of the situation.

Beginning as just a series of "winding trail,” local journalist Edward Morphy recounts in a series of articles from 1918 how “various enterprising men of wise prevision foresaw the future rise of property values here.”

He tells one story about Jack and Charlie ‘Dutch’ Duane, a pair of infamous quasi-outlaw political figures in early city history, who built a little cottage in the middle of the block bounded by Divisadero, Fulton, Scott and McAllister. The one-story house served as the headquarters from which they hired "desperadoes" in order to defend the “various properties [they] unlawfully preempted from being taken over or built upon by their legitimate owners.”

Charlie Duane in 1880. Photo via John Boessenecker.

Charlie and Jack even shot one of their "objectionable" neighbors downtown during a property dispute. The victim, Colonel W.G. Ross, resided in the block bounded by Divisadero, Mcallister, Broderick and Tyler streets (which is now called Golden Gate). One of the brothers, Charlie, was acquitted and went on to thrive "a squatter and politician for many years, and some idea of what the political morals of the city then were may be inferred from the fact this notorious person [Charlie] was elected chief of the fire department." (In fairness, he was also a bit of a hero in the firefighter role.)

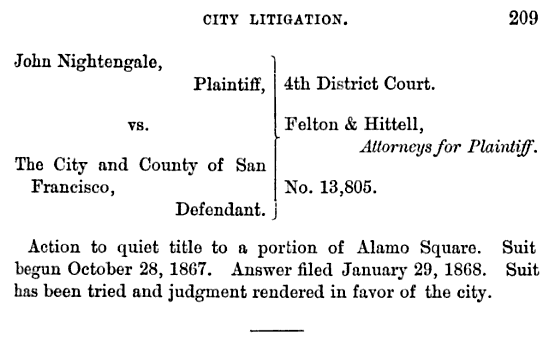

Duane wasn’t the only high-profile figure engaging in aggressive real estate behavior. The City’s rights to the land where Alamo Square stands was heavily contested in court by “several prominent land grabbers and squatters,” local historian Joe Pecora writes in his book, The Storied Houses of Alamo Square.

In addition to the Duane brothers, captain of detectives Isaiah W. Less, City Hall saloon keeper Michael Keeney, and realtor John Nightingale all tried to claim pieces of Alamo Square. (From Resolution 9662, marking the Alamo Square Historic District, 1992. Credits Anne Bloomfield, 1983).

The city managed to finalize the general shape of today’s Western Addition neighborhoods in 1868 via an ordinance that codified many of the zoning and property determinations of the previous years. As Morphy put it in his time, park-goers can still thank the succession of city attorneys who fought these claims and helped guard the public space park.

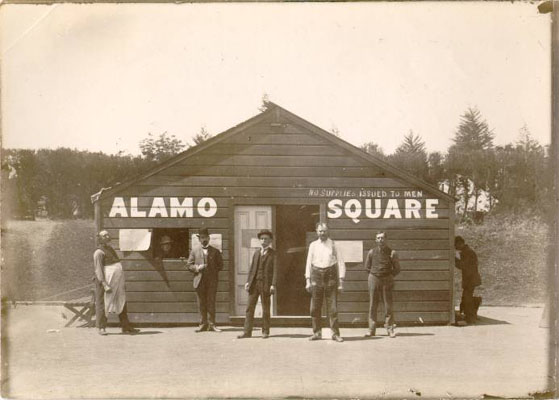

And yet, he writes, the rectangular block stayed, “a primeval forest of rocks at the top of hill" for decades to come.

The City got to work by the end of the century. The park was "graded and tamed" in 1892 at the cost of $25,333 (or around $650,000 in today's dollar). Paths and stairs were laid, and in 1896 the masonry wall was constructed by the California Concrete Company. Many Victorians were built by wealthy business men, doctors and lawyers who commissioned their homes from prominent architects of the time, the most famous of which are Matthew Kavanagh’s ‘Painted Ladies’.

Pecora establishes a detailed history of the area, its buildings and its residents. If you are interested in learning about the builders and first occupants of many of the homes surrounding the park, his book will serve your purpose (and can be bought here).

Alamo Square, like many parks in San Francisco, was used a refugee camp after the earthquake of 1906. An article in the Examiner described it as the park “where people gathered to watch downtown burn in 1906.” (Examiner, Weekend Edition, May 3-4, 2008).

According to one legend recorded by Found SF, the park's place in the earthquake is today remembered in the Bay To Breakers race course..

"[T]he course for the first event coincided with the route earthquake and fire refugees had trekked as they walked up Hayes Street to Alamo Square (just before the race’s 3-mile marker) to the central first-aid station and on to what was the location of the tent cities in Golden Gate Park. That’s still the route of today’s race."

The 20th Century Park

A 1992 Examiner article entitled “It’s a shame what they say about Alamo Square”, spoke of three "transitions" that the park underwent in the century. The article says:

At the turn of the century, its marvelous views of the city, its ornate housing stock and its ready access to downtown made it an elite part of town. But later on in the 1940’s-50’s many of the giant Victorians represented easy pickings for speculators who were hot to carve out the homes into multi-bedroom rooming houses in order to meet demand for apartments.

That's part of the story – by the middle of the century, most of the housing stock near the park was disqualified from mortgages in the racially-charged practice of redlining against urban neighborhoods, and essentially left to fall apart. And as the city planning department under Justin Herman bulldozed the vibrant Fillmore neighborhood to the north in a fraught effort at redevelopment in the 50s and 60s, residents from the predominantly black neighborhood moved south.

In the words of the Alamo Square Neighborhood Association, many of these converted multi-bedroom houses were "illegal and substandard" and “soon became halfway houses, drug rehab centers, or boarding houses for hippies”.

Safety in the park became a "serious issue", according to Jeanne Alexander, of the San Francisco Neighborhood Parks Council. Neighbors Kris and Owen O’Donnell, who moved to Alamo Square in the 70s, told me about when they moved across the street from the park. They let their son go play in the park, and said he’d get robbed every so often and come home beat up. Another neighbor, and life-long resident Aaron Vaughn said: “The park used to be a crazy place – people overdosing, needles everywhere, and I don’t even want to say what was going on behind the bushes.”

ASNA evolved in this complicated environment with the common goal of preservation.

Its creation mirrors, in a certain sense, that of the Haight Ashbury Neighborhood Council and other groups in the neighborhoods movement of the era. Whereas HANC was formed in order to oppose the Panhandle Freeway, ASNA began as a reaction to an early 60s city plan to “slice off the crest of the hill, level it for playing fields and construct a large field house”.

The city was apparently trying to create an adjacent facility for the Alamo Square High School (today the Ida B. Wells High School). But the plan, formalized as a ballot measure, was defeated by the local residents with support from Mayor Joseph Alioto and much of city media.

ASNA went to work on other issues. It got police presence increased in the 70s and 80s, and in a major win for preservation (and tourism) obtained the Alamo Square Historic District title in 1984. In the ensuing decades, ASNA and other neighbors focused efforts on campaigning for money to improve the park grounds and facilities.

Today, the park has received over a million dollars allocated to it by the Rec and Parks’ Capital Improvement plan, with the support of ASNA and other neighbors. This has helped fund the new children’s playground, picnic tables, benches, lights, ADA pathway at Hayes and Steiner, and plastic bag dispensers for dog waste. New restrooms are also on the way. ASNA itself subsidized the $36,000 wrought-iron fence which now surrounds the children’s playground. More recently (and controversially) neighbors lobbied to bring legislation banning tour buses from circling the park.

The park stands today having absorbed 150 years of turbulent city history, as an iconic destination for tourists and locals alike looking for a peaceful place to admire the views.