When 245 Hyde St. opened as a recording studio in 1969, the intersection of Hyde and Eddy was much the same now as it was then: bustling foot traffic, hustlers, and homeless people outside. It takes a moment to acclimate to Hyde Street Studios when you first walk in from the street. It’s a lot calmer.

On this day, there’s a faint smell of weed and the warble of a hip-hop beat emanating from the entrance of Studio A, where Fillmore native Rappin’ 4-Tay is in the booth working on a new record.

4-Tay is just one of a host of recognizable names that have recorded at Hyde Street Studios. Tupac Shakur recorded his debut album, 2Pacalypse Now, here in 1990. It was recently certified gold; the studio is awaiting the delivery of a gold record to hang on the wall.

Before he became a hip-hop legend, ‘Pac was an unofficial member of Digital Underground, the funk-heavy hip-hop group that recorded their debut record here in 1989. Sex Packets, a highly regarded concept album to this day, went platinum. So did Green Day’s second major label release, Insomniac; the band has made several appearances at Hyde Street Studios since recording it there in the mid-1990s.

“If 14-year-old me had known that I’d meet Green Day, he’d pass out,” says Jack Kertzman, a station manager and engineer. He started out at Hyde Street Studios four years ago as an intern. “The history drew me to the studio, the big records recorded here. That, and the preservation of gear from so many different eras of music. It’s a place that’s been making records for 45 years; instead of getting rid of old gear, they’ve maintained it.”

The space has continuously operated as a studio since April 27th, 1969, when it opened as Wally Heider Recording. Heider, a recording engineer for CBS, transformed an old 20th Century Fox soundstage and studio into a place where influential Bay Area bands could record their music. Prior to that, they had to travel to New York or Los Angeles to work in top-notch facilities.

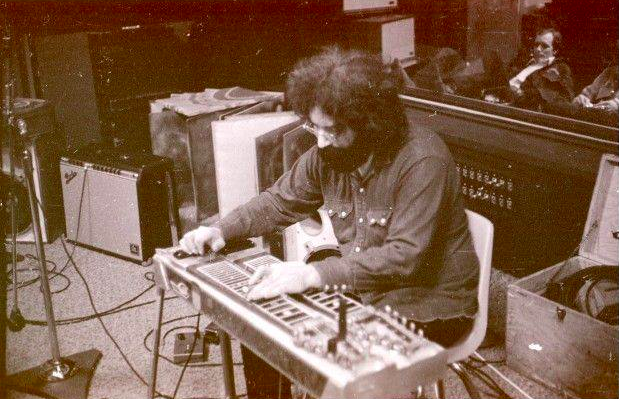

Jefferson Airplane booked studio time before the studio was even completed, and things stayed busy from there. Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young are said to have spent some 800 hours here recording 1969's Déjà Vu. Jerry Garcia played steel guitar on that record, returning with the Grateful Dead to record American Beauty in 1970.

Jerry Garcia recording in Studio C in 1970. (Photo: Stephen Barngard/Courtesy of Hyde Street Studios)

Jerry Garcia recording in Studio C in 1970. (Photo: Stephen Barngard/Courtesy of Hyde Street Studios)

That same year, during Santana’s Abraxas recording sessions, a legendary jam session took place when Eric Clapton stopped by with Derek and the Dominoes. “The story goes that Santana had just wrapped up their session," Kertzman says. “Clapton steps in and jams with them, just playing the blues into the early morning.”

The studio was a hangout and workplace for the likes of Janis Joplin and Mama Cass. Van Morrison recorded Tupelo Honey here; Herbie Hancock, Head Hunters. (Those interested in learning more should pay a visit to the Tenderloin Museum, which boasts an impressive collection of Wally Heider Recording memorabilia.)

The stories that accompany the recording of these massively impactful albums are colorful and a little strange. “There’s one about [Grateful Dead drummer] Mickey Hart booking Studio D for several eight-hour days,” Kertzman says. “He goes in and spends five hours setting up this percussion ensemble. It took him forever to get the tones dialed in, so he only did three hours of actual work on day one. He comes in the next day only to find that everything has been taken down, and he has to do it all over again. Hart was furious, but Heider had him on a technicality: Hart had booked eight hours, not ten, which would have qualified him for a studio lockout. So Hart hires a Hell’s Angel to stand by the door overnight to guard his set-up with a sword."

While the scene at Heider Recording changed by the mid-1970s, it continued to lure an impressive array of talent, including Wings, Tom Waits, The Ohio Players, Weather Report, and Funkadelic. In 1980, Heider sold the studio to Michael Ward and his partners, who changed its name to Hyde Street Studios. The 1980s and 1990s ushered in punk and hip-hop artists like The Dead Kennedys, Tupac, and Michael Franti and Spearhead.

In the years since purchasing the studio, Ward has kept much of it the same. The kitchen is frozen in time, sporting the same olive color scheme and major appliances as it did in 1969.

Currently, there are two recording studios open: Studio A and Studio D. The other rooms are leased to independent producers, recording beats or doing sound for films or commercials. One tenant is building music apps and synthesizers.

“Everything is music-focused here, and there’s a sense of community,” Kertzman explains. “I’ll run into someone in the hallway and nerd out about microphones for an hour. It adds a lot to the experience you get in the building.”

Studio A.

Studio A.

For most musicians, their time at Hyde Street Studios starts with a tour. “I get people to come in and see what we’re all about as much as I can. People appreciate that,” Kertzman says. “Then we put a plan together and talk about process.”

Once the band is in the studio, the recording process usually takes about 10 days to complete. Independent artists, and even those with label support, don’t have the luxury of letting things unfold gradually while they’re on the clock.

“It’s efficient, but it’s the norm right now,” Kertzman explains. “Gone are the days of two-month lockouts, because Columbia Records isn’t investing in that unless you’re Justin Bieber—and that’ll be in an L.A. studio with six lounges and a sauna.”

With limited time to record, Kertzman pushes bands to prepare in advance. “I suggest they play to a metronome as a band, and suggest they record themselves, even on an iPhone, so they know what they sound like,” Kertzman says. “It sucks to have someone come in the studio, and the bass player is asking the guitarist, ‘Have you always been playing it that way?’"

Smaller budgets also mean fewer people working in the studio on an album. An engineer and an assistant (usually an intern) are always present, but producers are rare. “In a traditional setup, they’re the ones making creative decisions, saying stuff like ‘Okay, gimme a take with more energy,’ or ‘Let’s drop the piano out in this section,’” says Kertzman. With no producer in the room, it’s up to the engineer to provide input when it’s called for.

Nathan Winter, a Hyde Street Studios audio engineer, working with Ryan Tedder of OneRepublic.

Nathan Winter, a Hyde Street Studios audio engineer, working with Ryan Tedder of OneRepublic.

Given how valuable studio time is, the perception that bands spend a lot of time hanging out in the studio while the creative process runs its course isn’t particularly accurate—but it still happens from time to time. “There’s some party sessions,” Kertzman says. “Those aren’t the most fruitful. You don’t get the best shit done if you’re not buckling down.”

Kertzman says he's not there to be anyone’s chaperone. “They can use their studio time any way they want, but I want to make sure they get what they want out of their time,” Kertzman says. “Sometimes a great record isn’t as important as getting creative and having a good time. The creative sessions, when you have time to layer on a bunch of instruments that you probably won’t use, but you want to see how it sounds? Those are really fun records to make.”

As in any business, keeping the customer happy is paramount, and with a clientele as diverse as Hyde Street’s, that requires a lot of flexibility. One easier visitor: Kid Cudi, who booked and paid but never showed up. (Kertzman suspects it was a contingency plan while Cudi was in town for a performance.)

Some, like, Nick Waterhouse, use the studio's vintage equipment as a chance to go back in time. “[Waterhouse] and his producer Mike McHugh went full 1965 with it in Studio D,” Kertzman says. “Every musician in the same room, drums bleeding into organ mics. All the gear is from that era, nothing newer than 1970, and they were recording to tape. The sound, man, you’d swear it came out of 1965.”

Kertzman revels in the opportunity to work with vintage tape. “For me, it’s cool, because all of a sudden, I’m not looking at a screen like I am during digital recording sessions,” he says. “I’m just using my ears.”

A resurgence of interest in analog recording equipment and has served the studio well in a shifting industry. Hyde Street Studios recently completed a major restoration of their Neve 8038 analogue recording console from 1970, a meticulous process that required an investment of nearly $100,000.

“Changes ushered in by technology and the Internet knocked out a lot of those big, multi-room studios, but we’ve made it,” Kertzman says, crediting smart investments made by Ward. “The gear he’s purchased is timeless: the mic collection, the console. He hasn’t skimped on anything. If he’s going to invest in a piece of gear, it’s going to be relevant in 30 years, and that will keep us relevant, too.”