You may have noticed a curious feature in Lafayette Park. Rising up on Gough Street between Clay and Sacramento is a stately six-story Beaux-Arts condominium building. Constructed in 1914, the story of how this private building came to be inside a public park is one of San Francisco’s legendary tales.

A historic resources evaluation of Lafayette Park commissioned by the San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department in 2011 sheds light on this unique circumstance. The building is a remnant of a pitched 19th century legal dispute between the City of San Francisco and a former city attorney, Samuel W. Holladay.

Through an act of Congress, the property that eventually became Lafayette Park was conveyed to the city in 1864 by the U.S. Government, but there was a question as to whether the land had been officially designated as a park by the city. Holliday claimed he owned what is now the eastern half of the park and the city claimed it was in public ownership under a city ordinance. Despite the conflict, Holladay constructed a mansion in 1866 at the top of the hill and called it “Holladay Heights.”

Holladay was able to hold on to his six parcels that bordered Clay Street between Octavia and Gough. The title dispute went on for 70 years, and in the late 1800s, the city slowly began to build the park around the edges of the private estate. Holladay sold one of his parcels that fronted on Gough Street and in 1914 the St. Regis apartment building was constructed. In 1935, the rest of Holladay’s land was finally sold to the city and the following year the mansion was demolished. Holladay's properties were incorporated into the park, but the St. Regis remains as the lone testament to one of the most notorious land title disputes in the city's history.

Because of Lafayette Park's incremental development over several decades, the park we see today reveals two distinct approaches to design. The western half is a formal 19th century arrangement with symmetrical pathways and carefully placed landscaping. The less formal and densely vegetated eastern half reflects improvements that occurred during the Works Progress Administration (WPA) era of the 1930s.

Like many of our older parks, the 11.5 acres are surrounded by a low stone wall, framing the four blocks it covers. Grand staircases rise up from the eastern and southern edges. The park feels larger than it is, with undulating terrain, open fields and hidden nooks. Many tall trees planted as part of the estate, including Eucalyptus, pine, cypress, elm and palm, still stand. There are two playgrounds, an off-leash dog run, picnic areas, "sunbathers slope," restrooms and two tennis courts. And, of course, the stunning views of the city and bay rolling out from its 320-foot peak.

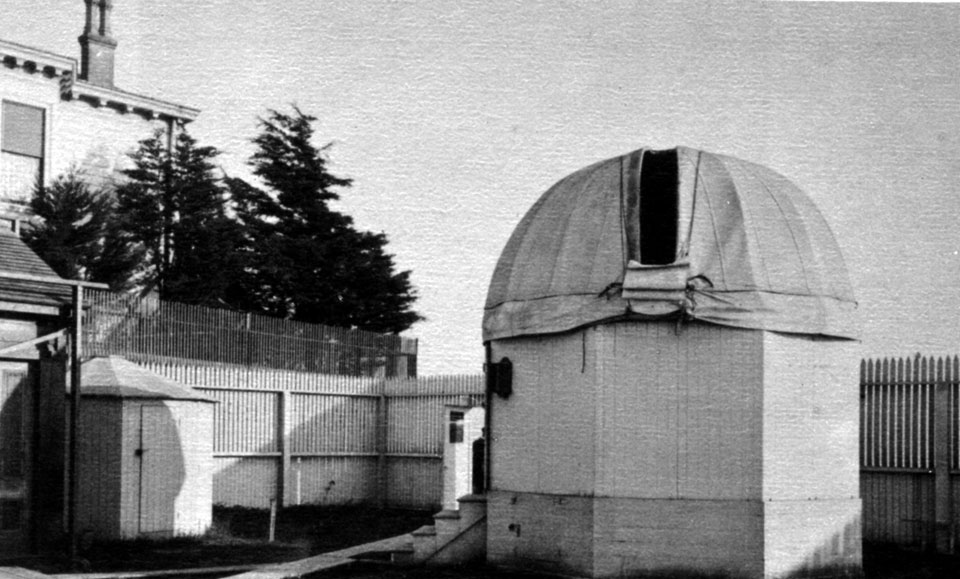

In the late 1800s, the summit served another purpose beyond a sweeping vista for a wealthy landowner. Lafayette Park was the site of the first astronomical observatory on the West Coast. Built in 1879 and maintained by celebrated scientist and scholar George Davidson for over 20 years, the telescope stood next to the Holladay mansion in the middle of the park.

The San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department completed a major renovation of the park in 2013. The improvements were funded through the 2008 Clean and Safe Neighborhood Parks Bond. In the upcoming June 7th election, voters will consider Proposition B, proposing the extension of the fund through 2046.

Friends of Lafayette Park, a nonprofit volunteer organization dedicated to the continued enjoyment and upkeep of the park, hosts "Cleaning & Greening" workdays the first Saturday of each month.

Getting there: Muni's1-California bus runs along Sacramento Street on the park’s south side and the 10-Townsend stops on the north side along Washington Street. The 12-Folsom, 47-Van Ness, 49-Van Ness/Mission stop two blocks away on Van Ness. This park is wheelchair accessible. Parking is on-street only.